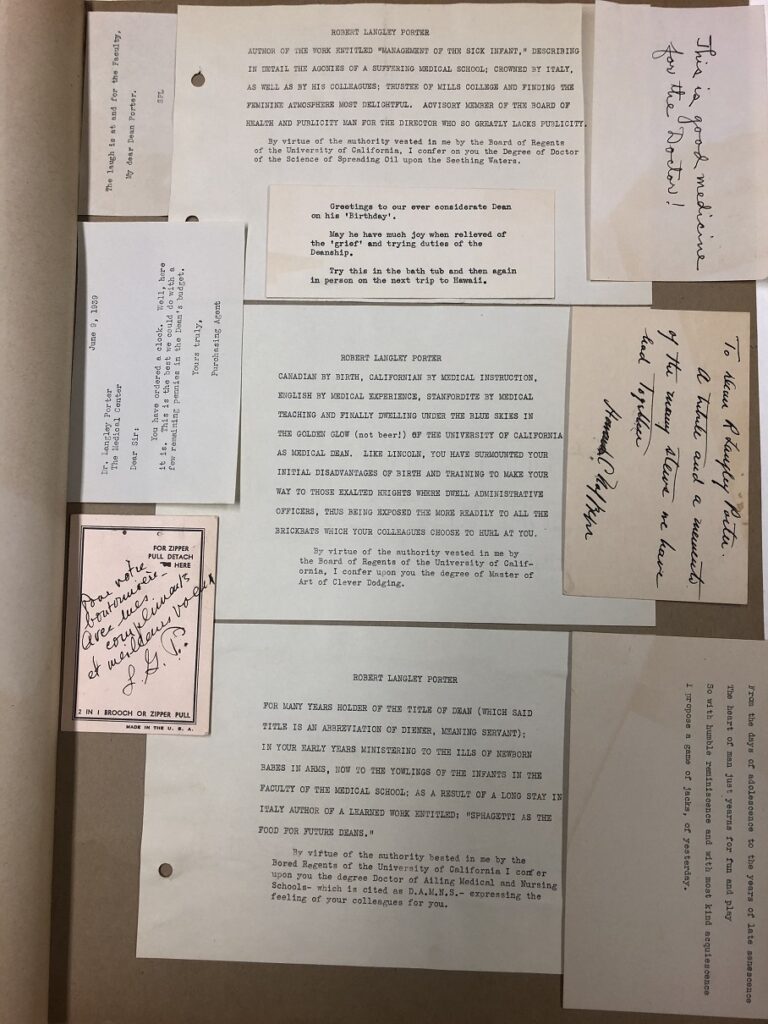

This is a guest post by Aaron J. Jackson, PhD student, UCSF Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine.

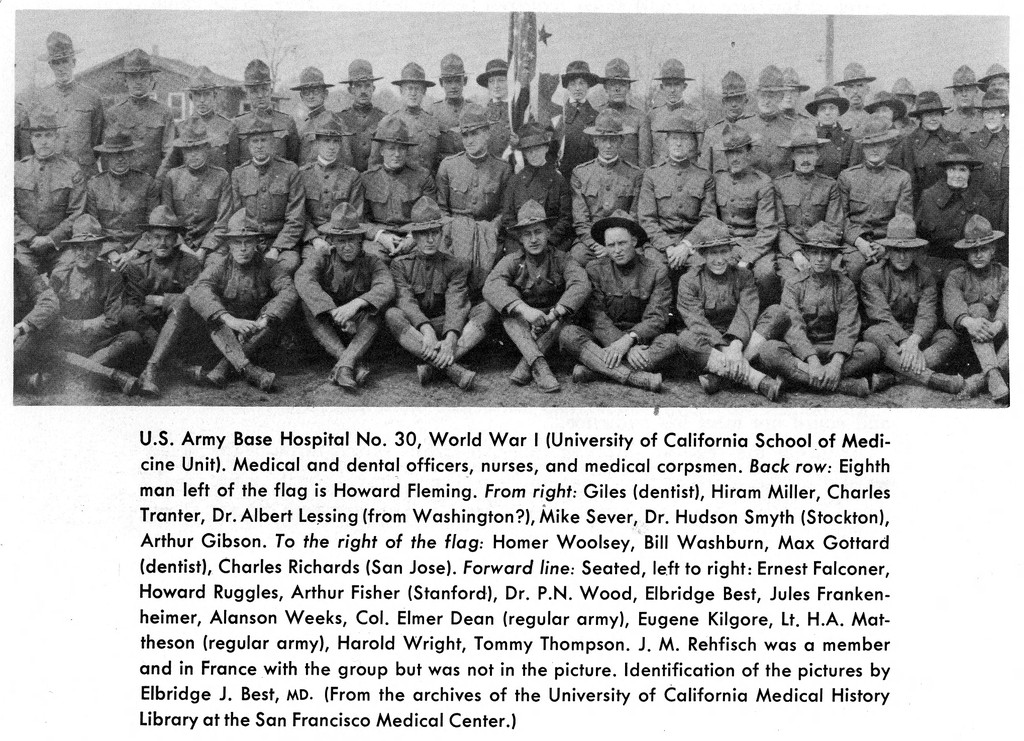

One hundred years ago today, April 24, 1918, the 240 men and women of U.S. Army Base Hospital No. 30—the University of California School of Medicine Unit—left American soil to support the war effort by operating a modern hospital in France. Their stories survive in the UCSF Archives and Special Collections, where they contribute to the rich history of the UCSF and San Francisco communities. In this four-part series, I hope to introduce you to the stories of the men and women of Base Hospital No. 30, and I encourage you to learn more by visiting the UCSF Archives and Special Collections in the Parnassus Library.

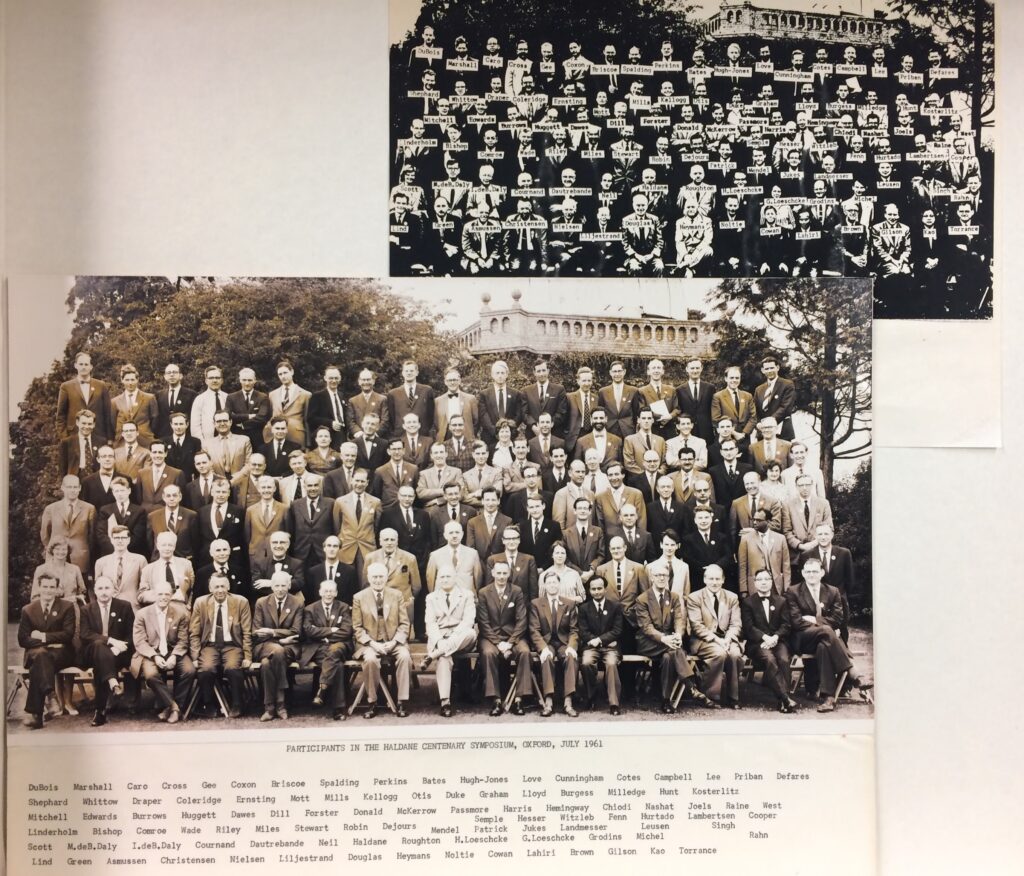

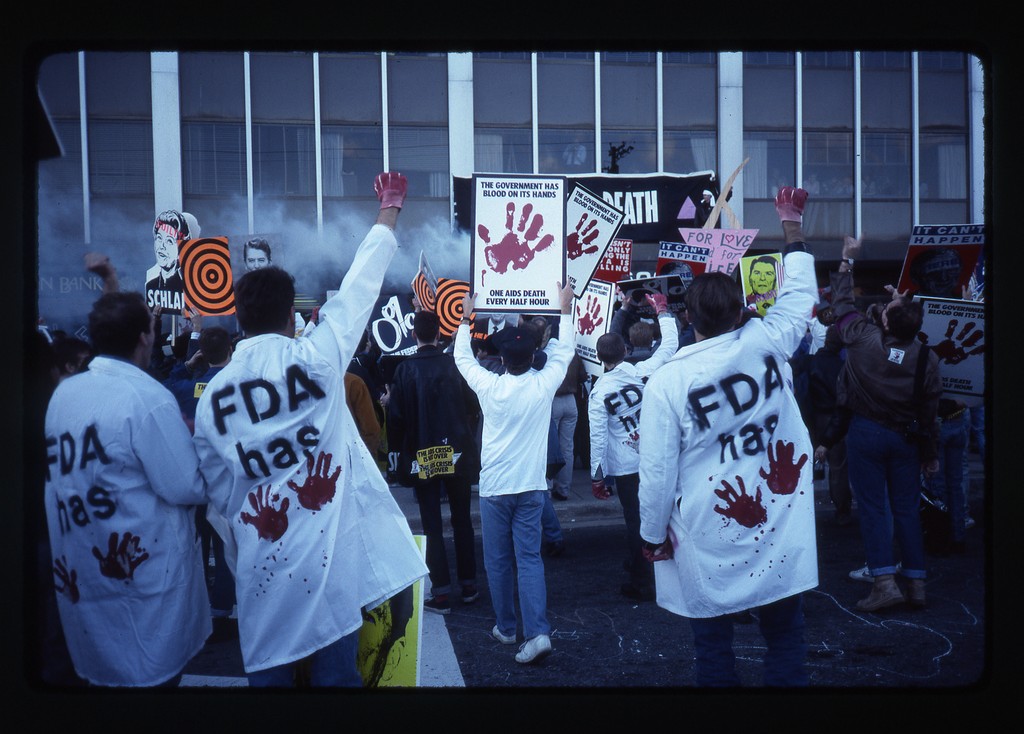

Figure 1 – U.S. Army Base Hospital No. 30, World War I

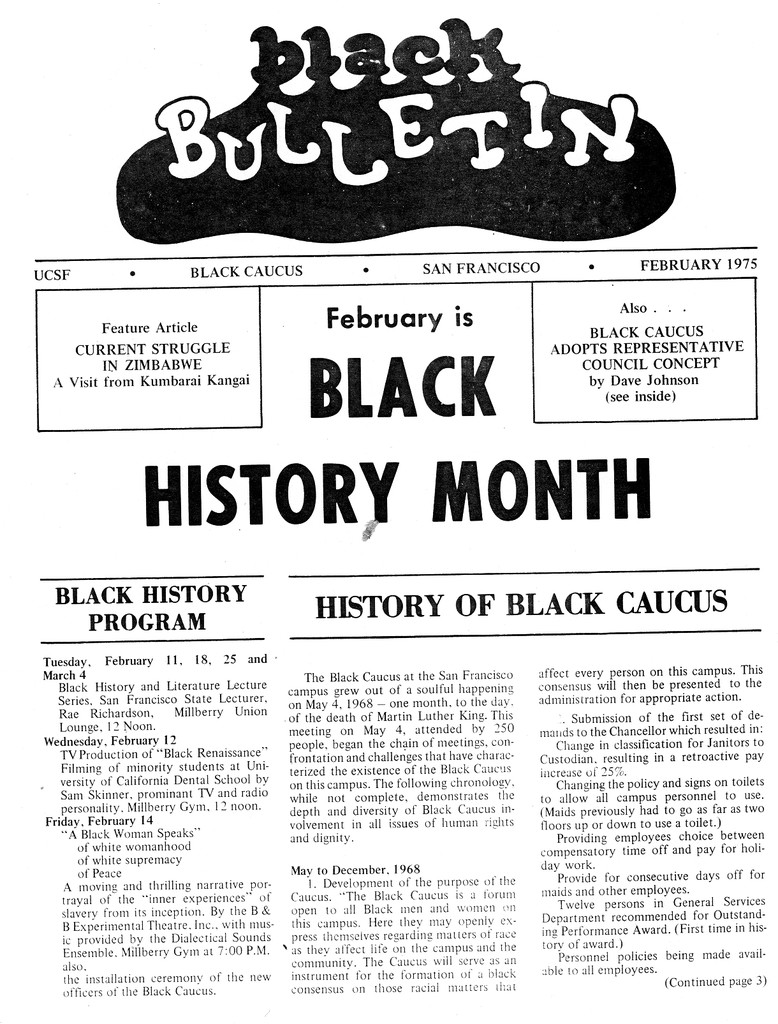

“This book purports to be a record, not merely of the happenings and the activities of Base Hospital Number Thirty, but a permanent record of the personnel with the addresses, that we may always keep in touch with one another and thus preserve the bonds of friendship now existent among us.” – Foreword, The Record

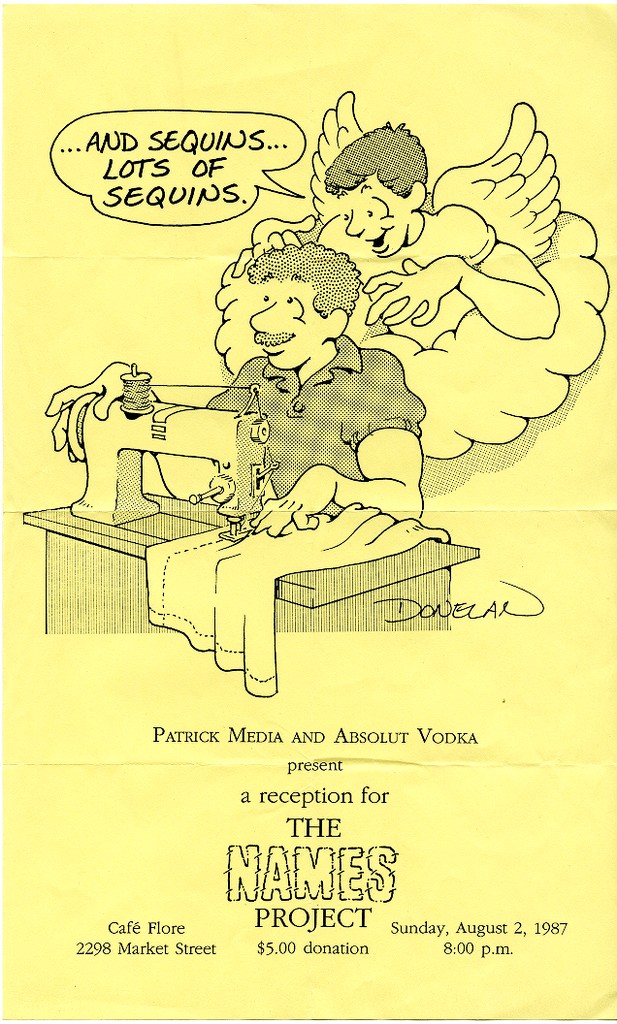

As the foreword to the book they commissioned to commemorate their experience expresses, the men and women of Base Hospital No. 30 formed a tight-knit community during their time in the service in the First World War. When Congress declared war on Germany on April 4, 1917, the American Red Cross Society quickly set to work in establishing, organizing, and supplying medical units in the nation’s leading medical institutions with the intent of creating a system of hospitals in France to treat the inevitable casualties of the war. The American medical community was enthusiastic about the effort. Famed surgeons George Crile and Harvey Cushing had been working with America’s French and British allies since 1915 to establish new medical techniques and organizational methods. Many physicians viewed the war as an opportunity to advance medical knowledge while simultaneously serving their country, and many members of the University of California Department of Medicine felt the same. With the assistance of the Red Cross, Base Hospital No. 30 began to organize in the spring and early summer of 1917. Consisting roughly of twenty-five officers, sixty-five nurses, and one-hundred-fifty enlisted men, the unit marched down Market Street as part of a Liberty Loan parade to raise money for the base hospital and to support the war effort.

Figure 2 – Liberty Loan Parade, San Francisco, Cal.

Unfortunately, the initial excitement of the spring and early summer became a period of uneasy waiting and bureaucratic frustration that dragged into the fall as the unit waited on official orders to arrive. Many members of the unit, including one or two officers and several of the nurses and enlisted men, anticipating immediate entrance into the service, had packed and stored their belongings and quit their jobs, and the commanding officers had to continuously combat rumors that the organization had been broken up or that no more base hospitals would be sent to France. Thankfully, the Red Cross had managed to secure $100,000 in funding, which it used to collect supplies while the Army bureaucracy plodded along. Finally, on November 20, 1917, Base Hospital No. 30 received official orders to muster at Fort Mason in San Francisco.

While the unit drilled and trained in the operation of a military hospital, the nurses received separate orders to travel to New York. They were able to enjoy the Christmas holiday with their friends and family before taking their oath of service at the Presidio on December 26, 1917 and setting out on a five-day, frigid train ride to New York City. They arrived on New Year’s Day and spent the next three weeks on Ellis Island preparing their uniforms and equipment and receiving training. On January 25, they were divided into five groups bound for Army camps in South Carolina, Maryland, Ohio, Georgia, and Virginia, where soldiers gathering from across the nation were coming down with acute infections like measles and mumps in large numbers. While the nurses expressed disappointment at not being able to set out for France immediately, Chief Nurse Arabella Lombard expressed that they were happy to be of service and to gain valuable experience before receiving orders to return to New York in March.

Figure 3 – Nurses of Base Hospital No. 30

Back in San Francisco, the officers spent their time working at clinics in the city and training the enlisted personnel. On March 3, 1918, nearly a year after the declaration of war, the unit received orders to pack their supplies and board the steamship S.S. Northern Pacific en route to New York. The trip took two weeks—a near-record pace at the time—and the unit was assigned temporary barracks at Camp Merritt. While in New York, several of the officers attended clinics on the latest medical techniques, such as instruction on the treatment of pneumonia and meningitis at the Rockefeller Institute and the Carrel-Dakin course on aseptic surgery and wound treatment—essentially the use of diluted chlorine and bleach solution to hasten the separation of dead from living tissue, which was cutting-edge lifesaving technology before the discovery of antibiotics.

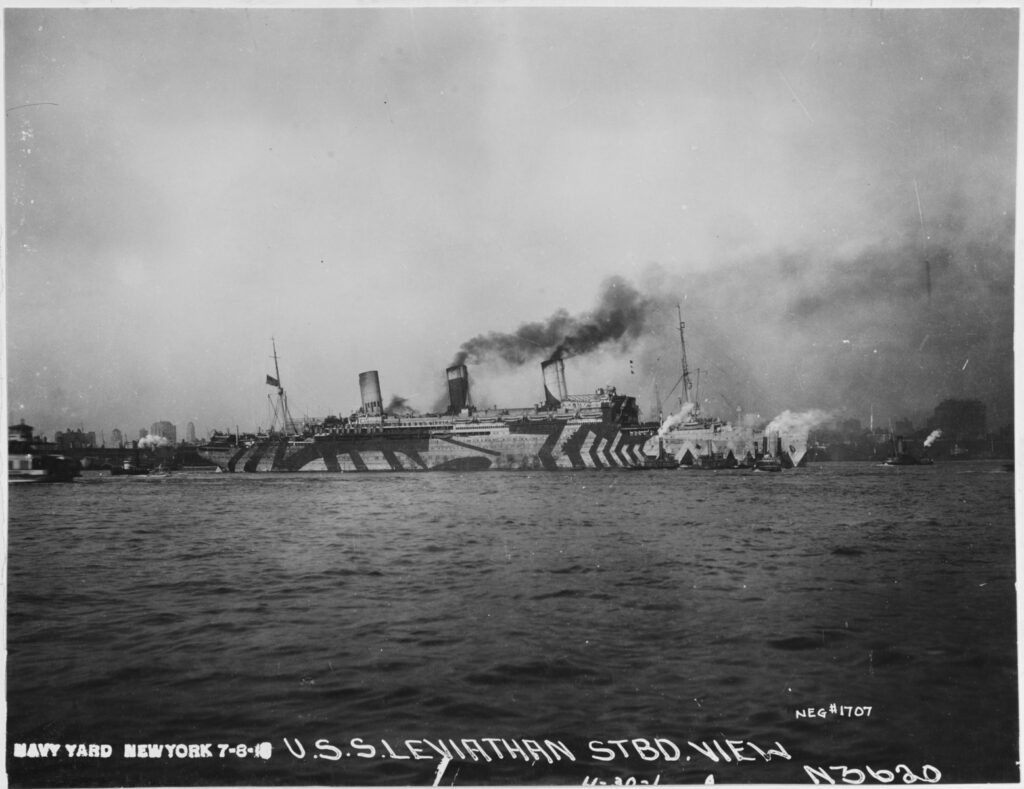

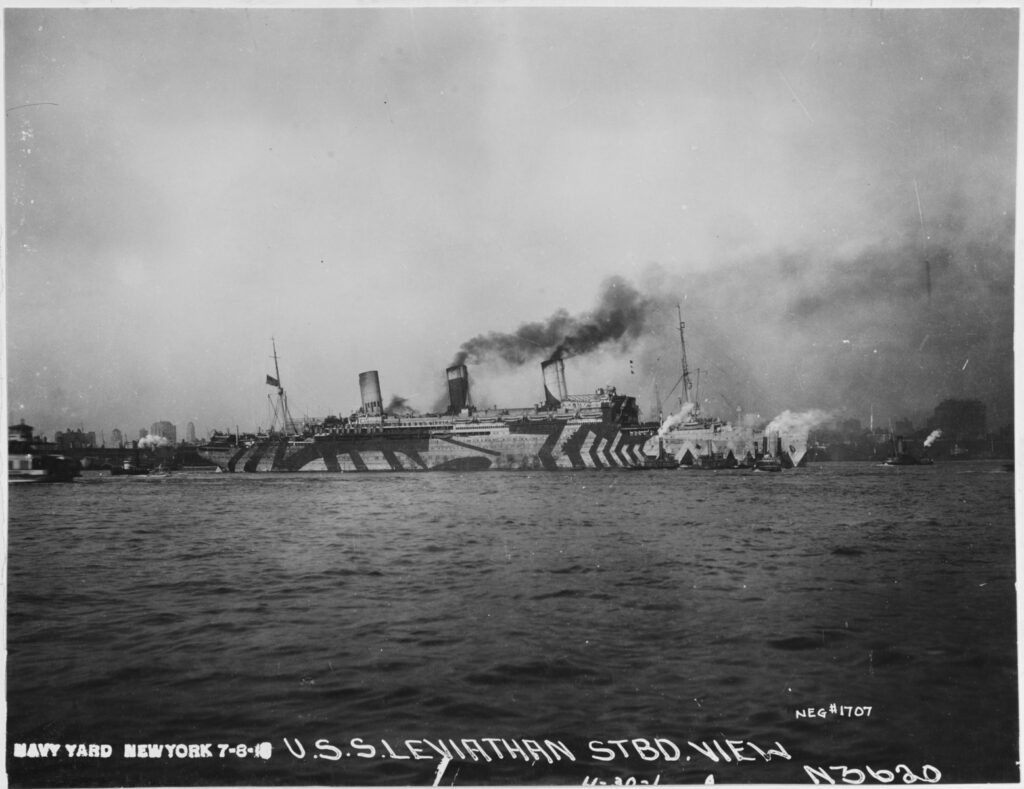

On April 22, the nurses rejoined Base Hospital No. 30 as the unit boarded the U.S.S. Leviathan, a former German luxury liner originally named the Vaterland that had been seized by the U.S. government the year prior and converted into a troopship. They set sail on April 24, 1918. More than one year after Congress’s declaration of war on Germany, the members of Base Hospital No. 30 were finally travelling to France. They anticipated the hard but meaningful work of repairing the broken bodies of America’s soldiers, but in France, they would have to overcome a number of unexpected obstacles before that work could take place.

Click here to read Part Two of the series.

Figure 4 – USS Leviathan

Figures:

1 – “U.S. Army Base Hospital No. 30, World War I,” circa 1917, UC San Francisco, Library, University Archives, Base Hospital #30 Collection.

2 – “Liberty Loan Parade, San Francisco, Cal.,” circa 1917, California State Library, California History Section Picture Catalog.

3 – “Nurses of Base Hospital No. 30,” January 1918, UC San Francisco, Library, University Archives, Base Hospital #30 Collection.

4 – “USS Leviathan,” 8 July 1918, Naval History & Heritage Command, 19-N-1707.

Join us on June 20th from 12-2pm in the UCSF Library Makers Lab for Do-It-Yourself Archiving! The UCSF Archives staff will provide supplies and instruction on how to preserve and organize your personal records. Participants are encouraged to bring in material they want to archive, like photograph albums, childhood drawings, early writings or research, even love letters! The UCSF Digital Archivist will also be on hand to provide tips on managing your personal digital archive.

Join us on June 20th from 12-2pm in the UCSF Library Makers Lab for Do-It-Yourself Archiving! The UCSF Archives staff will provide supplies and instruction on how to preserve and organize your personal records. Participants are encouraged to bring in material they want to archive, like photograph albums, childhood drawings, early writings or research, even love letters! The UCSF Digital Archivist will also be on hand to provide tips on managing your personal digital archive.