This is a guest post by Cristina Nigro, UCSF History of Health Sciences graduate student.

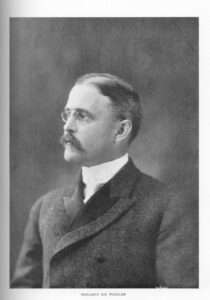

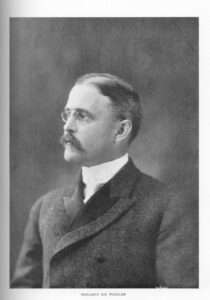

Benjamin Ide Wheeler. Photograph Collection, Portraits.

In his Annual Report of the President of the University to the then-Governor of the State of California, UC President Benjamin Wheeler outlined the part of the university in the Great War:

On February 13, 1917, in view of the increasing probability of the United States entering the European War, the Board of Regents, at the instance of the President of the University, formally offered to the National Government the entire resources of the University for use in meeting whatever needs should arise in prosecuting the war.

The American Red Cross and the Department of Medicine at the University of California Medical School were quick to respond to President Wheeler’s February 1917 call to action. In March, they began organizing plans for Base Hospital #30. According to Wheeler:

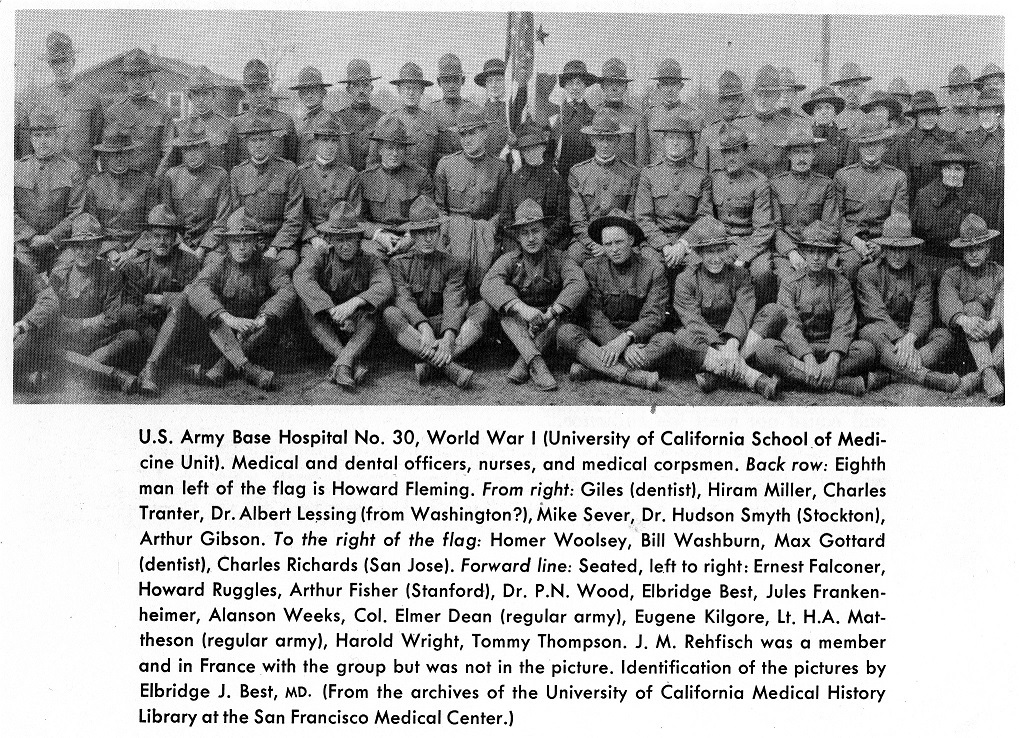

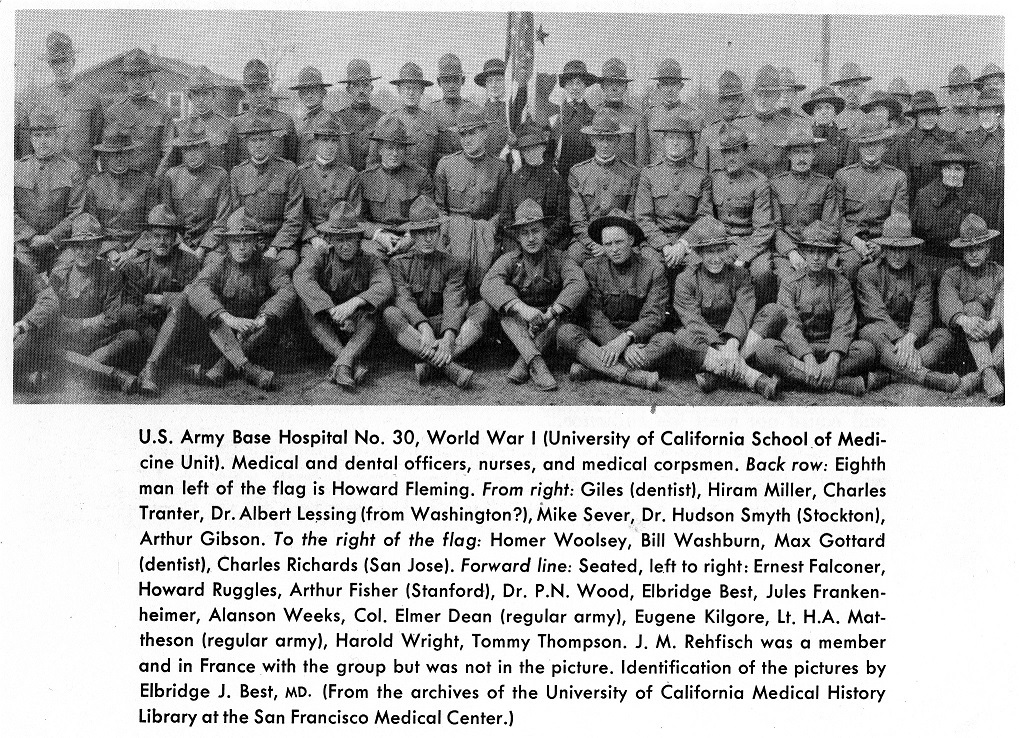

The Medical School has furnished the equipment and many of the members of Hospital Unit 30, under Dr. Kilgore. Of the 25 physicians, 23 are from our Medical School, 13 of them graduates. There are also 10 enlisted men among our medical students. Eight of the 65 nurses are from the University Hospital.

In June, the Base Hospital #30 Unit marched up Market Street as part of the Liberty Loan Parade. But the orders for mobilization to Fort Mason did not come until late November, and the unit had to spend the next three months outfitting and equipping the hospital.

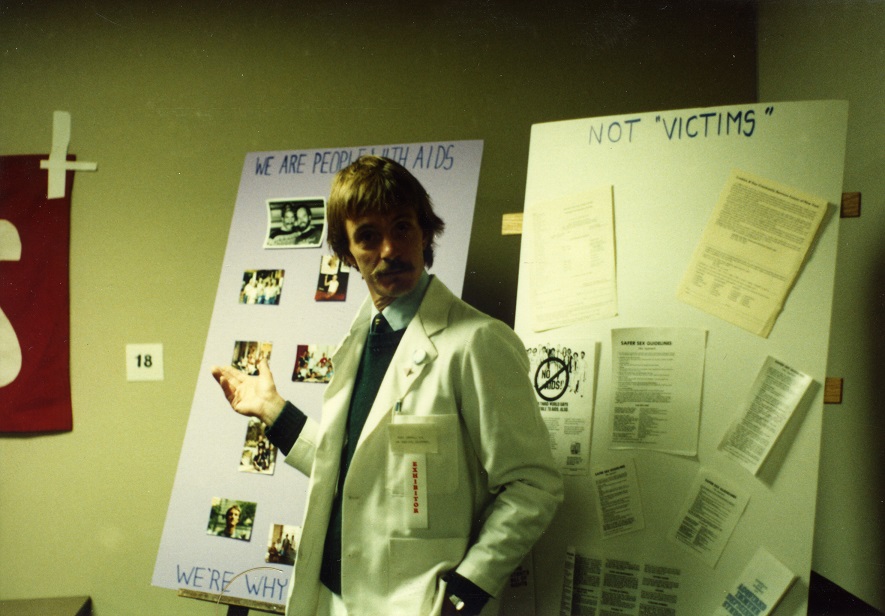

Nurses and soldiers, World War I, circa 1917. From the H.M. Fishbon Memorial Library, UCSF Medical Center at Mount Zion.

The nurses of Base Hospital #30 left Fort Mason on December 26, 1917, arriving in New York Harbor on January 1, 1918. On January 25 the nurses were split up and sent to various Atlantic Coast camps. Eager to be deployed, Acting Chief Nurse Arabella A. Lombard recalled:

The camps were all in sore need of nurses at that time, and after the first huge disappointment at not being able to go directly to France, each one felt glad to be able to do some work in her own country, and in many, if not all instances, much valuable experience was gained from the nursing on this side.

The men of Base Hospital #30 left aboard the S.S. North Pacific on March 3, 1918. After a brief sojourn in New York, the entire unit set sail for Brest, France aboard the USS Leviathan. Following a forty-six hour train ride from Brest, they arrived in Royat, France on May 10, 1918.

Nurses of Base Hospital No. 30, 1918-01. University publications, The Thirtieth.

The first trainload of patients—half British and half American—arrived in Royat on June 12, 1918. Lieutenant-Colonel Eugene S. Kilgore, M.C. remembered feeling unprepared for that first trainload. Of the 369 patients, two thirds of them went to the surgical ward. The second train arrived on June 18, 1918. Kilgore recounted:

We were somewhat, though not much, better prepared for the second trainload of 461 cases from the Chateau Thierry fight. The train commander stated that this was the worst trainload he had ever seen. There were dozens of cases of terrible skin, lung and eye poisoning from mustard gas, and the staff worked night and day trying to keep up with the work of dressing the enormous burns.

Of the 461 new patients, 278 had to be carried in on stretchers.

U.S. Army Base Hospital No. 30, World War I, circa 1917. University publications, The Thirtieth.

Fifteen more trains would arrive at Royat by November 13, 1918, amounting to 4,827 casualties. In the five months between June and November 1918, Base Hospital #30 treated 7,562 patients and grappled with typhoid fever and “a very serious epidemic of respiratory disease.” A train arriving on September 22, 1918 brought 232 men suffering from acute respiratory infections to the base hospital. By the end of September, thirty to seventy influenza patients were admitted to the hospital daily.

On November 11, 1918 the Allies and Germany signed an armistice, ending the fighting on the Western Front. Beginning on December 6, patients were evacuated from the hospital in waves. Reminiscing about her time at Base Hospital #30, nurse Lombard reflected:

After the first train bearing wounded came in on June 12 until some time after the armistice was signed we were very busy most of the time, with only an occasional lull in the work. At times it seemed almost like a night and day proposition. The wounded and sick were wonderfully courageous and our only regret was that we were unable to do more for them. It was all very much worth while, however, when one met a stretcher coming to the ward and heard some splendid American lad, perhaps minus an arm or a leg, say “Gee, but it’s good to see an talk to an American girl.

The unit sailed from France on April 13, 1919, arriving back home in San Francisco on May 15, 1919. Although formally demobilized on May 26, Base Hospital #30 would revive two decades later, ready to serve the wounded soldiers of World War II.

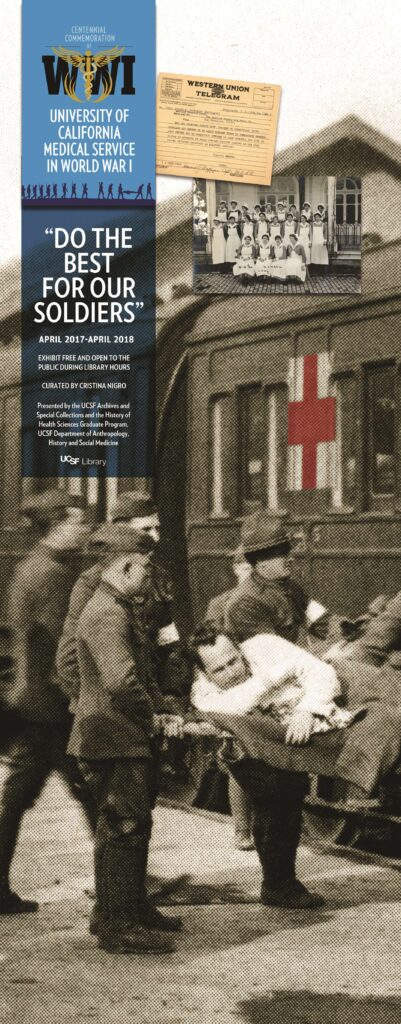

To learn more about UCSF’s role in World War I, save the date for our upcoming exhibit on Base Hospital 30 and the Great War, opening April 2017 at the UCSF Library.