Introduction by Polina Ilieva

During the spring semester 2018 the archives team co-taught and facilitated a new History of Health Sciences course, the Anatomy of an Archive. The idea of this course was conceived by the Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine (DAHSM) Assistant Professor, Aimee Medeiros and UCSF Head of Archives & Special Collections, Polina Ilieva. Kelsi Evans, Project Archivist, co-facilitated the discussion sessions and Kelsi, Polina and David Uhlich, Access and Collections Archivist, served as mentors for students’ processing projects throughout the duration of the course.

The goal of this course was to provide an overview of archival science with an emphasis on the theory, methodology, technologies and best practices of archival research, arrangement and description. The archivists put together a list of collections requiring processing and also corresponding to students’ research interests and each student selected one that she/he worked on with her/his mentor to arrange and create a finding aid. During this 10 week long assignment students developed competence researching and describing an archival collection, as well as interpreting the historical record. At the conclusion of this course students wrote a story about their experience and collections they researched for the archives blog. In the next three weeks we will be sharing these posts with you.

This week’s story comes from Antoine S. Johnson, PhD student, UCSF Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine.

Post by Antoine S. Johnson

Historically, racism in America has taken its toll on its victims and UCSF has been no exception—from the black hospital sanitary worker who was restricted to use only the basement bathroom to the qualified medical student denied residency. One month after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., black employees fought back and formed the Black Caucus. The organization not only fought for equal treatment but also advocated for the reaffirmation of black humanity and an increased awareness about the health impact of racism on its sufferers.

The Black Power Movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s consisted of witty slogans that reasserted black humanity. African Americans shouted slogans such as “Black is Beautiful” as a way to convince themselves that black was not as negative and distasteful as society portrayed it. This had important psychological effects. The Black Caucus ensured black staff, faculty, and students joined the movement with similar quotes and passages in its Black Bulletin. In fact, in a March 1971 edition of the Bulletin, the Caucus adopted its own version of the catchphrase, “Black Beauty You Are the Best.” Promoting blackness in a positive way was a unique way for the Caucus to align itself with larger black issues. To show their solidarity, the Caucus advertised speaking engagements and updates on leaders of the Black Power Movement, including Huey P. Newton, Angela Davis, and Kathleen Cleaver.

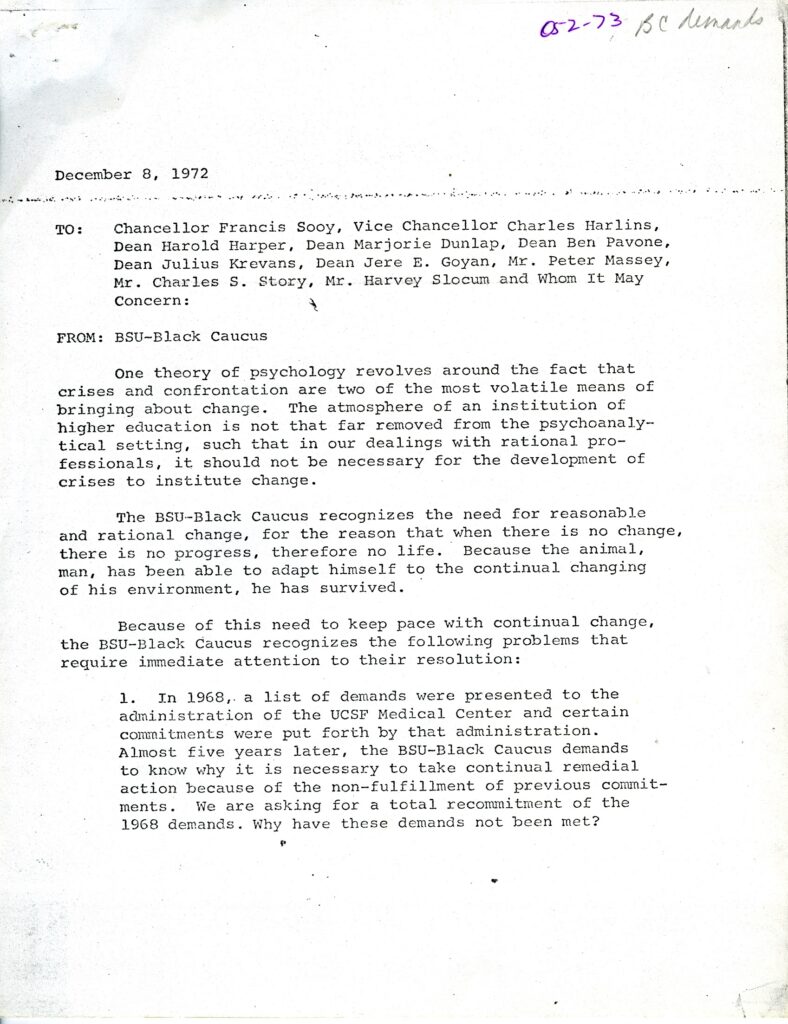

The Black Caucus aimed to demonstrate that racism not only is an injustice but that it can be hazardous to one’s health. Racial discrimination was stressful, it argued. Also, in a 1972 letter to the chancellor, the Caucus posited, “One theory of psychology revolves around the fact that crises and confrontation are two of the most volatile means of bringing about change.”

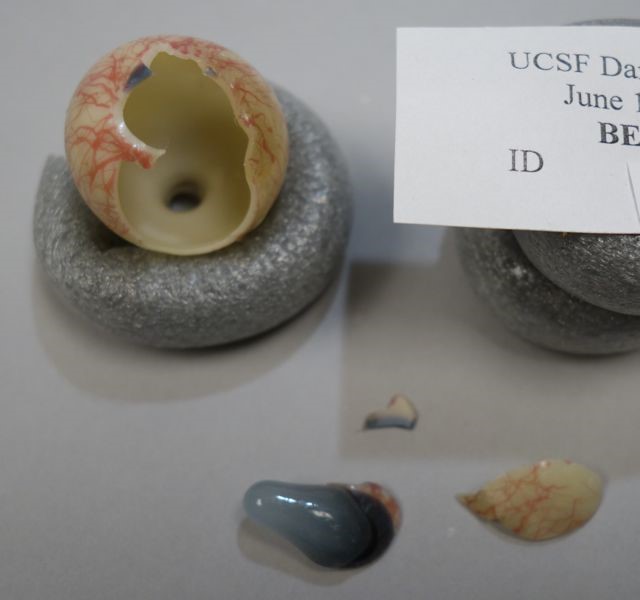

Thus, they refused to allow emotional issues to fall by the wayside, even if the university saw such problems as trivial. The stress could also be a trigger for underlying issues, like G6PD Deficiency. In G6PD, stress is one of the main triggers, resulting in abdominal and back pain, as well as fever and fatigue. The genetic disorder destroys red blood cells prematurely, cutting off oxygen traveling to the lungs, shortening one’s breath, and increasing their heart rate. In the United States, the condition is most common among men of African descent. Aware of this correlation, in 1971, the Caucus screened nearly 600 people on campus for sickle-cell anemia research and G6PD. This campaign to make visible the damage stress brought on by racism could do to black people was extended to the community via the Blackman’s Free Clinic on McAllister Street. Racism knows no boundaries, and the Black Caucus wanted to bring awareness to what should be considered a health concern beyond the walls of UCSF.

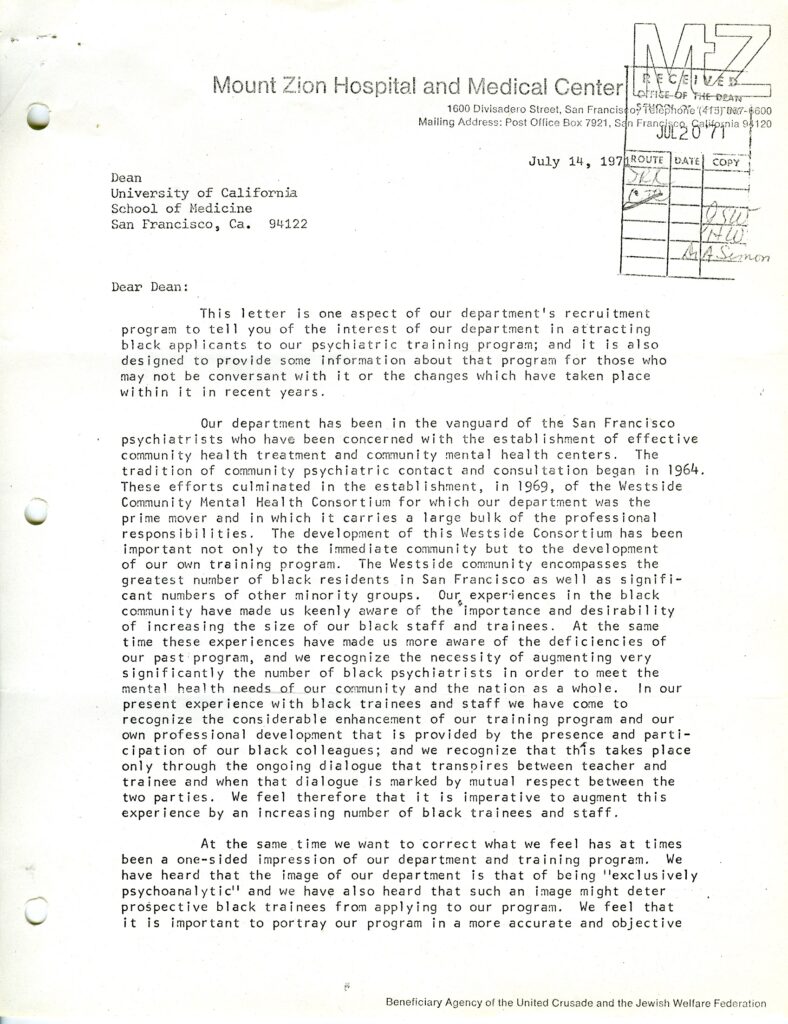

The health of African Americans, in particular mental health, also influenced the Caucus’ demands to diversify UCSF’s clinical faculty. In a statistical document from 1972, the Black Caucus concluded that one in 670 white American citizens became doctors, compared to one in every 5,000 African Americans. The psychiatry department was one of the main divisions in which the Caucus, as well as Edward Weinshel, then-director of the Department of Psychiatry, saw as an imperative to the school’s future. In fact, in a letter dated July 14, 1971, Weinshel pleaded for the university’s psychiatry department to recruit more black applicants. Dr. Charles T. Carman, the Acting Dean, responded in less than two weeks, notifying Weinshel that he sent his letter to the chairman of the psychiatry department, the Assistant Dean for Postdoctoral Affairs, and to Joanne Lewis, then the chairperson of the Black Caucus.

A vested interest in black students would result in more licensed black psychiatrists, a field that both the Caucus and Weinshel saw in dire need of black physicians to assess the mental and physical characteristics of black patients. More importantly, Weinshel foresaw black psychiatrists assisting members of the Westside Community Mental Health Consortium, home of the “greatest number of black residents in San Francisco as well as significant numbers of other minority groups.”

Indeed, “A mind is a terrible thing to waste;” it is also a terrible thing not to protect. UCSF’s Black Caucus was keenly aware of the potential harm endemic racism had on black faculty, staff, and students and surrounding community members. By promoting racial pride and bringing attention to the harmful effects of racism, the Black Caucus spearheaded a movement that highlighted the mental implications of racism, offered solutions, and found allies in their struggle who saw avenues through which the Caucus could get involved within and outside of the university.