This is a guest post by Griffin Burgess, ZSFG Archivist.

The first San Francisco City and County Hospital located on Potrero Avenue was completed in 1872, but it was far from the city center and difficult to get to, which made it less than ideal for emergency cases.

At the time, City Hall housed the police prison, which included an infirmary. This infirmary always had a physician present, so the police and the public became used to using the prison infirmary for emergencies. In 1877, the city formally changed the prison infirmary to the Receiving Hospital and put the Department of Public Health in charge of it.

While the Receiving Hospital provided emergency care to anyone who needed it and played an important role in providing care to the people of San Francisco, the city had no ambulances. To help with this, the police department purchased Chicago-style police patrol wagons, which could carry a stretcher and transport the sick or injured.

In 1893, The World Columbian Exposition and Fair was held in Chicago, Illinois. The new publisher of the San Francisco Chronicle, Michael de Young, attended the fair and saw the working display of the new Studebaker horse-drawn ambulance. When the fair that he organized in San Francisco the next year needed an ambulance, he sent away for a Studebaker ambulance to serve the fair’s hospital.

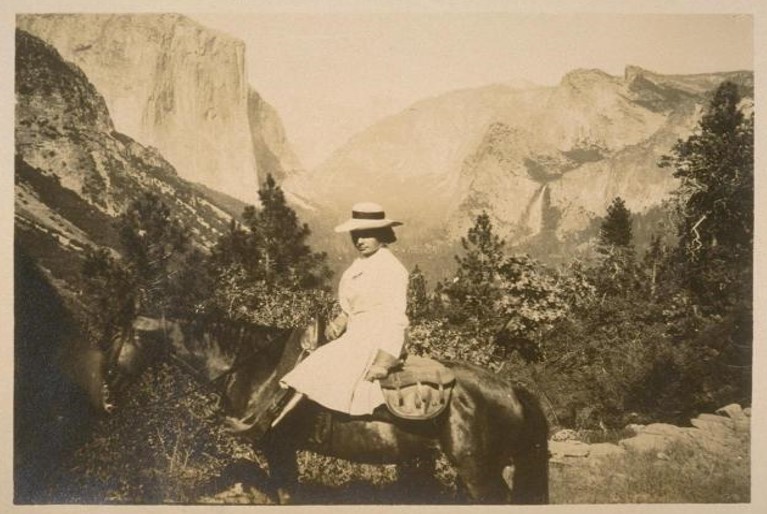

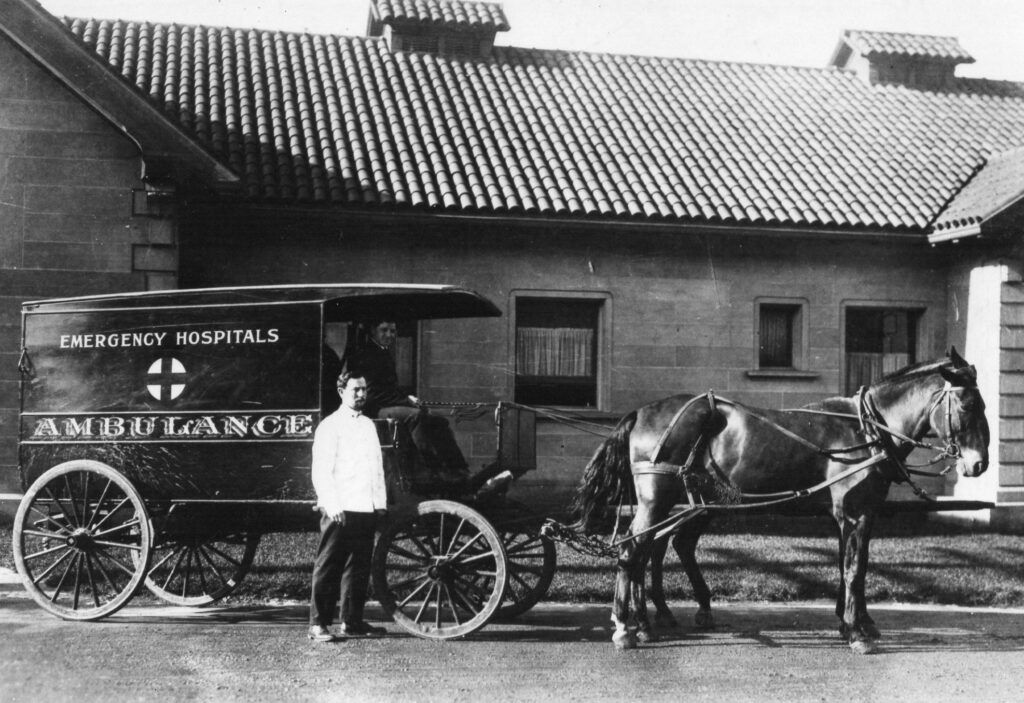

The first San Francisco ambulance in front of Park Emergency Hospital on Stanyan Street, circa 1910.

After the fair, the Studebaker sat in a warehouse until two members of a women’s society group, Theresa Fair Oelrichs and her sister Virginia Fair, bought it and donated it to the Receiving Hospital. It was up to the city to buy the horses, which was done after a bit of politicking.

The director of the Receiving Hospital, Dr. George Somers, insisted that the ambulance be staffed by interns so that medical care could be provided immediately and en route to the hospital, a unique idea at the time. The ambulances were staffed by male nurses until WWII, when former medical corpsmen began working ambulances. Paramedics were introduced in 1973.

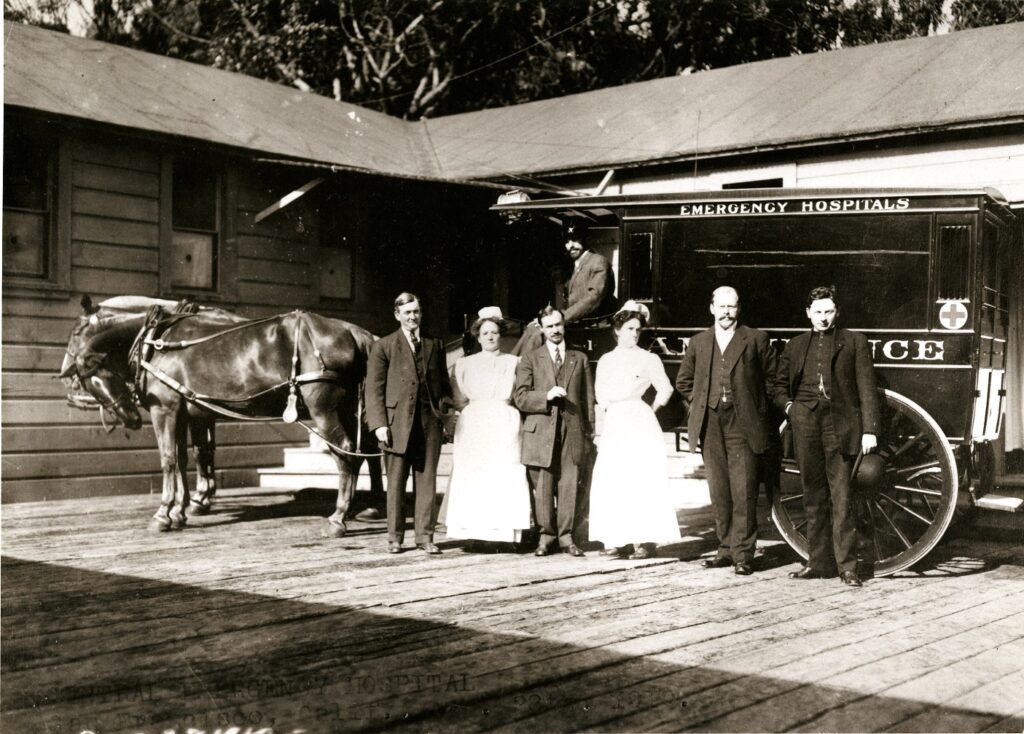

Ambulance in front of the temporary Central Emergency, built after the 1906 earthquake. From left to right: James O’Dea, Annie Andrew, Dr. Fred Zumwalt, Theresa Gile, Charles Bucher RN, William Sullivan, John Thoma (in ambulance).

The 1906 earthquake and fire destroyed much of the city, including City Hall and the Receiving Hospital located in its basement. A new, temporary Central Emergency building in Jefferson Square on Golden Gate Avenue was the first structure completed after the quake.

Ambulance in front of the temporary Mission Emergency building at 23rd St. and Potrero Ave. Circa 1915.

The first Mission Emergency opened in 1909 at 23rd and Potrero. It was later demolished when the red brick San Francisco City and County Hospital was completed and the new Mission Emergency at 22nd and Potrero was opened in 1917.

In 1912, the Emergency Service received its first automobile ambulance. It was stationed at Park Emergency Hospital so that drivers, who until then had only driven horse-drawn ambulances, could learn to operate it on the relatively empty roads of Golden Gate Park.

Not all of the drivers adjusted well to the switch to automobiles, however. “One of the Park Emergency ambulance drivers eventually required transfer to another City department. On his transfer orders, the hospital’s surgeon wrote, ‘… after numerous attempts to convince him to the contrary, this driver still persists in trying to stop the automobile ambulance by pulling back on the steering wheel as hard as he can and screaming at the top of his lungs, ‘Woooh there!’ I feel he is better suited for a department that still uses horses.'” (From Catastrophes, Epidemics and Neglected Diseases by F. William Blaisdell and Moses Grossman, page 134).

The new City and County Hospital was one of the most modern complexes in the country and Mission Emergency soon became the hospital best equipped to care for the severely sick and injured, with updated operating rooms, staff, and equipment. By the end of the 1930s, all of the city’s ambulances were taking emergency cases to Mission Emergency rather than the Central Emergency hospital in Civic Center.