Introduction by Polina Ilieva

During the spring semester 2018 the archives team co-taught and facilitated a new History of Health Sciences course, the Anatomy of an Archive. The idea of this course was conceived by the Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine (DAHSM) Assistant Professor, Aimee Medeiros and UCSF Head of Archives & Special Collections, Polina Ilieva. Kelsi Evans, Project Archivist, co-facilitated the discussion sessions and Kelsi, Polina and David Uhlich, Access and Collections Archivist, served as mentors for students’ processing projects throughout the duration of the course.

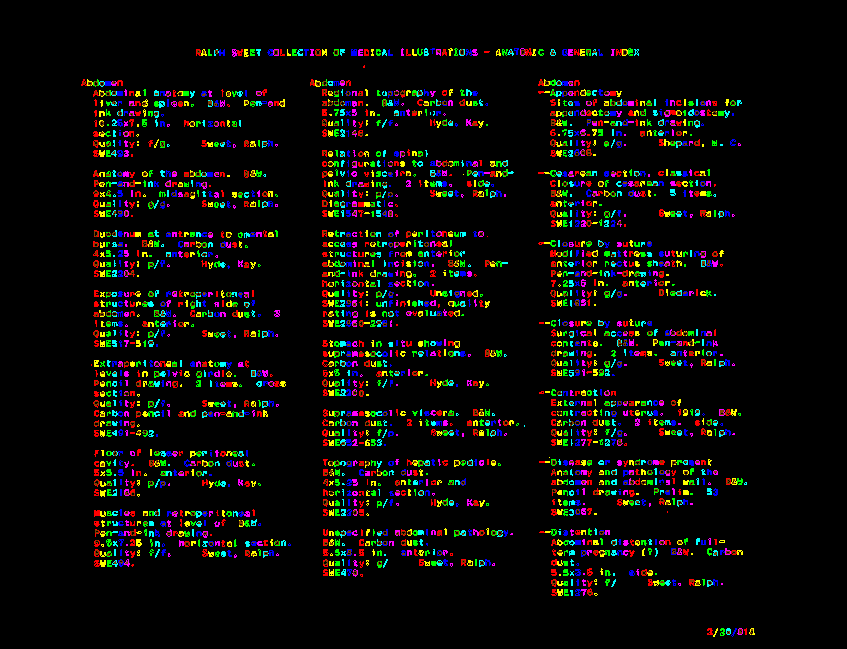

The goal of this course was to provide an overview of archival science with an emphasis on the theory, methodology, technologies and best practices of archival research, arrangement and description. The archivists put together a list of collections requiring processing and also corresponding to students’ research interests and each student selected one that she/he worked on with her/his mentor to arrange and create a finding aid. During this 10 week long assignment students developed competence researching and describing an archival collection, as well as interpreting the historical record. At the conclusion of this course students wrote a story about their experience and collections they researched for the archives blog. In the next three weeks we will be sharing these posts with you.

This week’s story comes from Aaron J. Jackson, PhD student, UCSF Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine.

Post by Aaron J. Jackson

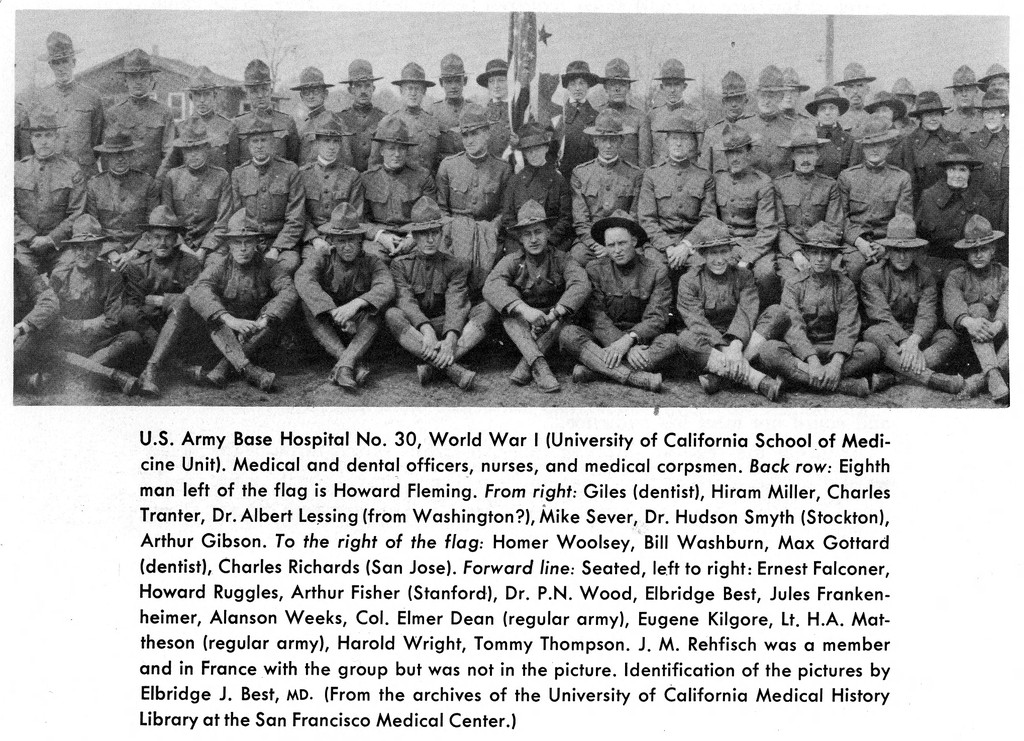

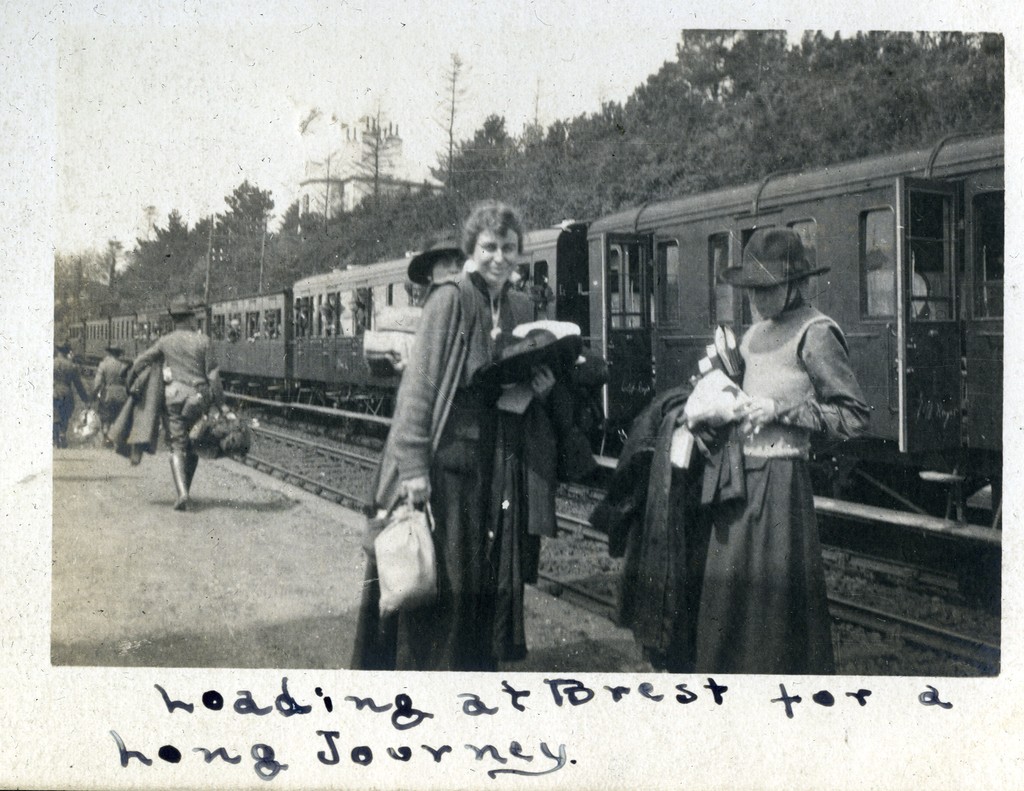

In the Spring term of 2018, my fellow History of Health Sciences (HHS) students and I in the UCSF Department of Anthropology, History & Social Medicine (DAHSM) had the opportunity to take a class on archival science with the staff of the UCSF Archives and Special Collections. Led by Archivist Polina Ilieva, Ph.D., and DAHSM Assistant Professor Aimee Medeiros, Ph.D., this class provided us with an overview of archival science with an emphasis on theory, methodology, and best practices of archival research, arrangement, and description. Most of us had used archives in the past—I even had experience with the UCSF Archives and Special Collections through a blog on the experiences of Base Hospital No. 30 in the First World War—but few of us really understood how archives work, how collections are cultivated and maintained, or the considerations that go into archival collection, assessment, processing, preservation, and presentation. This class provided us with a rare insight into a sector of knowledge production that is all-too-often taken for granted by historians.

UCSF Archives and Special Collections Reading Room and Parnassus Storage Facility.

Many historians and other scholars—myself included, before this class—believe that archives are mere repositories of historically-important data, objective interlocutors who merely preserve the past. Material is collected, inventoried, and stored for future researchers to come along and “discover” the contents and subsequently draw out the stories therein; yet, this is a myth, and one that Drs. Ilieva and Medeiros intended to dispel in their students. To achieve this task, students were allowed to choose from a list of as-yet unprocessed collections. We would be assigned an archivist mentor and process the collections while also meeting each week for a seminar discussion on the historical development and modern concerns of archival science. With my own interests rooted in the history of veterans’ care, I choose the Renée Hoffinger papers because the accession record indicated (with my emphasis) “Renee Hoffinger, MHSE, RD worked in the field of substance abuse for over 20 years at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System in Gainesville, FL.” While I did not find much of use for my own research, what I discovered while processing the Renée Hoffinger papers will undoubtedly prove to be far more beneficial in the long run.

The Provenance of the Renée Hoffinger Papers

Renée Hoffinger, MHSE, RD, image from “Dietetic Career Spotlight: Renée Hoffinger, MHSE, RD,” by Sarah Koszyk, MA, RDN, https://www.nutritionjobs.com/blog/blog/dietetic-career-spotlight-renee-hoffinger-mhse-rd/, accessed June 3, 2018.

Renée Hoffinger has been a dietitian since 1982 and interested in nutrition and HIV/AIDS since pursuing a health sciences education in the 1990s. While processing her collection, I had the pleasure of being able to correspond with Renée about her collection and why she donated her papers to UCSF’s AIDS History Project. She noted that her experience of researching HIV/AIDS and providing care for patients in Gainesville was vastly different—in terms of support and information availability—than that of health professionals in larger cities like New York, San Francisco, and Miami. During her volunteer work at the North Central Florida AIDS Network, Renée said she was “given a desk and access to patients at the HIV clinic at the local health [department], and spent a lot of time at the medical library tracking down any information I could get my hands on…. Not feeling like I knew very much, I soon unwittingly became the local ‘expert’ on nutrition and HIV.” Renée spent the rest of her career working with other dieticians interested in HIV/AIDS, and even after her retirement in 2013, she has continued writing about and leading hands-on nutrition education workshops. She had heard about the UCSF AIDS History Project and reached out to Archivist Polina Ilieva to find out how she could contribute, and so she decided to donate her papers to the archive.

This story reveals more than just the background of how Renée Hoffinger’s papers ended up at UCSF to be processed by a first-year Ph.D. student in the HHS program. It provides an anecdotal example of how collections end up in archives. Polina Ilieva’s background as an archivist does not make her an expert in HIV/AIDS nutrition, but it does give her training and insight into what future researchers may look for when investigating the history of AIDS and how contemporary medicine attempted to address it. Renée Hoffinger’s papers are stored at UCSF because they provide a small window into how parts of the country outside the urban epicenters of the disease and aspects of medicine not usually associated with the disease dealt with the epidemic’s effects. Thus, Ilieva decided to choose to take on the archival responsibility for the Hoffinger papers—to assess their potential value, to inventory and process their contents, to build finding aids that would serve future researchers, and to be responsible for maintaining the artifacts in the collection for the use of future generations. But she could have just as easily chosen to leave the responsibility to others for any number of reasons including limited archival space and funding, or because the archivist felt the collection would be a better fit elsewhere. In other cases, archivists actively solicit new collections, seeking permission to preserve the data. The decision to donate/accept the papers was therefore only the first step in the archival preservation of data, and it calls to question: what is missing from archival collections, and why?

Archival Concerns and Overhead

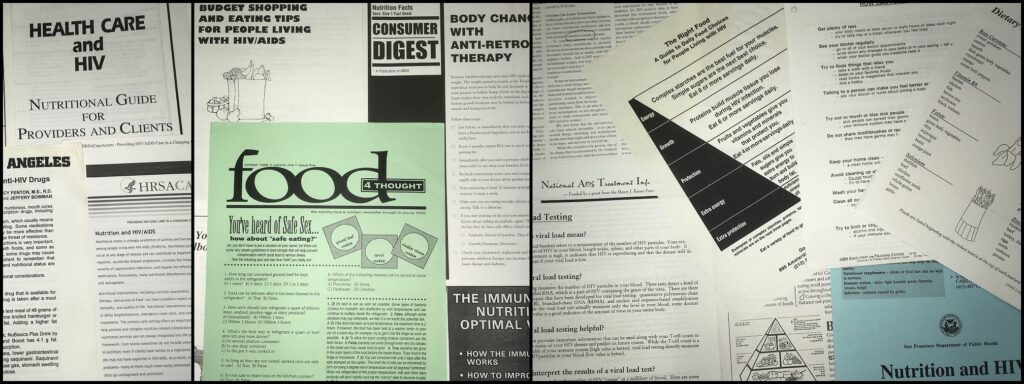

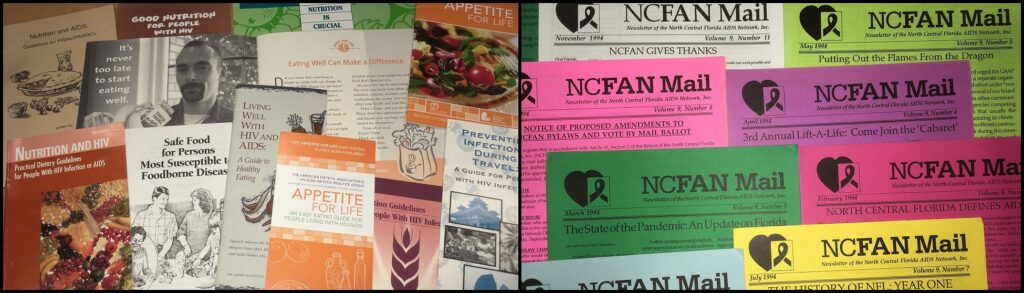

A Selection of HIV-AIDS Nutrition Documents from the Hoffinger (Renée) Papers at UCSF.

The story of how the Hoffinger papers came to reside in UCSF’s archives was only the beginning of a journey in what, at times, could seem like a foreign country. The archives have a unique vocabulary and vernacular. Archivists may speak of the accession or deaccession of artifacts or collections. Their language includes terms like “provenance” and “fonds” as well as concepts like “original order” and “finding aids.” Many of these terms may seem somewhat familiar, but their meaning within the archival space can often be different than the assumptions of those outside it, and those meanings can change over time, which is only one of the difficulties that archivists have to navigate in their mission to collect, preserve, and process archival collections. They put a great deal of work into cultivating collections, processing their contents in accordance with laws, regulations, and industry standards, and making the product of that work available to their target audience, which is often the public but may be restricted in some cases. For example, archivists at healthcare institutions like UCSF must pay special attention to the privacy restrictions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). They also need to concern themselves with copyright protections and dozens of other concerns, including securing funding and finding the manpower to process and reprocess miles of archival material. For reference, a 12 x 10 x 15 inch banker’s box contains only 1.25 linear feet of material by archival measurement standards—all of which requires storage space that not only protects the archived data but makes it available to public access. Digitization of archival material puts more stress on archivists’ time and resources, not less, as someone has to digitize the materials and provide for electronic storage and access points, often in addition to caring for the original documents. And all of this can be further complicated by unwilling donors. Some communities, particularly those who have been traditionally marginalized, are difficult to archive, requiring archivists to build long-neglected relationships and partnerships to preserve those aspects of history. In other cases, such as the UCSF Industry Documents Library, many of the contents are collected through court order from institutions who are less than thrilled to be forced to hand over internal documents. Such collections often require extraordinary processing efforts precisely because the donors are uncooperative, leaving the archivists to do their best to understand and arrange the documents in a useful manner.

The Contents of the Renée Hoffinger Papers

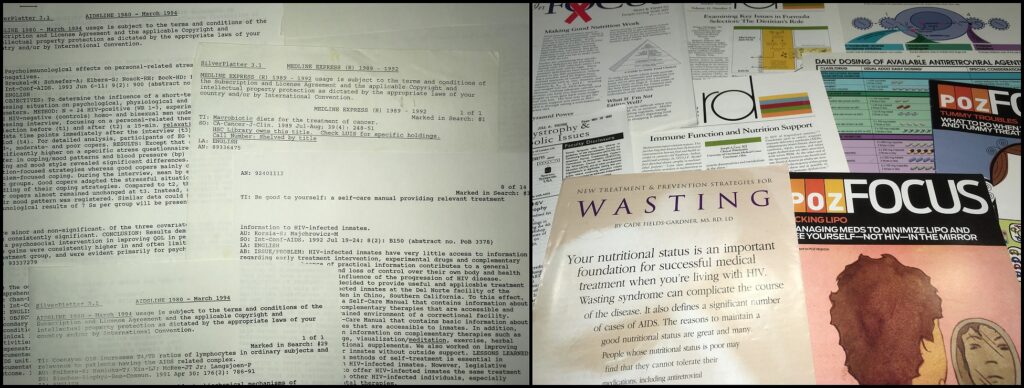

The Hoffinger Collection Contains AIDS Line Documents and Industry Publications.

In the case of the Hoffinger papers, the process was relatively straightforward. Renée Hoffinger, being alive and well at the time she deeded her papers to UCSF. The collection includes no patient records, so HIPAA was not a concern. Some of the documents are protected under copyright and therefore not likely to be digitized and posted online, but researchers are always welcome to view the documents in person. Regardless of the relative simplicity of this collection, I realized that what goes into the archives is very much the result of a creative and complicated process of selection, compliance, and access on the part of both the author of the papers and the archivists who collect and process them. In other words, archivists play an important role in precisely what is preserved, and this is something that researchers should keep in mind.

Patient Handouts & North Central Florida AIDS Network Newsletters.

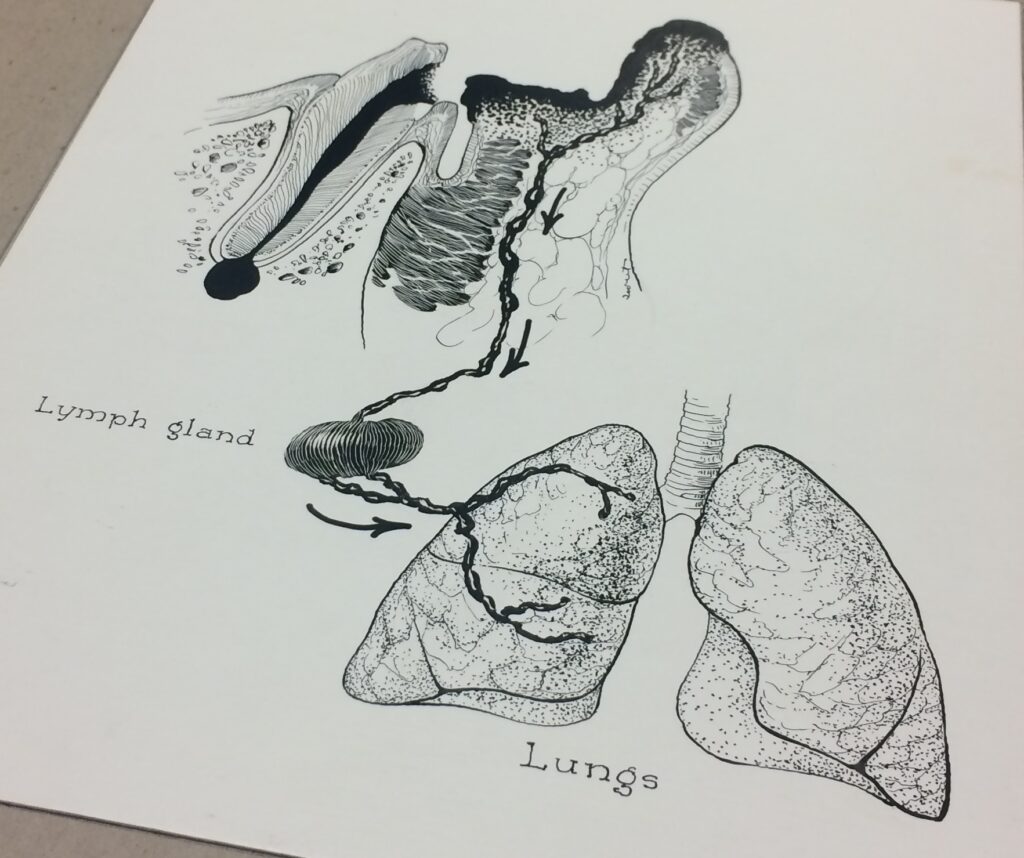

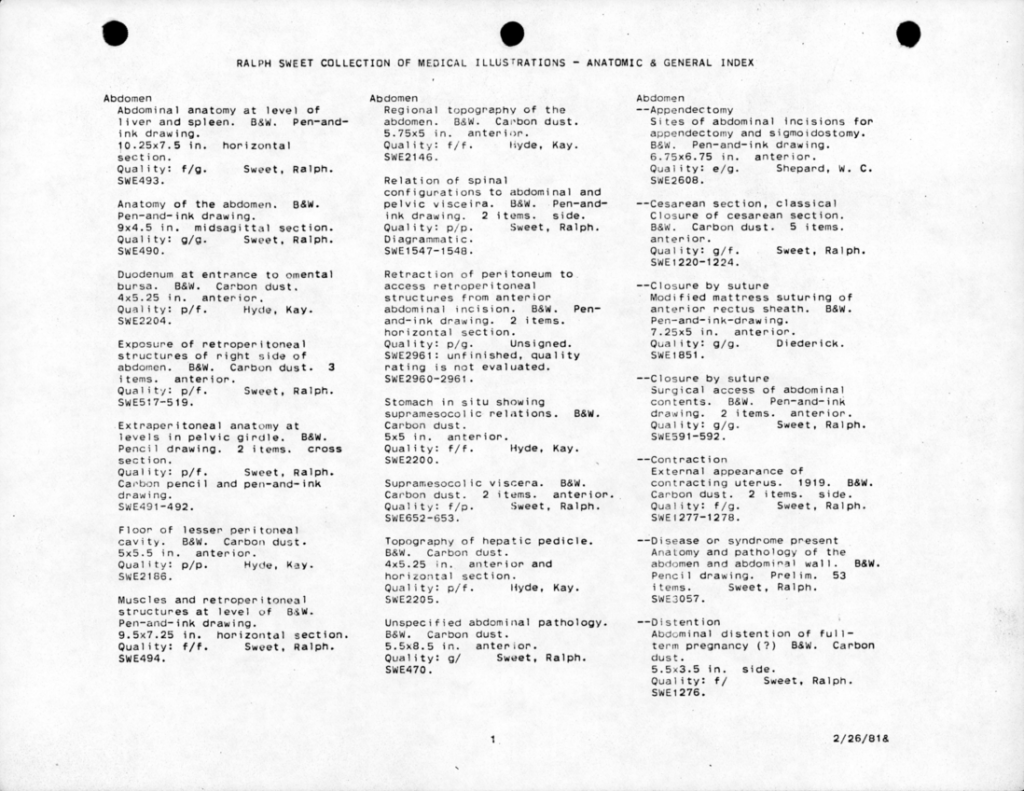

The Hoffinger papers contain information chronologically ranging from 1980 to 2006, topically from the concerns of nutrition on AIDS/HIV wasting syndrome, lipodystrophy, prescription medications, substance abuse, alternative medicine, steroids, protocols, and phosphatidylethanolamine drug combinations known as AL-721 and COQ. Hoffinger also included various publications including many AIDS Nutrition Services Association conference materials and presentations, industry and lay press publications, presentations, course syllabi, and patient handouts and publications. Her papers reflect more than twenty years of professional work in the interests of her patients. How future researchers use these materials is impossible to predict, but it is important that when they access this collection, they understand the role played by everyone involved in the collection, from Renée Hoffinger’s selection of materials to donate and UCSF’s willingness to preserve the papers, to a relatively inexperienced history Ph.D. student who helped process the collection and build the finding aid—the collection of metadata that helps researchers find useful materials within the archives—all played an important role in creating, processing, and preserving this information. If you are interested in this collection or others, you can visit the Renée Hoffinger papers at the UCSF Archives and Special Collections. I would also highly encourage anyone interested in the wealth of information available in this collection to provide feedback to the archivists about this collection or any others that you may explore. Would a certain keyword or phrase be useful to others if included on the finding aid? Did you encounter confidential information that was not flagged as such? Did the archives raise questions about potential gaps in the record? These things and others are useful bits of information that the archivists would appreciate.

The Anatomy of an Archive course in the Spring term of 2018 provided students with an invaluable insight into the behind-the-scenes processes of archival work. It helped us identify some professional blind spots and to think critically about archival data. It also helped us earn a profound appreciation for all the work that our archivists do for their fellow scholars and for their role in helping to create, not just preserve, the historical record. And if there is one invaluable piece of advice I can pass along, it is this: when starting your research, always ask an archivist for help. They know their archives better than anyone else and asking their advice will likely save hours of frustration and/or bear unforeseen fruits. And when you ask them for help, make sure to ask about the provenance of the collections you research. It will not only show that you appreciate their work but also provide you with invaluable information in how you approach your research.

Acknowledgements

This blog post was possible not only because it was a requirement on the syllabus, but because this course provided the author with a novel opportunity to peek behind the curtain. It is with the sincerest thanks to Dr. Aimee Medeiros and archivists Dr. Polina Ilieva, Kelsi Evans, and David Uhlich for making this experience possible and to Renée Hoffinger for being so indulgent with a graduate student’s questions. I would also like to extend appreciation to UCSF digital archivist Charlie Macquarie and Dr. Mario Ramirez of Indiana University for taking the time to join our seminar session discussions and to the members of the Archivists and Librarians in the History of Health Sciences association for so warmly welcoming a historian like me among their ranks. I will endeavor to do for my students what all of you have done for me. Thank you.

Join us on June 20th from 12-2pm in the UCSF Library Makers Lab for Do-It-Yourself Archiving! The UCSF Archives staff will provide supplies and instruction on how to preserve and organize your personal records. Participants are encouraged to bring in material they want to archive, like photograph albums, childhood drawings, early writings or research, even love letters! The UCSF Digital Archivist will also be on hand to provide tips on managing your personal digital archive.

Join us on June 20th from 12-2pm in the UCSF Library Makers Lab for Do-It-Yourself Archiving! The UCSF Archives staff will provide supplies and instruction on how to preserve and organize your personal records. Participants are encouraged to bring in material they want to archive, like photograph albums, childhood drawings, early writings or research, even love letters! The UCSF Digital Archivist will also be on hand to provide tips on managing your personal digital archive.