Guest post by Manami Yasui, Manami is a professor at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies, Kyoto, Japan and guest curator for the exhibition “Maternal Health and Images of the Body in Japanese Ukiyo-e.“

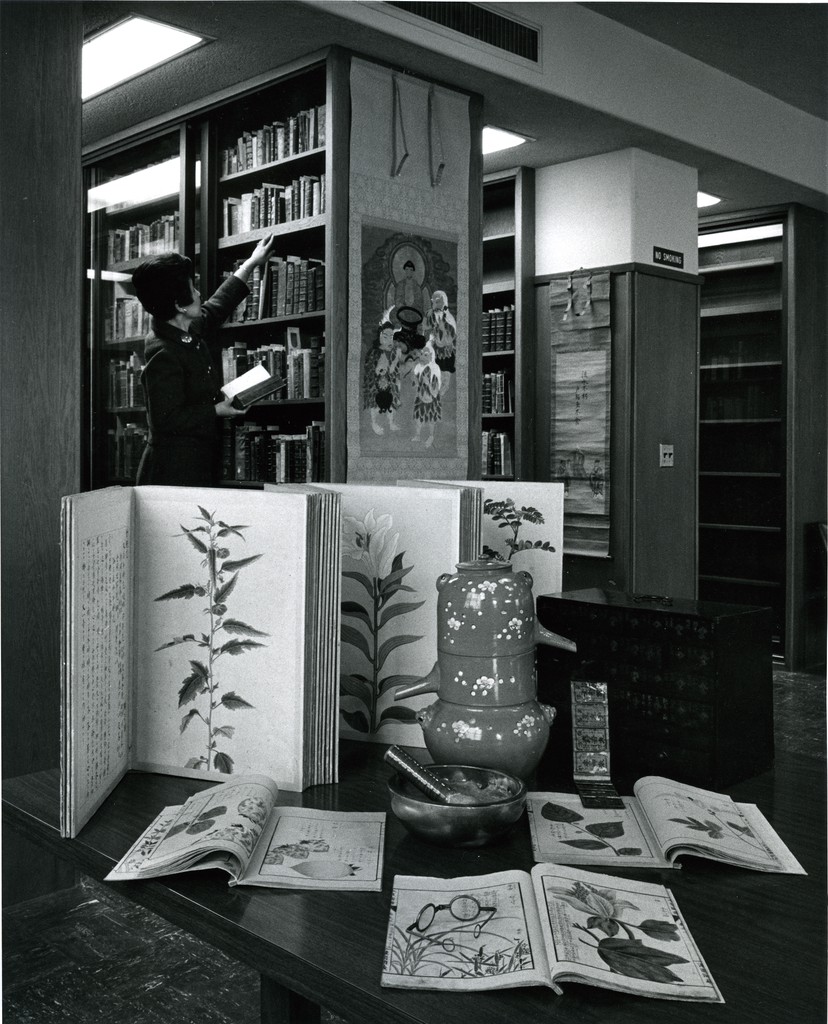

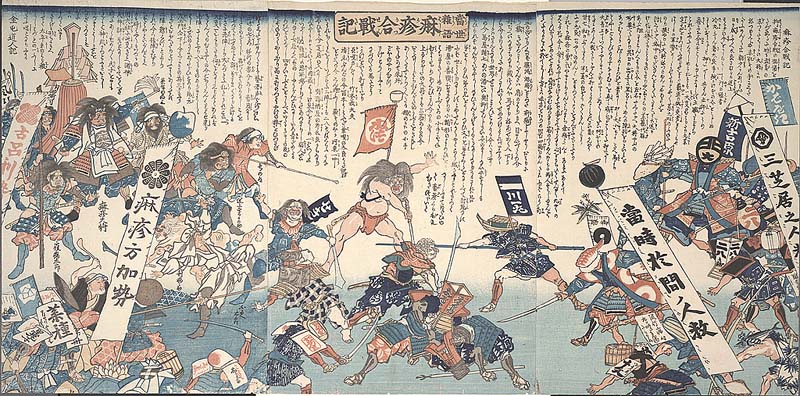

We are pleased to announce the new exhibition, “Maternal Health and Images of the Body in Japanese Ukiyo-e,” which will be on view on the main floor of the UCSF Kalmanovitz Library at Parnassus Heights from November 2023 through December 2024. This exhibition explores the historical perspectives surrounding the human body and maternal health in Japan through the lens of ukiyo-e woodblock prints and paintings.

The central question driving our selection of images, most of which come from the UCSF Japanese Woodblock Print Collection and the International Research Center for Japanese Studies (Nichibunken) collection, is how was the human body represented in mid-19th-century Japan? Ukiyo-e is a genre of Japanese graphic art popularized from the 17th through the 19th-centuries. The exhibition uses a selection of ukiyo-e works and other artifacts from the 1820s to the 1880s. By drawing on various visual arts and medical media, we explore pregnancy and childbirth in early modern Japan and how birth control methods such as abortion and mabiki (infanticide or “thinning out”) were viewed at the time.

Depictions of pregnancy and the fetus

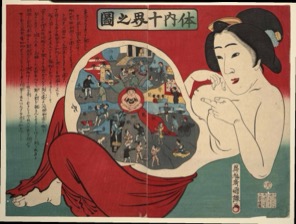

One important representation of the early modern epistemology of the human body from a Japanese lens is seen in this fascinating ukiyo-e print entitled the “Ten Realms within the Body” 体内十界之圖, 1885 by Utagawa Kuniteru III 歌川国輝(三代)(active ca. 1877-1896).

This print depicts a Japanese woman wearing only an underskirt. She appears to be pregnant and is pointing at her ample abdomen. The interior of her abdomen depicts a series of scenes likened to a Buddhist mandala. The image is likely a parody of the famed “Ten Realms Mandala” (jp. Kanjin jukkai zu), which illustrates the ten states of Buddhist existence surrounding a central “heart” character. Of the ten realms, the upper five represent enlightened states, while the lower half includes one realm representing humanity and the remaining four realms representing “lesser beings,” such as demons or animals. Kuniteru’s version maintains a similar balance with each “realm” by representing facets of human society; however, this version connects Buddhist beliefs with the understandings of pregnancy and life choices during Kuniteru’s time.

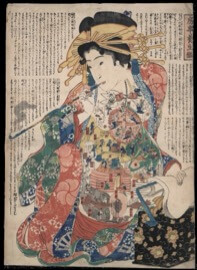

Putting the interior of the human body on display was one of the hallmarks of visual media during this period. People were interested in the invisible interior of the human body, and the ukiyo-e of the time responded to their desire to peer inside. Another popular set of prints depicts ten pregnant women, each with a fetus at a different stage of growth. While Western medical science measures the length of a full-term pregnancy at nine months (40 weeks), in early modern Japan, a full-term pregnancy was calculated according to the lunar calendar, and was divided into ten four-week periods. This explains why the women depicted in the ukiyo-e, “Realize One’s Parental Love” 父母の恩を知る図, 1880, Utagawa Yoshitora 歌川芳虎 depicts ten stages of growth.

The Chinese (Sinitic) medical body

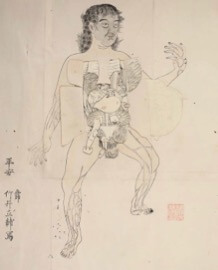

At the same time, the human body in early modern Japan reflected a worldview grounded in Chinese (Sinitic) medical thought. This system classifies organs as consisting of “five viscera and six entrails.” The above print contains advice on conducting one’s sex life through the then-popular mode of “nourishing health” (yōjō), with detailed explanations on important reproductive organs such as the uterus. The small figures within each organ represent the constant motion and labor that each organ undertakes to keep the body functioning.

The introduction of Western anatomy to Japan

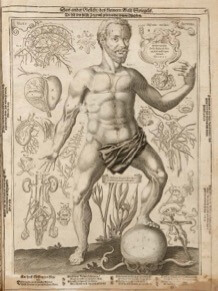

While most medical depictions of the body in early modern Japan were informed by Chinese (Sinitic) medicine, European anatomy books, many published in Dutch editions, were imported by Dutch merchants into the port of Dejima in Nagasaki, Kyushu, which was built in 1636. One example was “Remmelin’s Catoptrum Microcosmicum” (1619), which was introduced to Japan via its Dutch version, “Pinax Microcosmographicus” (1667). The book publishers painstakingly printed organs on small flaps of paper that are then layered on top of one another. This book attempted to illustrate holistically male and female bodies, and the inner organs in detail. When the reader flips open the layer depicting the womb, an image of a fetus appears.

In this exhibition, you can compare both Remmelin’s original (UCSF Archives and Special Collections, 1619) and the Japanese translated edition (Nichibunken collection, 1772). We have also replicated the female body image from the Japanese translation for the exhibition. This provides visitors with a hands-on experience of “exploring” the text by “opening” the abdomen and “removing” the internal organs of the body.

We encourage you to enjoy these diverse images of pregnancy, childbirth, and bodily images from Japan’s Edo period (1603 -1868). We hope viewers will gain a better understanding of early modern Japanese practices around the body, and maternal health, including abortion and mabiki. Along with the UCSF Kalmanovitz Library exhibition, we are also planning to offer online exhibitions in Japanese, English, and Chinese. Please stay tuned for further information.

Exhibition opening reception

We invite the UCSF community and members of the public to attend our opening reception Wednesday, November 1, 2023, from 4 to 5:30 p.m. at the UCSF Kalmanovitz Library (Parnassus Heights). Admission is free and open to the public. Light refreshments will be provided while supplies last.

Please register by Friday, October 31, 2023.

本木了意訳、鈴木宗云撰次Motoki Ryōi, trans (c. 1682), Suzuki Shūun, ed.

Acknowledgements

The exhibition, Maternal Health and Images of the Body in Japanese Ukiyo-e, is a collaboration between the University of California, San Francisco Archives and Special Collections and the International Research Center for Japanese Studies. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the collaborators listed below and the many other colleagues who made this exhibition possible.

International Research Center for Japanese Studies

- Manami Yasui, PhD, guest curator

Nichibunken Project Team

- Lawrence Marceau, Noriko Itasaka, Lee I Zhuen Clarence, Michaela Kelly, Chihiro Saka, Hiroshi Fujioka, Ayako Ono, and Yoko Sakai

University of California, San Francisco Library

- Polina Ilieva, Associate University Librarian for Collections and University Archivist

UCSF Project Team

- Peggy Tran-Le, Kirk Hudson, and Jessica Crosby

With special thanks to

- Stephen Roddy, University of San Francisco

- Mark McGowan, exhibition graphic designer

Feature image credit: “Realize One’s Parental Love” 父母の恩を知る図, 1880. Utagawa, Yoshitora歌川芳虎, courtesy of the UCSF Archives and Special Collections.