This is part 1 of a series of blog posts we will put together talking about some of our web-archiving activities at UCSF, and examining some of the changes in University web presences over the years we’ve been collecting them. How many parts will there be? We don’t know yet! The possibilities are endless, so we’ll just have to see where it takes us.

By way of some introduction, we here at Archives & Special Collections have been collecting website captures since about 2009. Initially we used a service maintained by California Digital Library called WAS (Web-Archiving Service), but we now use the Internet Archives Archive-It service to capture sites. We plan to use a later post to go into more detail about how Archive-It works, but for this blog post it suffices to know that Archive-It contains the technology that crawls the web-sites and saves them on the Internet Archives servers just down the road at their Clement St. headquarters.

So why do we do this? Currently, much of the history of the University and its various buildings, people, and internal organizations are all published on the web, so examining that history in the future will include looking at these web-sites to assess the way things have changed.

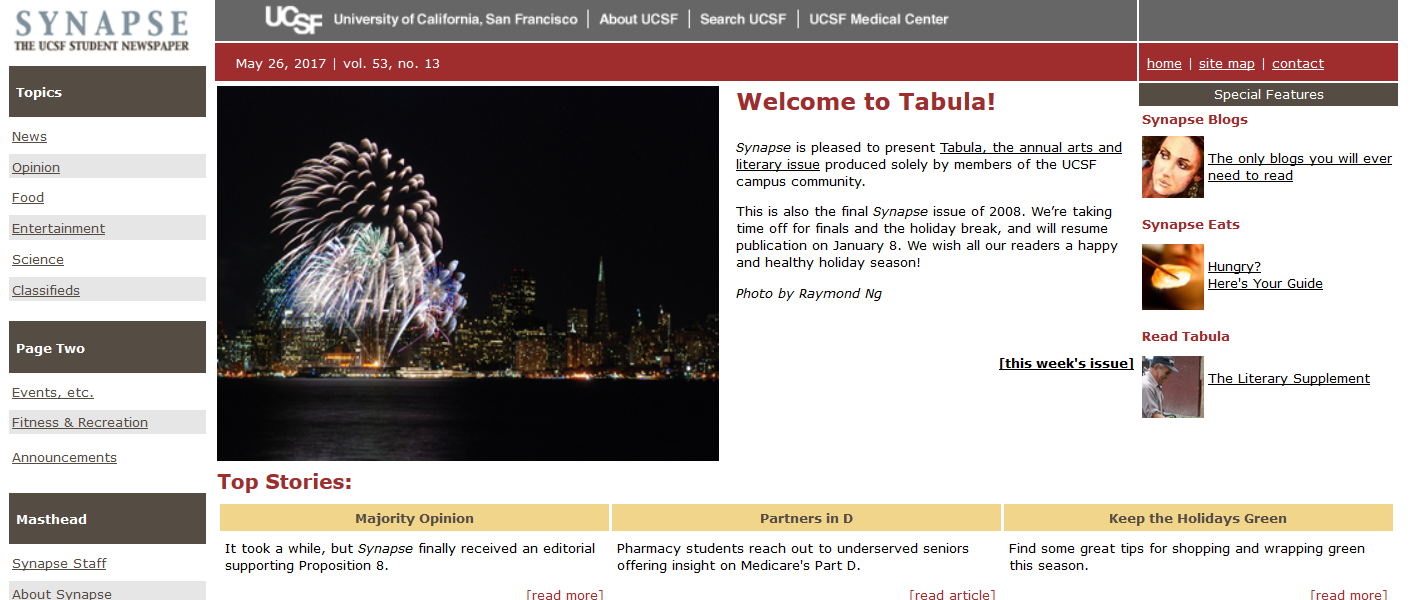

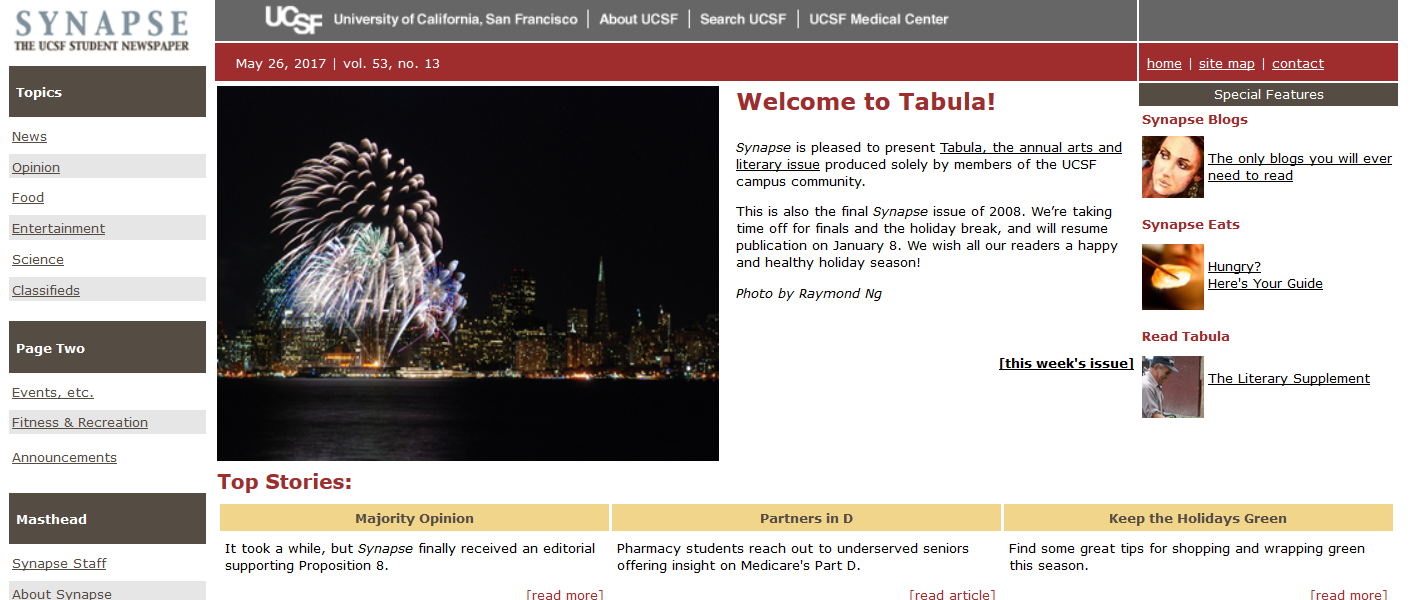

As an example, let’s look at the web page for Synapse, the UCSF Student Newspaper. Even since 2009, we can see significant changes in the look and feel of the web page, and can begin to tease out historical questions from the design and content of the pages.

Synapse home page in 2009. It looks pretty simple, and all the information is pretty static.

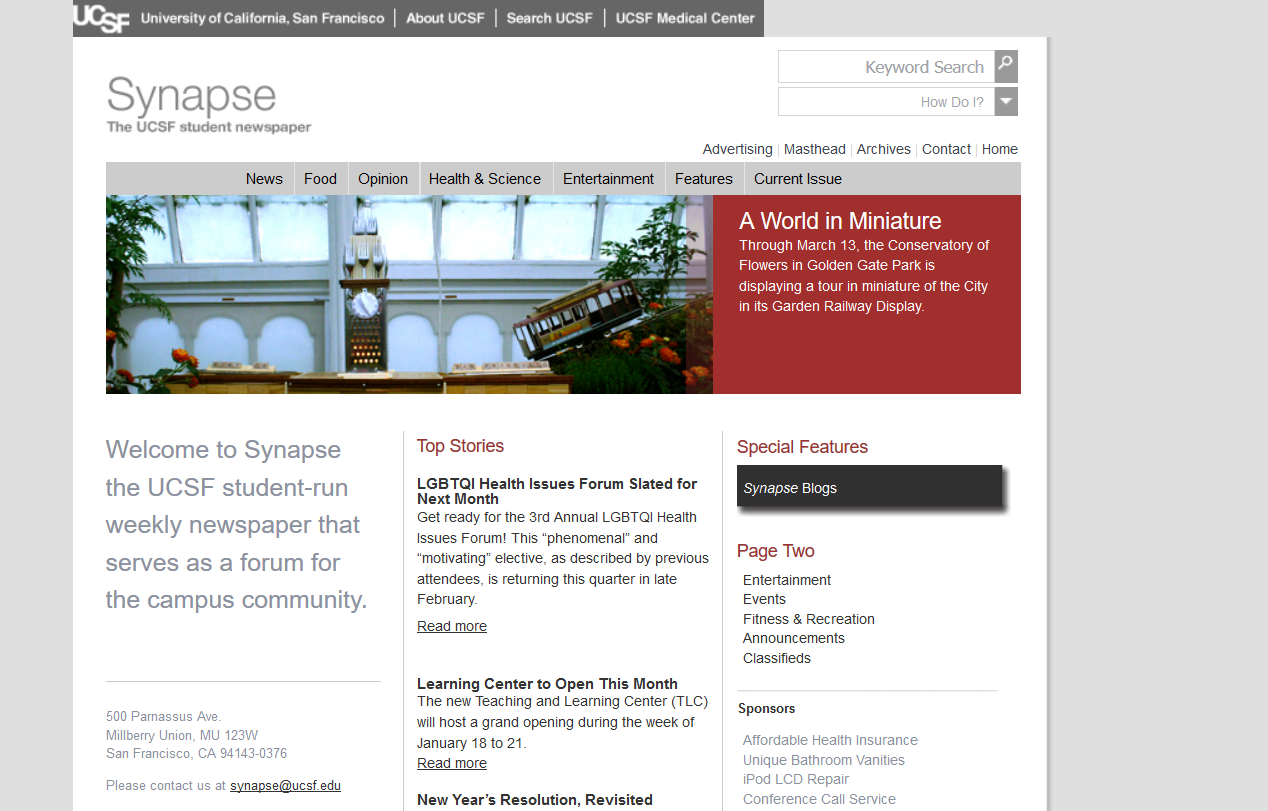

Synapse home page in 2011. It’s gone through a redesign, and perhaps looks a bit more like a newspaper now. It also contains some interesting pre-formatted search bars at the top right.

Already questions begin to emerge. Why did the staff institute search starting in 2011? And did the interesting “How Do I?” pre-formatted search bar get added to the page as a result of identified need for such searches? (I had never seen it before this)

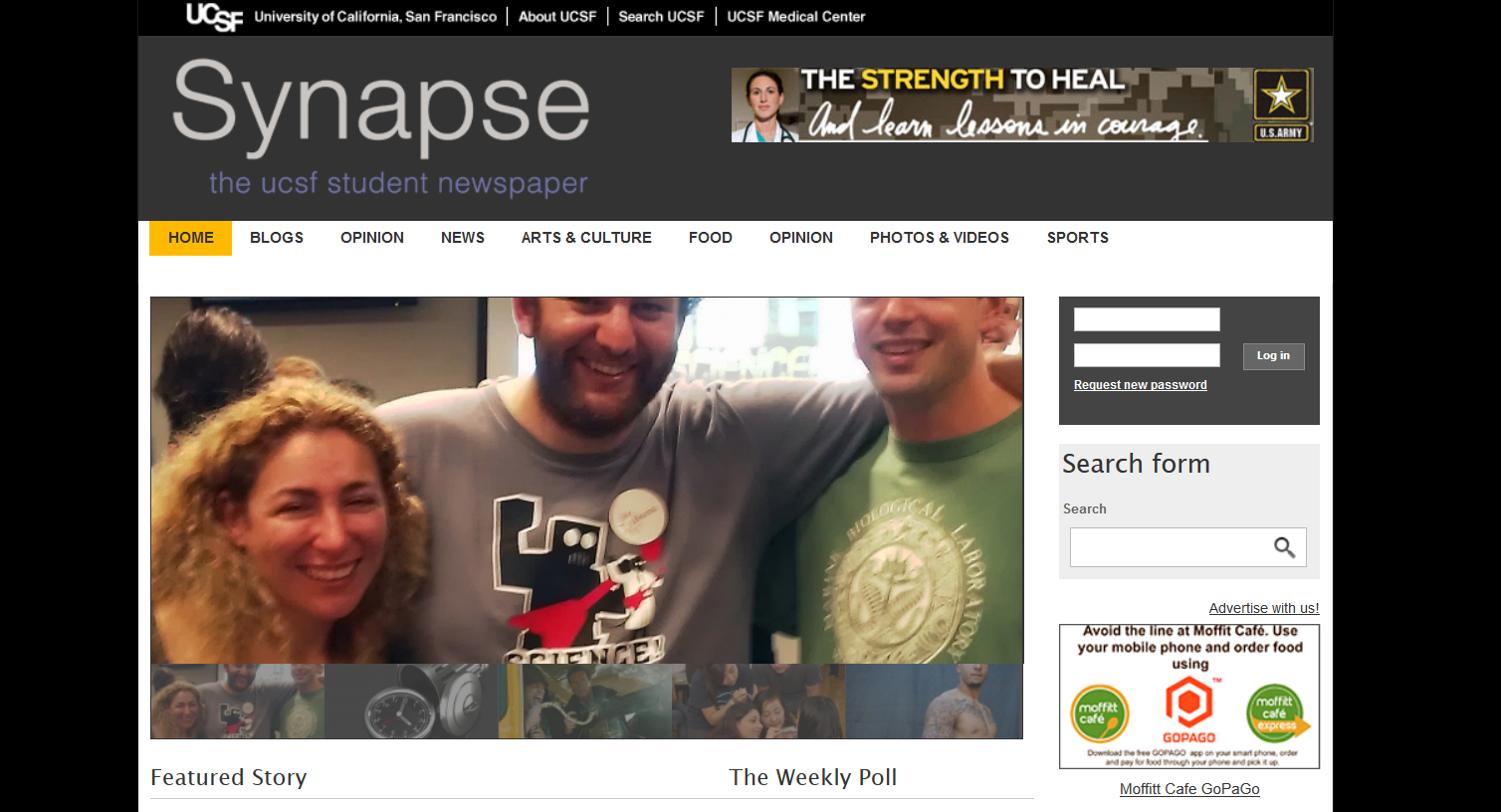

Synapse home page in 2013. It now contains a slideshow on the cover page, and has gone to a darker look.

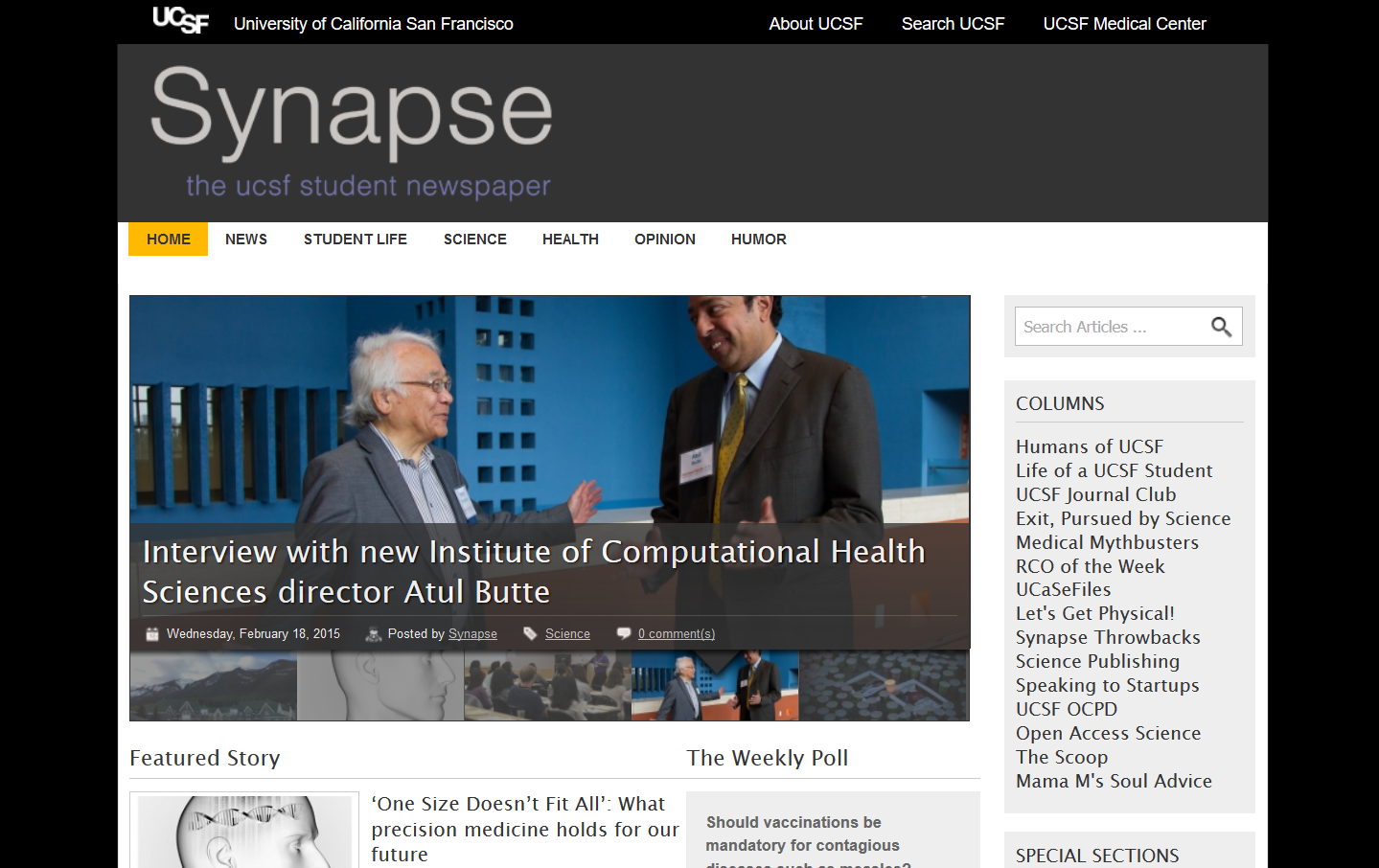

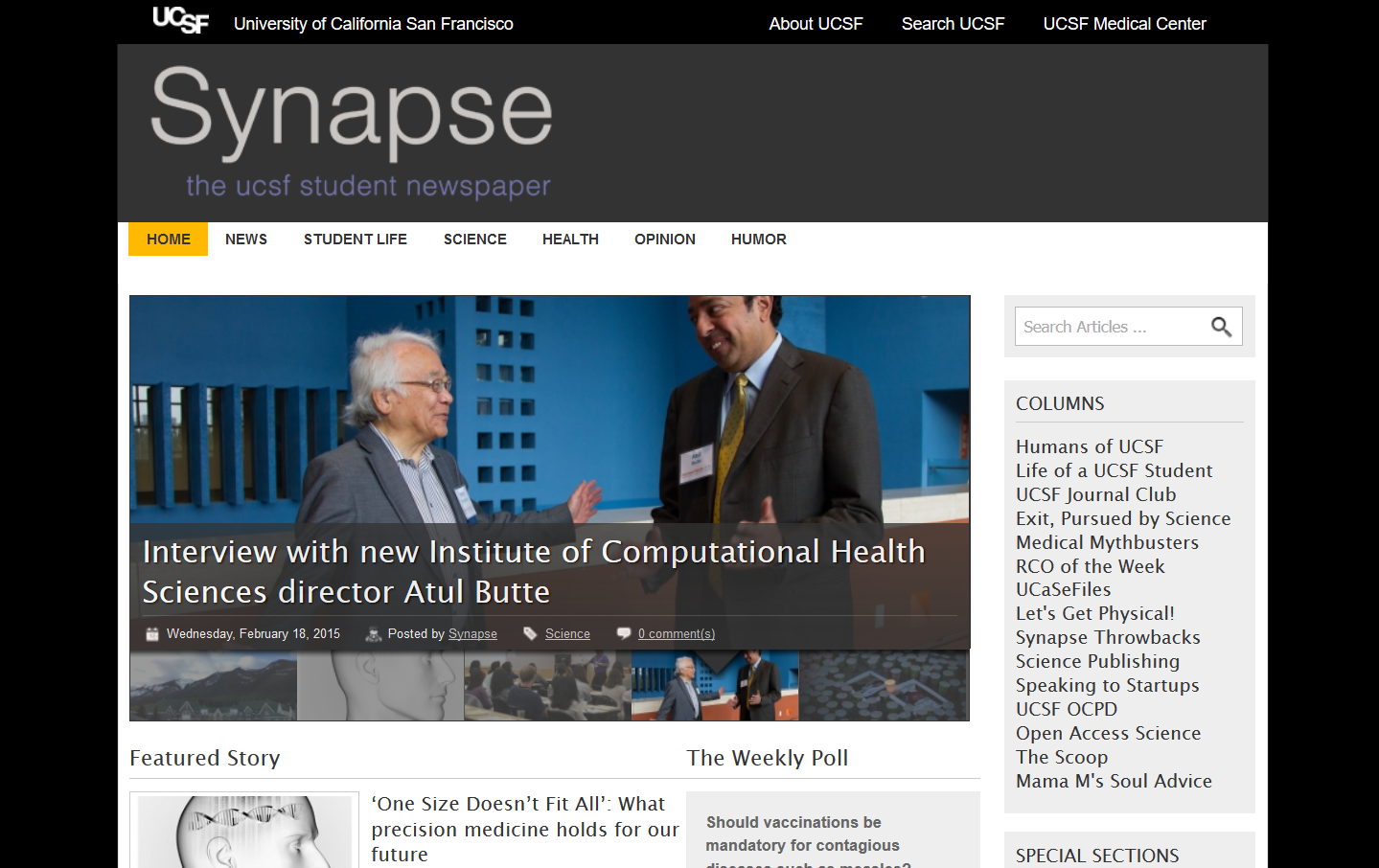

Synapse home page in 2015. It retains the same look, appears to have moved to a new slideshow technology, and just so happens to feature Dr. Atul Butte at the very beginning of his current position at the University.

Between 2013 and 2015 the paper got a new look for its home page, and introduced slide shows for the first time. Additionally the paper gained a “login” option in 2013 but that had been removed again by 2015 — perhaps a brief memory of the everything-must-be-social media phase of design. It’s also the first time that advertisements have appeared directly on the front page of the paper.

In these documents we can also begin to see the rise of precision medicine and computational health sciences at UCSF, and it’s clear that by 2015 the University was ramping up investment, and that this translated directly to the content of the newspaper as well.

Synapse home page in 2017. It now reflects the design we are used to with most sites we visit.

And finally the page today is in line with much of the design we are used to seeing at our most commonly-visited sites. Synapse also happens to be going back to the archives themselves in this latest update, and pulling content which is just distant enough to have a historical feel.

The aesthetic changes in the page also mirror the aesthetic trajectories of the way we think health and the health sciences should “look”. It makes sense that they’ve gone back to a mostly white color scheme — you’d have a hard time finding a contemporary web page for a hospital or health provider with a dark color scheme now.

Sometimes it can be hard to consider web pages as historical artifacts because we are so close to them, but we are now reaching a point where the first web pages we have collected look foreign enough to us that they are beginning to seem more worthy of study. And we’ve barely even mentioned the wealth of data about the way we communicate which is contained in our web-archives and which can be accessed and assessed with new computational historical methods.

You can find all the UCSF web-archives here: https://archive-it.org/organizations/986

What research will you do with them?