In 2023, the UCSF Archives & Special Collections is embarking on an ambitious oral history project that seeks to elevate the narratives, perspectives, and expertise of historically underrepresented populations in the education and research communities at UCSF. Through engagement with DEIA leaders from each of the four schools (Dentistry, Medicine, Nursing and Pharmacy), we will record their experiences and document efforts to address and remediate inequities in health, health care, and health sciences education. Taking a profile approach, the goals for each interview will be informed by that person’s life history and experiences. At the conclusion of this one-year project we will organize a public event to introduce this new research corpus to the UCSF community.

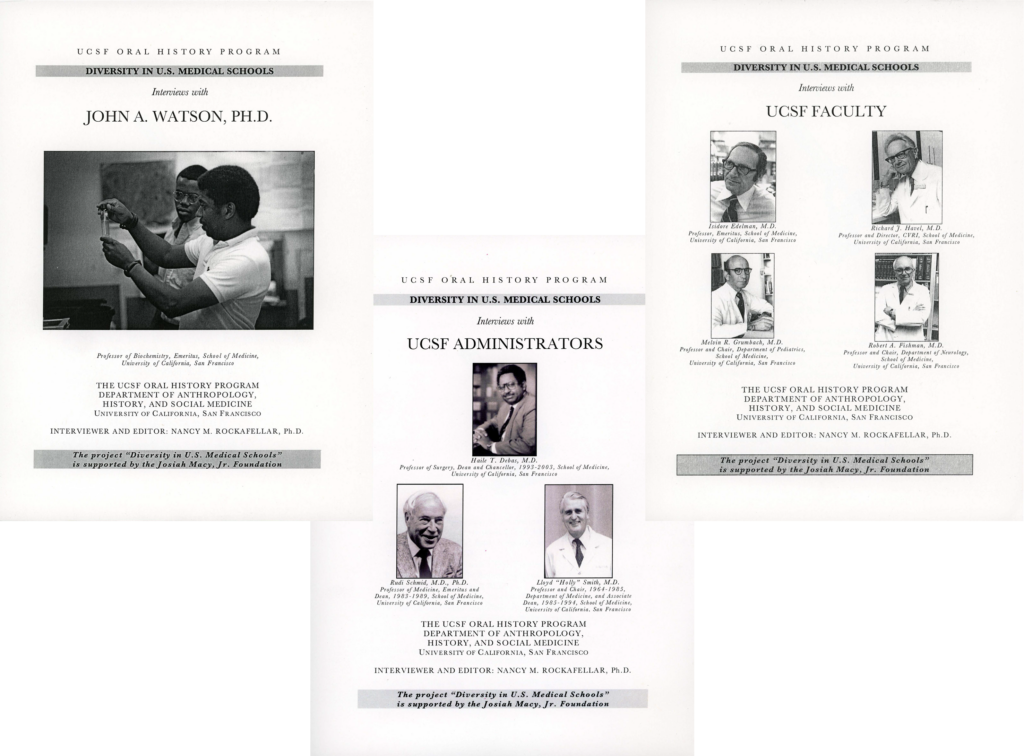

Oral history is one of the many tools Archives & Special Collections uses to document different facets of UCSF’s history. One especially important project, the “Diversity in US Medical Schools” series, focused on policies pursued by UCSF and Stanford University medical schools to increase racial and ethnic diversity from the 1960s to the 2000s. This collection contains interviews with Julius R. Krevans, Philip R. Lee, John A. Watson, John S. Wellington, and others, and documents an important chapter in the university’s work to increase the diversity of medical students at the university. Oral history is a valuable tool because it allows us to document personal stories and remembrances often missed in paper records. As in efforts like the “Diversity in US Medical Schools” series, the DHEHS Oral History Project seeks to understand not just what, for example, DEIA initiatives UCSF has pursued, but why those who led these efforts chose a particular path and how their previous experiences influenced their thinking. Further, we can ask interviewees to reflect on these efforts from the present day and consider the long term impact of their work, including what was successful, and how they might have done things differently.

The first phase of the DHEHS Oral History Project includes forming advisory committees at each of the four schools. The advisory committees’ primary purpose is to develop and prioritize a list of interviewees from their respective schools. Projects of all types benefit from advisory committees, and oral history projects are no different. Especially for projects documenting institutional history, oral history practitioners can come in with little prior knowledge, and must learn as much and they can as quickly as possible. Advisory committees are an ideal group to provide institutional knowledge and expertise efficiently and strategically. For the DHEHS Oral History Project, with support from deans and administrators at all four schools, we’re fortunate to have all the advisory committees established, and all are in various stages of identifying potential interviewees and prioritizing who should be interviewed for this project. Interviewing should commence in the next quarter, and we look forward to hearing the personal experiences of those doing essential work around DEIA and health equity at UCSF.