We’re excited to announce the publication of the UCSF COVID-19 Response Web-Archive. UCSF has historically been a “first responder” to a wide variety of public health emergencies. At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, UCSF archivists recognized that the evolving UCSF response to the situation would contain valuable information about this important, tragic, and devastating historical moment, and that documenting that response as it grew and changed would be a powerful historical record. And we were able to act quickly, because so much of the record is on the web.

Archives and Special Collections has been archiving websites for a long time — our oldest captures date back to 2007, which feels like another epoch in web-time (you can see all of our web-archives here: https://archive-it.org/organizations/986). To archive the web, we use specialized tools to take “captures” or “snapshots” of a certain web-page at a certain time, usually coming back to take a new capture at regular intervals. Because of this technique, web-archives are a valuable way to watch any given website evolve and change, and this documents something like a rapidly-evolving response to a global pandemic very well.

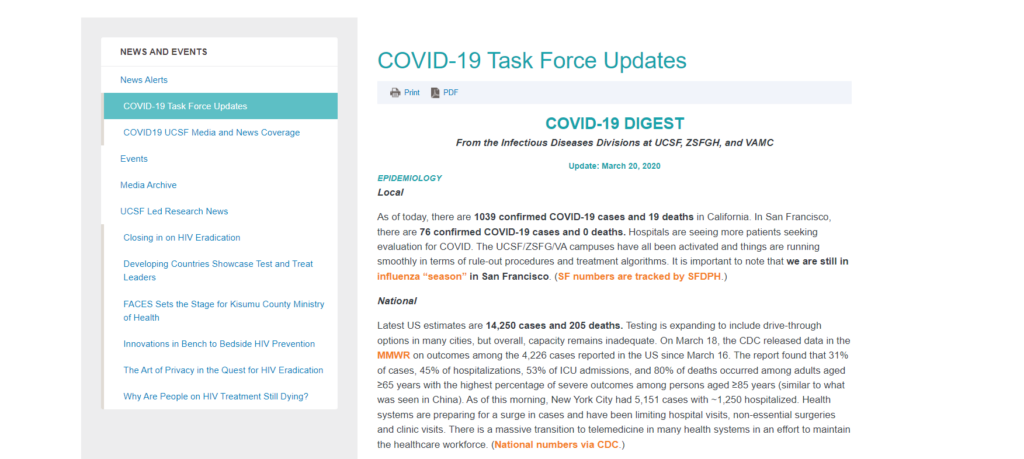

In documenting the UCSF response to COVID-19 however, we had to work much more quickly and in much greater volume than we are used to. As you likely remember, during the height of the early days of the pandemic both the UCSF and the nationwide response was changing daily based on rapidly shifting information. Archives usually captures web-pages every 3 months or every 6 months, but upon embarking on this collection we realized that we needed to begin capturing certain websites every day. Additionally, UCSF has at any given time as many as 1000 different official websites (something with ucsf.edu at the base domain), so knowing which of these contained COVID information and should be captured was difficult. To remedy this problem, archivists set up GoogleAlerts to notify us anytime something was published to a ucsf.edu domain which mentioned certain key words identified as likely COVID-related.

And this was only the official UCSF websites. We also wanted to document outside coverage of UCSF activities, things that appeared on news websites, blogs, and occasionally social media (though the latter is persistently difficult to capture — download your Twitter archives people!). We were able to use GoogleAlerts in a similar way to help alert us to these sites, but even more importantly we benefited from the immense assistance of the amazing Anirvan Chatterjee, Director of Data Strategy at the Clinical & Translational Science Institute. Anirvan reached out to us early in the pandemic with a list of sites he had collected that contained documentation of UCSF’s role in the pandemic response, and his human-curated list was immensely helpful. The proliferation of digital information makes human curation and metadata creation increasingly difficult in archival repositories, and having someone like Anirvan who was able to devote the time to it (most digital archivist aren’t able to devote such time, if you can believe it!) really improved the collection.

This collection is also important because it can be both accessed by a human browsing and by a computer doing computational research. We plan to use these materials to expand our work in digital health humanities as well as collections as data as our newest colleague Kathryn Stine gets underway in her role coordinating these programs. Have a question about the COVID-19 web-archive collection? Want to use it in a computational project? Just love it? Get in touch!