This is a guest post by Cristina Nigro, UCSF History of Health Sciences graduate student and curator of the UCSF Archives WWI exhibit.

Each year on the last Monday of May, our nation commemorates U.S. service members from all wars who died while on active duty. On this Memorial Day we pay special homage to the servicemen and women of World War I, as 2017 marks the centennial anniversary of the U.S. entrance into WWI.

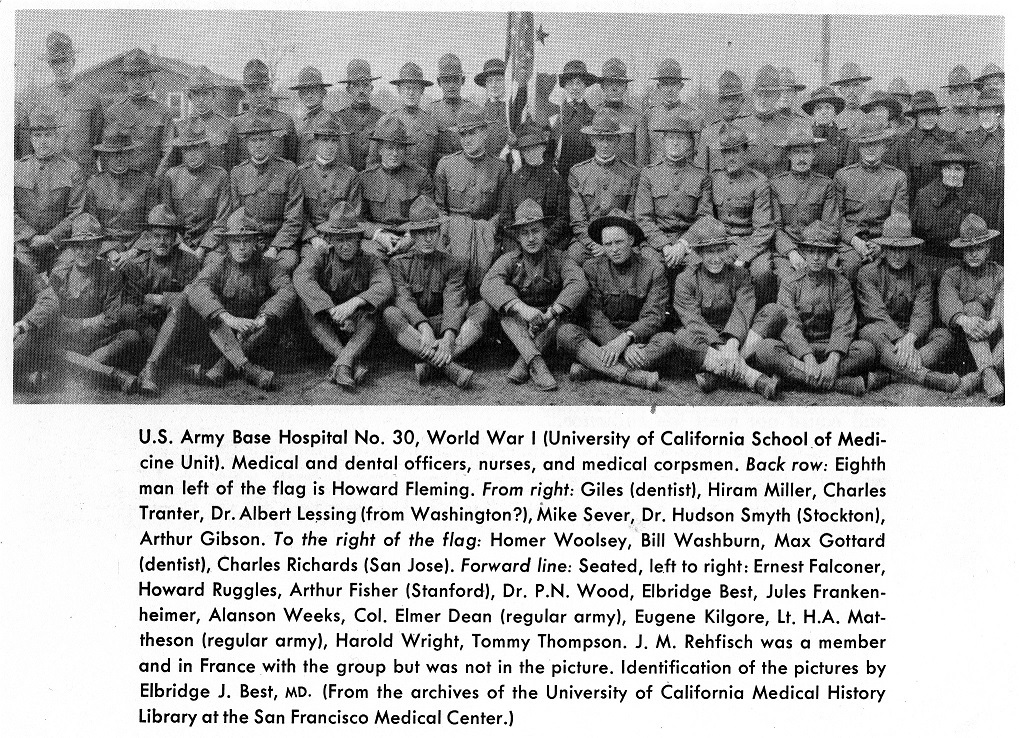

Dr. Elbridge Best, graduate of the UC Medical School class of 1911 who later joined the UCSF faculty, served in WWI at Base Hospital No. 30 in Royat, France. Base Hospital No. 30 was organized by the UC Medical School in March 1917—the month before President Woodrow Wilson asked a joint session of Congress to request a declaration of war with Germany. In a 1964 interview, Best recalled the early mobilization effort by him and his colleagues who “felt that the war was imminent” and who “were a little concerned with regard to the possible slowness of the White House deciding to declare war.”

Officers and enlisted personnel. From the John Homer Woolsey papers, MSS 70-5, box 1, photograph album.

Before leaving for the front, Best was put to work in the aviation unit established in San Francisco. He helped to medically examine applicants for the aviation corps in the summer and fall of 1917. Best was later transferred from the aviation unit to the Presidio in San Francisco. There, he “did regular duty until the mobilization of the Base Hospital 30 in November when we then stopped our other activities, lived as a unit until the transportation was arranged and we boarded the ship at Fort Mason to proceed down the west coast.”

The unit arrived in New York harbor in March 1918, staying at Camp Merritt for about a month before embarking on the journey abroad. Best recalled his experience with an influenza epidemic in New York at the time: “Many of the Army men were taken to the Rockefeller hospital for treatment. And each of the cases where fluid was found in the chest the procedure was to immediately insert a needle and draw the fluid. It became very evident that whenever we saw this done we would say to a friend that we will see this body in the morgue the next morning. So many of these boys died following the removal of the acute fluid that when we went to France we made it a rule never to draw any fluid off until after we were sure there was frank pus and it should be treated surgically. The result was that we lost none of those cases which were the cause of the high mortality at the Rockefeller hospital.”

Base Hospital #30 at Royat, France. From the John Homer Woolsey papers, MSS 70-5, box 1, photograph album

The staff of Base Hospital No. 30 arrived in Royat, France in May 1918. Best remembered that casualties were sent to the hospital soon after the unit arrived: “They came almost as soon as we had most of our material unpacked….The casualties from the front came down to us on trains, Red Cross trains, arranged with beds. And we removed the patients from the trains by way of the windows ordinarily. The one train was full of gas injuries, phosgene and mustard gas. Another trainload came all shot-up which the debridement had been done at the front. These trains ordinarily did not have mixed cases—they were usually all of one type—and they usually contained from four to five hundred wounded at a time.”

Best recalled suddenly learning of the armistice on November 11, 1918: “Everybody was elated and as soon as the evening meal was over on that day, all of those who were not on duty went the three kilometer distance to Clermont-Ferrand to celebrate this notable event…After the armistice, some of us had the privilege of visiting French families in various country areas…We would go and have tea with a certain family or we would have dinner with some people or they would have a reception in which French and American people in the vicinity would appear. I am particularly reminded of one French family we visited in a lovely, old-style two story wooden home on a farm…These people spoke no English and we had to converse in French. And the philosophy, the problems, the day-by- day incidents that these people would gossip with us about were exactly the same as those that we would encounter among families in similar positions in the United States. The only difference between these delightful people and the people in our homes were that they spoke French and we spoke English.”

Misses Dunn and Ireland [nurses] leaving Clermont-Ferrand. From the John Homer Woolsey papers, MSS 70-5, box 1, photograph album.

View more WWI images and documents from the UCSF Archives collections on Calisphere.