This is a guest post by Aaron J. Jackson, M.A, Ph.D. Candidate, UCSF History of Health Sciences.

From time to time, events in the present so closely resemble events from the past that the aphorism “history repeats itself” seems feasible. This can be demonstrated by comparing the current crisis of the novel coronavirus with the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919. The similarities are compelling. Like the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, the variety of H1N1 influenza that swept across the world in 1918 and 1919 produced a significant shock. It spread like wildfire, was frustratingly resistant to contemporary therapeutics, exhibited novel characteristics, and forced governments to resort to what some considered to be heavy-handed public health interventions. Bay Area residents in 1918 were required to wear masks and practice social distancing, just as they are required to do so today. Such historical similarities are not, however, proof that history repeats itself. But they do provide interesting opportunities for comparison between the past and the present—opportunities that hold the potential to make the past more relatable by building connections through common circumstances. And perhaps, through that understanding, an opportunity for hope to shine in dark times.

This post is not an exhaustive study comparing 1918 and 2020. Rather, it focuses on responses to crises and specifically the ways that communities innovatively addressed shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE). So, of course, it will be about war, pandemics, socks, and sheet protectors. Naturally.

When the United States declared war on the Imperial Government of Germany in April 1917, the nation was woefully unprepared for the conflict. The war represented an unprecedented crisis—one that required the federal government to assume new powers in order to coordinate the resources of the entire nation. President Woodrow Wilson’s administration worked with Congress to institute a draft to raise an army, enacted strict economic control measures to conserve and direct resources towards the production of war materiel, and passed laws that infringed on civil liberties, all in the name of the war effort. To ensure public support for these moves, the government mounted a massive propaganda campaign that appealed to a specific version of American patriotism, appealing to citizens’ sense of duty.

Mustering an army of sufficient size presented significant challenges. The men not only had to be inducted into military service—either by volunteering or being drafted—they required hundreds of training camps, transportation to those camps, equipment to train with, uniforms to wear. Once at the camps, they required food, shelter, and medical support. Military training was and remains a dangerous business, but the most significant medical problem at the cantonments was disease.

As tens of thousands of American recruits assembled at Army camps across the United States, they unwittingly brought diseases with them, which found ample opportunity to spread in cramped camp conditions. Most of these infections fell into the category of “common respiratory unknown disease”—an unofficial designation among military recruits who learned to add C.R.U.D. to the lexicon of military acronyms they learned. The crud largely consisted of the common cold and other respiratory infections, but cases of measles, mumps, and chicken pox were also common. Most cases of the crud cleared up without need for treatment, but the prevalence of these infections and the fact that new waves of infections would spring up with every new trainload of recruits had the effect of masking a more dangerous threat. Army physicians first identified more than 100 soldiers who had developed a rather severe flu-like illness in March 1918. Within a week, the number of flu cases at Fort Riley was over 500 and climbing. The H1N1 virus that caused the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 had arrived, but the nation was focused on the war. And as American troops began arriving in France and moving into the front lines—many of them no doubt bringing the virus with them—medical personnel tasked with supporting the war effort shifted their focus from induction screening and camp illnesses to other health concerns.

The First World War introduced a bevy of new ways to mangle and maim human bodies. From high-velocity rifle rounds and machine guns to high-explosive artillery shells, flamethrowers, hand grenades, aerial bombardment, and chemical weapons, the U.S. Army Medical Corps understood that the hospital system it established in France had to be prepared first and foremost for trauma care, which posed significant challenges. Not only did modern weapons cause extensive damage, the risks of sepsis and gangrene in an era before the discovery of antibiotics were high. Complicating this, European battlefields tended to stretch across agricultural land, teeming with bacteria after years of fertilization. Soldiers wounded on the front lines thus ran an extremely high risk of bacterial infection. To address this, the Medical Corps and its affiliates prioritized training Army health care workers in antiseptic wound care.

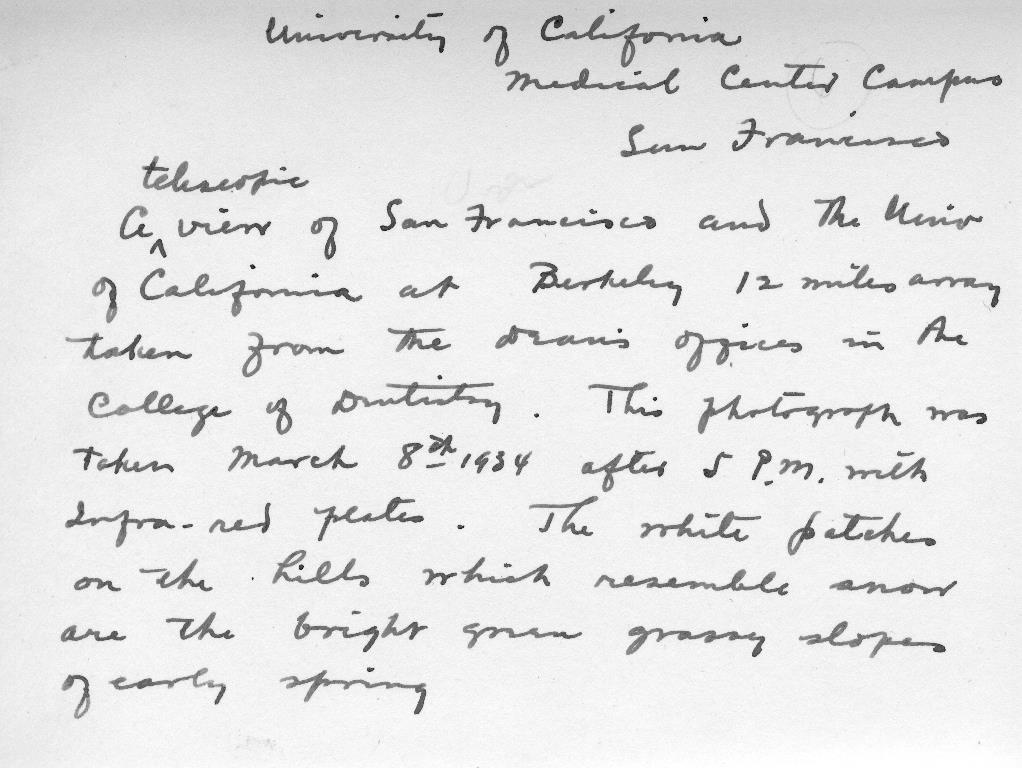

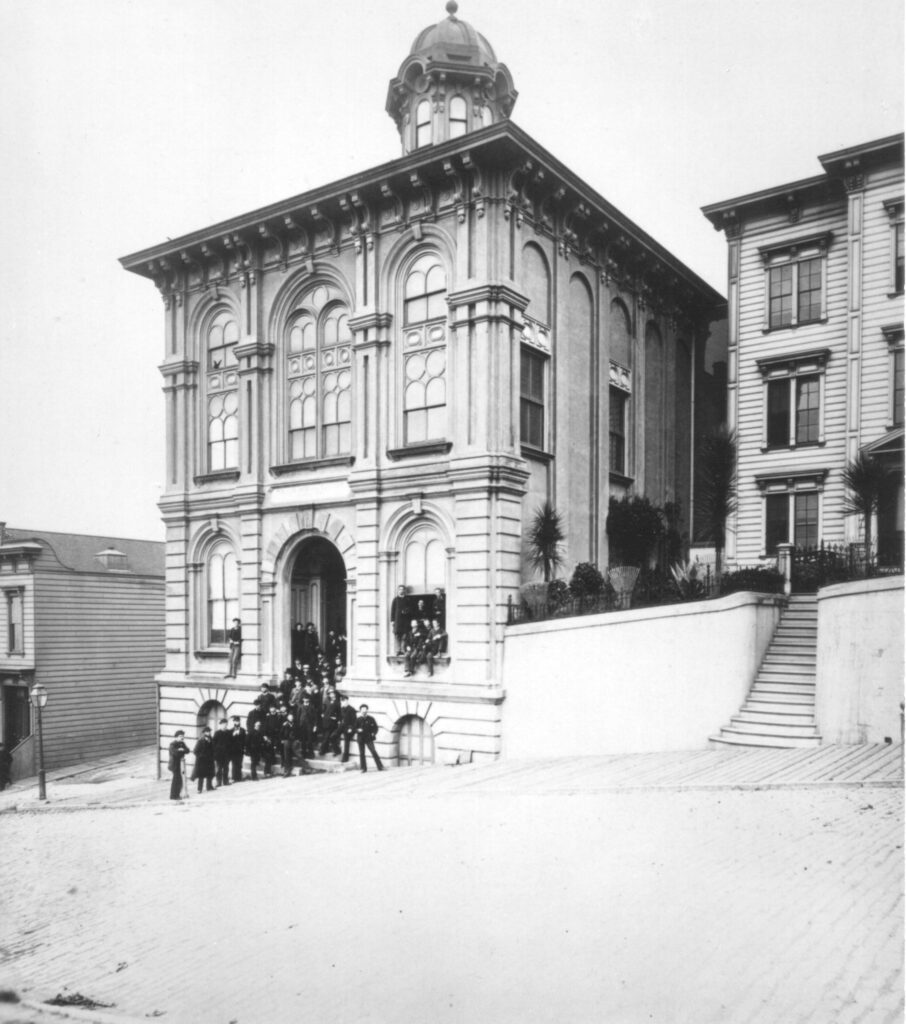

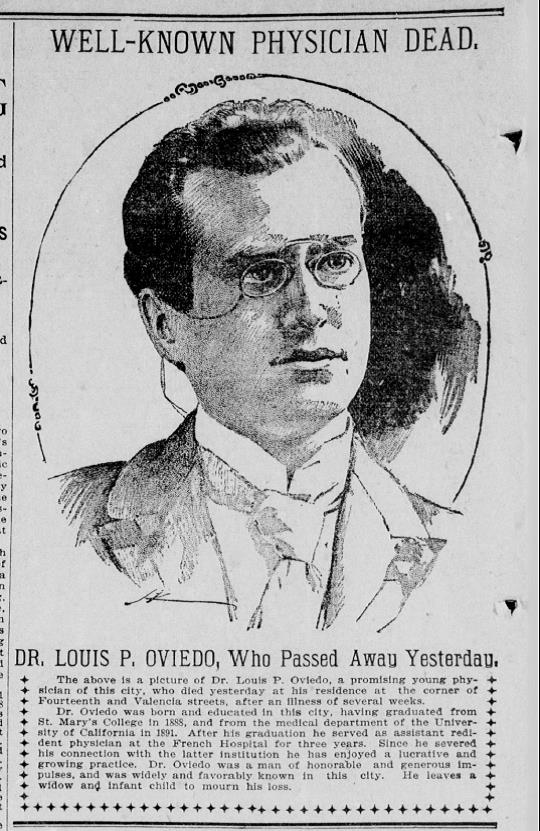

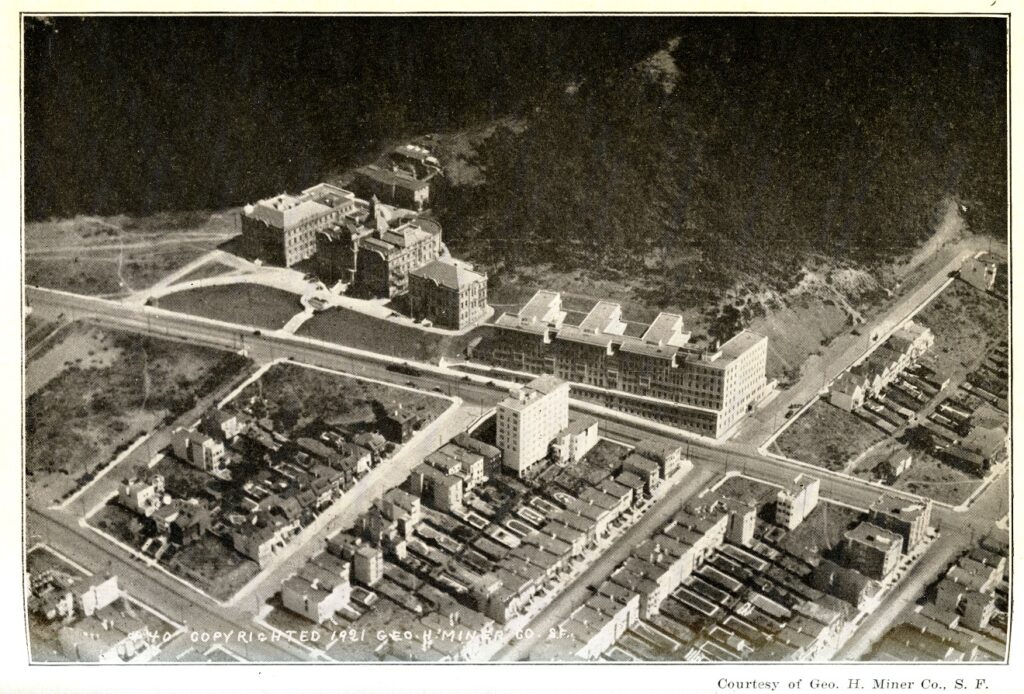

The experiences of the personnel of Base Hospital No. 30 are instructive in this regard. Base Hospital Thirty was the military hospital unit assembled from physicians, surgeons, and nurses associated with the University of California’s School of Medicine—the precursor to UCSF. Organized with the help of the American Red Cross Society shortly after Congress declared war, the unit spent more than a year training for the anticipated challenges of running a hospital for wounded soldiers in France. The unit’s nurses received orders to depart San Francisco on December 26, 1917 and reported to Army cantonment camps along the East Coast to help care for soldiers who had fallen ill with the crud, gaining invaluable experience in nursing soldiers and recognizing disease presentation. The unit’s surgeons practiced the ancient technique of wound debridement—removing foreign objects and cutting away dead and dying flesh to produce a clean wound—and attended clinical instruction that prepared them for the types of injuries they would face. And the unit’s corpsmen trained in the production and use of the Carrell-Dakin solution, a novel antiseptic more effective than carbolic acid and iodine but also a solution that required careful training and preparation. Thanks to training like this, the base hospital system was able to treat more than 300,000 sick and wounded soldiers with remarkably low mortality rates compared to previous wars.

Indeed, the medical apparatus and personnel organized to support the American Expeditionary Forces were well prepared for the anticipated hazards of the war. But in one of the remarkable parallels to the current coronavirus crisis, their job was perhaps made more difficult by the failure of American logistics in providing adequate personal protective equipment. But the shortage in 1918 was not one of N95 masks; rather, it was a matter of needing socks.

Today, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration defines PPE as “equipment worn to minimize exposure to hazards that cause serious workplace injuries and illnesses.”[i] Under this definition, and in the context of soldiering, a good pair of socks certainly applies. Trench warfare was a dirty business. It also tended to be cold and wet—the perfect climate for a condition known today as “trench foot.” Afflicted soldiers’ feet would go numb, swell, develop sore and infections, and in extreme cases become gangrenous, possibly requiring amputation. Obviously, this ran the risk of keeping soldiers from the front lines and thus undermining the war effort. But ensuring a plentiful supply of clean dry socks somehow slipped through the cracks of the Army’s logistical efforts to prepare for the war. Fortunately, the American Red Cross and thousands of civilian volunteers found ways to meet the challenge.

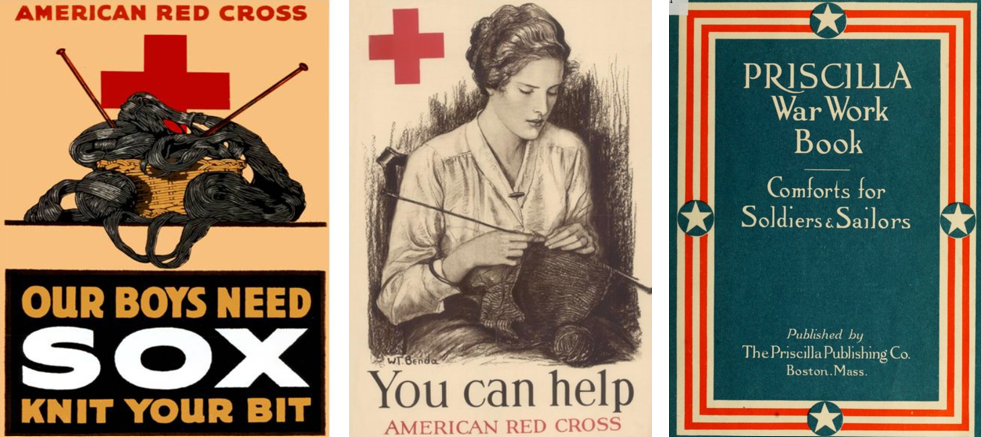

Beginning in 1917, the Red Cross put out calls for knitted garments, especially socks. The organization distributed officially-endorsed knitting patterns and free wool to anyone willing to “knit your bit.” The Priscilla War Work Book contains roughly a dozen such patterns ranging from socks to coats and winter hats.[ii] But the demand was greatest for socks. Across the country, knitters worked individually at home and collectively in social groups to try to keep up with the demand. Those who could not knit were urged to purchase or donate wool for the cause. Some organizations turned to mechanical solutions. The Seattle Red Cross utilized a knitting machine to produce long wool tubes that could be cut into 27-inch lengths, requiring only the toes to be stitched by hand.[iii] In this way, those behind the front lines were able to support the war effort by providing the PPE the soldiers needed to keep themselves in fighting shape.

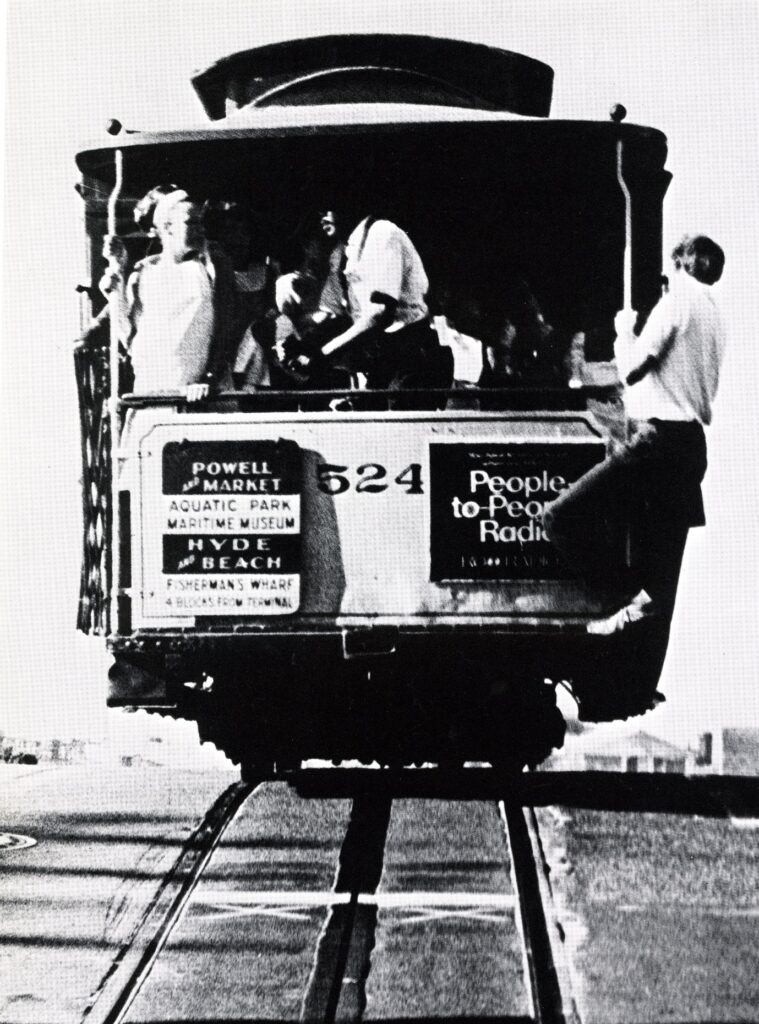

Celebrating the end of the First World War in San Francisco, November 11, 1918. Image from The San Francisco Chronicle files.

The knitting campaign continued until the war ended with the declaration of the armistice on November 11, 1918. By then, the nation was in the midst of the first wave of the influenza pandemic. On October 9, 1918, San Francisco’s hospitals reported 169 influenza cases. A week later, there were more than 2,000 and the city’s Board of Health issued recommendations for social distancing.[iv] With so many health care professionals supporting the war effort, the Bay Area’s medical infrastructure was stretched to the limit and cities put out calls for volunteers. Hospital space soon became a valuable commodity and many facilities, including the Oakland Municipal Auditorium, were converted into temporary hospitals, and public health officials began recommending the use of face masks, which they later made mandatory.[v] But it is important to remember that these were local efforts to respond to the pandemic. The federal government, which had mustered the resources of the entire nation to fight the war in Europe, was unwilling to do the same to combat the pandemic at home, leaving it up to local authorities, medical institutions, and volunteer organizations to make do as best they could.

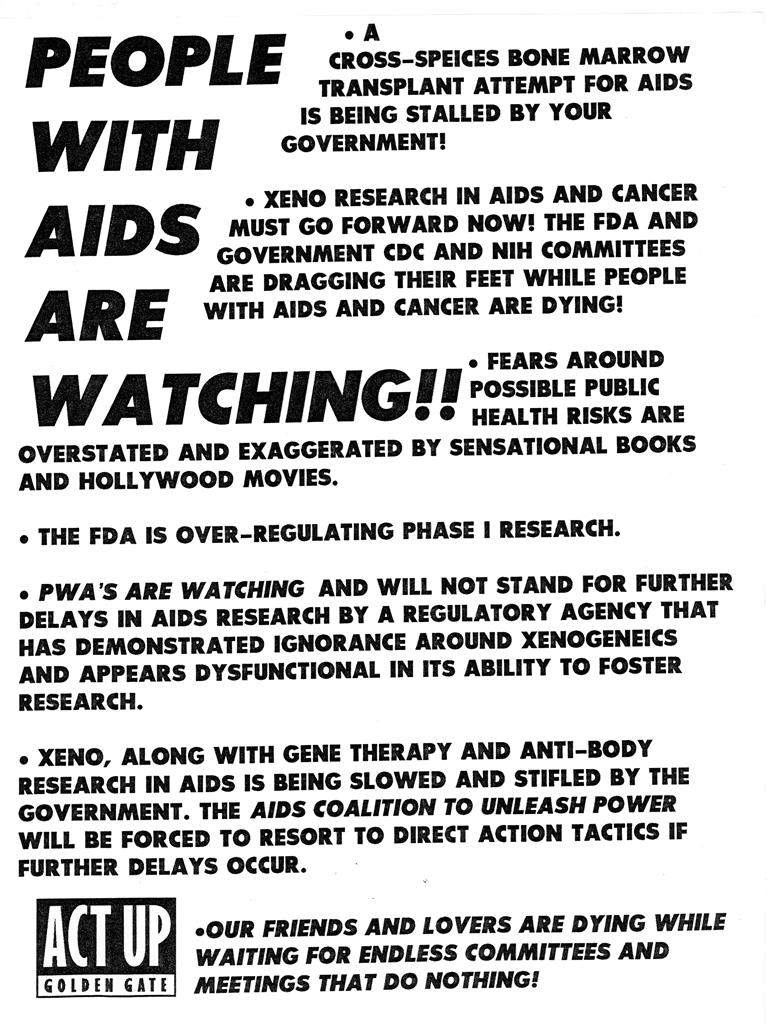

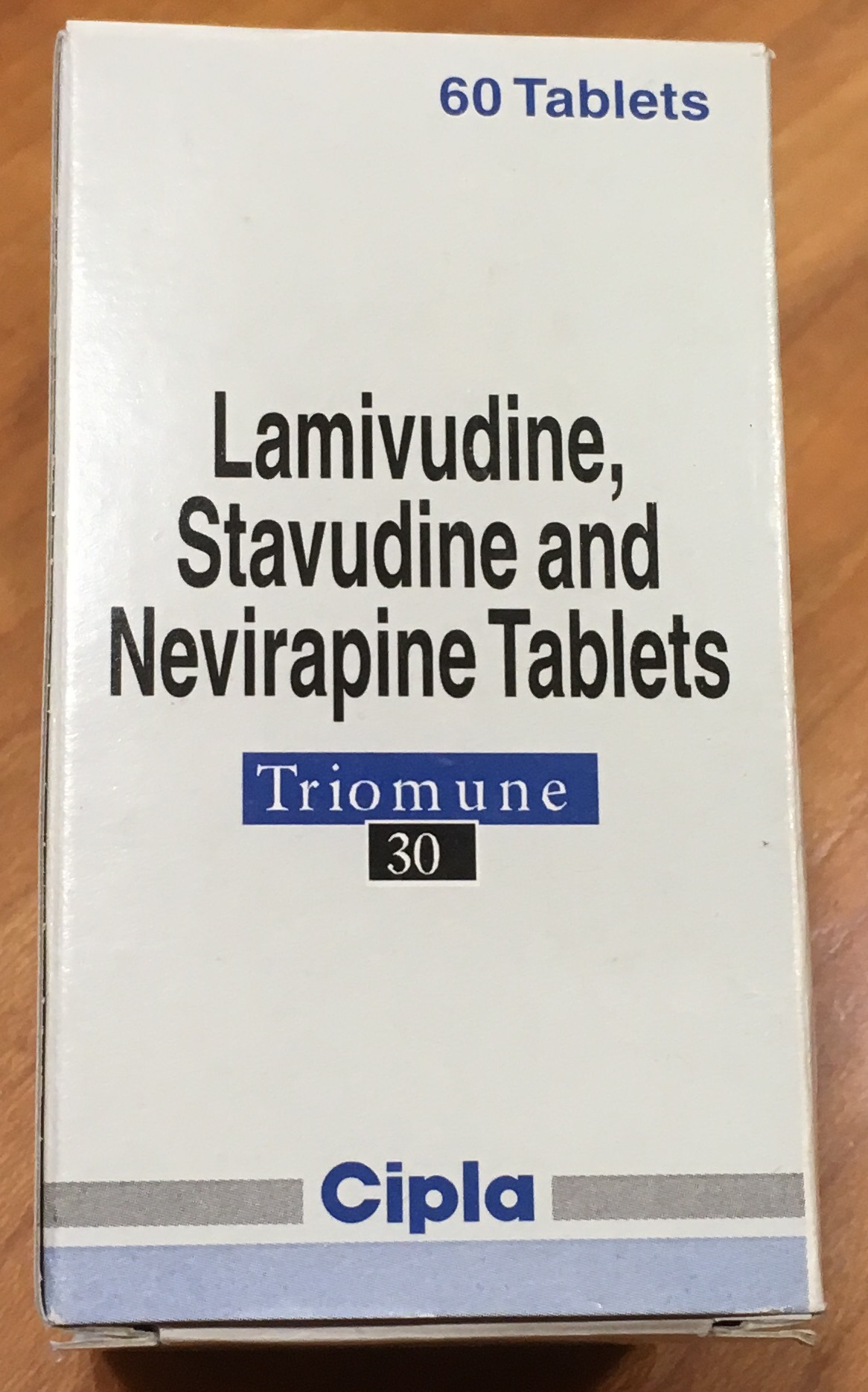

Unfortunately, we find ourselves in a similar situation today. As the novel coronavirus took on pandemic proportions, stores of PPE for frontline healthcare workers reached critical levels. Before the pandemic, China produced approximately half the world’s supply of medical masks. As the infection spread in China, their exports stopped, and the resulting shortage spurred competition between institutions and governments to secure PPE, which only exacerbated the situation. Thankfully, a multidisciplinary team at UCSF found a way to be a part of the solution, echoing the efforts of American knitters from over a century ago.

Noting the need for face shields, experts at UCSF specializing in biochemistry, engineering, logistics, medical workplace safety, and 3D model design came together in March 2020 to develop something that could help address the PPE shortage. By April, the team completed designs for three different models of 3D-printable face shield frames that, when combined with rubber bands and transparent document protectors, serve as functional and reusable face shields. They then collected seventeen 3D printers from across the university and turned the UCSF Makers Lab in the Kalmanovitz Library into an ad hoc face shield factory that can produce more than 300 shields each day—enough to supply UCSF’s front-line health care workers and then some.[vi] Extra shields are distributed to Bay Area hospitals. Moreover, like the Red Cross with the distribution of the Priscilla War Work Book, the UCSF team is sharing their plans in an open source repository so that others can emulate their efforts.[vii] This allows those with access to 3D printers and a few dollars’ worth of office supplies to contribute to the ongoing PPE shortage by producing face shields that have been designed, tested, and vetted by experts at one of the nation’s leading medical institutions.

Certainly, there are remarkable similarities to be drawn between the modern crisis and those in the past. Once again, the government was unprepared for a crisis despite advanced warning. Once again, people are working in the front lines to save others despite inadequate supplies. And once again, like the First World War and the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919, the coronavirus pandemic is a devastating event likely to be measured in the tally of lives lost. In the face of such grim statistics, it is easy to fall into cynicism and say that history is repeating.

In 1905, philosopher George

Santayana explored the notion of progress—the idea that things move toward

improvement—and stated that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned

to repeat it.”[viii]

This is likely the origin of the aphorism “history repeats itself.” But Santaya

was not making a hopeless argument; rather, he noted that if progress is to be achieved,

it will be because humans not only record the past, they engage with it, learn

from it, and seek to understand it. And how that is achieved depends on the

ability to draw relatable connections with the past that emphasize human

agency. In 1918, knitters took up their needles. Today, a team of scientists,

engineers, and others figured out how to make face shields using 3D printers

and office supplies. These may seem like small contributions in the grand

scheme of things, but they are important examples of positive human agency in

the face of crisis.

[i] Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “Personal Protective Equipment.” http://osha.gov/SLTC/personalprotectiveequipment/

[ii] Elsa Schappel Barsaloux and the American National Red Cross, The Priscilla War Work Book: Including Directions for Knitted Garments and Comfort Kits from the American Red Cross, and Knitted Garments for the Boy Scout. Boston, Mass.: The Priscilla Publishing Company, 1917. Available at the HathiTrust Digital Library. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/loc.ark:/13960/t2988wd21

[iii] Paula Becker, “Knitting for Victory – World War I,” Historylink.org, 2004. https://www.historylink.org/File/4721

[iv] “Thirty-Seven New Cases Found in S.F.,” San Francisco Chronicle 10 Oct. 1918, 3; “Hassler Urges Churches and Theaters to Close,” San Francisco Chronicle 17 Oct. 1918, 5.

[v] “Wear a Mask and Save Your Life!” San Francisco Chronicle, 22 Oct. 1918.

[vi] Robin Marks, “Lifesaving Face Shields for Health Care Workers are Newest 3D-Printing Project at UCSF,” University of California, San Francisco. April 7, 2020. https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2020/04/417101/lifesaving-face-shields-health-care-workers-are-newest-3d-printing-project-ucsf

[vii] Jenny Tai, “UCSF 3D Printed Face Shield Project,” UCSF Library, April 1, 2020. https://library.ucsf.edu/news/ucsf-3d-printed-face-shield-project

[viii] George Santayana, The Life of Reason. 1: Reason in Common Sense, Reprint (New York: Dover Publications, 1982), p. 284. Available at the Gutenberg Project. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/15000/15000-h/15000-h.htm