Today’s post is a brief update on the implementation of the Health Sciences Data Laboratory, a collaboration between the UCSF Archives & Special Collections and the Department of Anthropology, History, and Social Medicine (DAHSM). Last year DAHSM and the Archives were awarded a Resource Allocation Program (RAP) grant to purchase a high-throughput document scanner and begin the huge task of digitizing some of the more than 7 million historic patient files that track the development of care at Mt. Zion and UCSF Hospitals in the 20th century. These files contain a wealth of data – demographic, clinical, and public health – which has been mostly inaccessible on paper media for the life of the record. Electronic health records – data which was collected for clinical rather than research purposes – have already proven unexpectedly useful for epidemiological and public health research (Diez Roux, 2015). Similarly, this lab aims to make the valuable data contained in these records available for new computational access, and to bring a large body of historical records into the realm of big-data health science research.

But for right now, we’re figuring out how it all works! The scanner we were able to purchase is a powerful machine, and at max speed can scan almost 280 pages per minute. Because most of our documents are relatively-fragile paper from the 20s, 30s, and 40s, we scan at a slower speed than this. This helps us to minimize potential for damage of the records and optimize image quality and file size. Even at a slow speed however, this process is vastly improved by the new scanner, which can scan an entire stack of paper (700 pages when full) in one go. Formerly each page had to be scanned one by one, on a flatbed scanner which created only one image at a time.

The new sheet-fed scanner in the Health Sciences Data Laboratory.

Now that we’ve got the scanner working smoothly and a workflow in place, we’re hoping to begin ramping up production soon. Currently, our intern Maopeli is working on digitizing patient records in order to draw some small-scale research conclusions on the income-levels of patients at that time and how these related to specific health conditions that they experienced, research being done as part of an internship with the CHORI program.

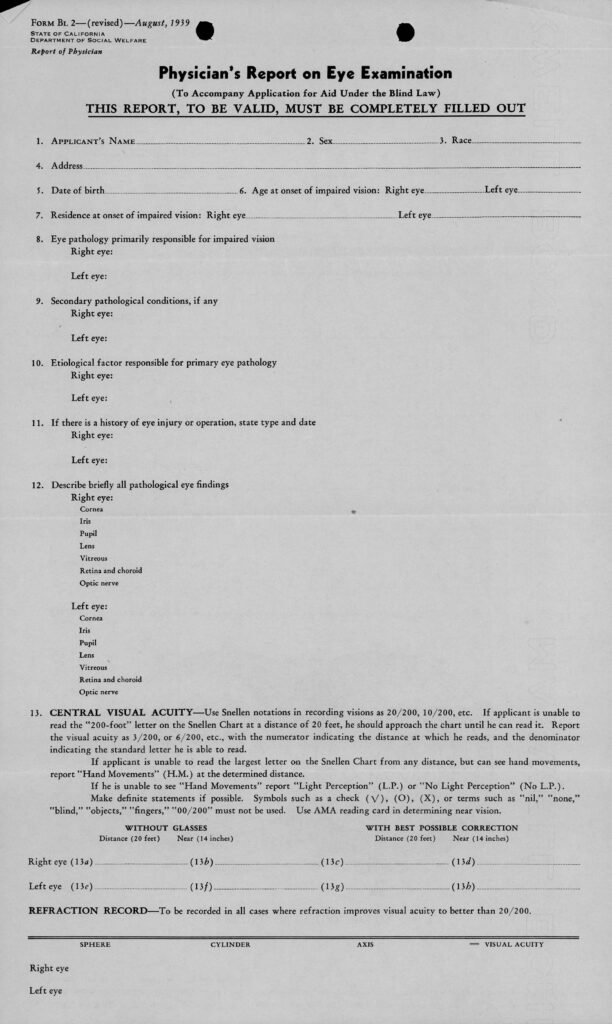

We hope not only to increase the rate of scanning (7 million records is a lot to get through!) but also to start exploring new ways to facilitate researcher access to this wealth of data. As evidenced by the image of a blank sample record, the data contained in these materials is both detailed and comprehensive, but it also requires a lot of labor, both human and computer, to make it computationally actionable. Much of it is handwritten and must either be transcribed or put through heavy-duty image processing algorithms which are more than most researchers have access to. For now though, we’re happy to be finally taking the first important steps as the first images and data from this vast trove make the transition from physical to digital.

An example of some of the types of data collected in patient records.