The UCSF Library Archives and Special Collections is pleased to announce the digitization of the Carol Hardgrove papers and the Hulda Evelyn Thelander papers. The digitization of the collections is part of our current grant project, Pioneering Child Studies: Digitizing and Providing Access to Collection of Women Physicians who Spearheaded Behavioral and Developmental Pediatrics, supported by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC). The grant supports the creation of digital collections on Calisphere containing materials from five collections held at UCSF. These collections document the life and work of five women physicians and social workers. The finding aids for theses collections are available publicly on the Online Archive of California.

Carol Hardgrove

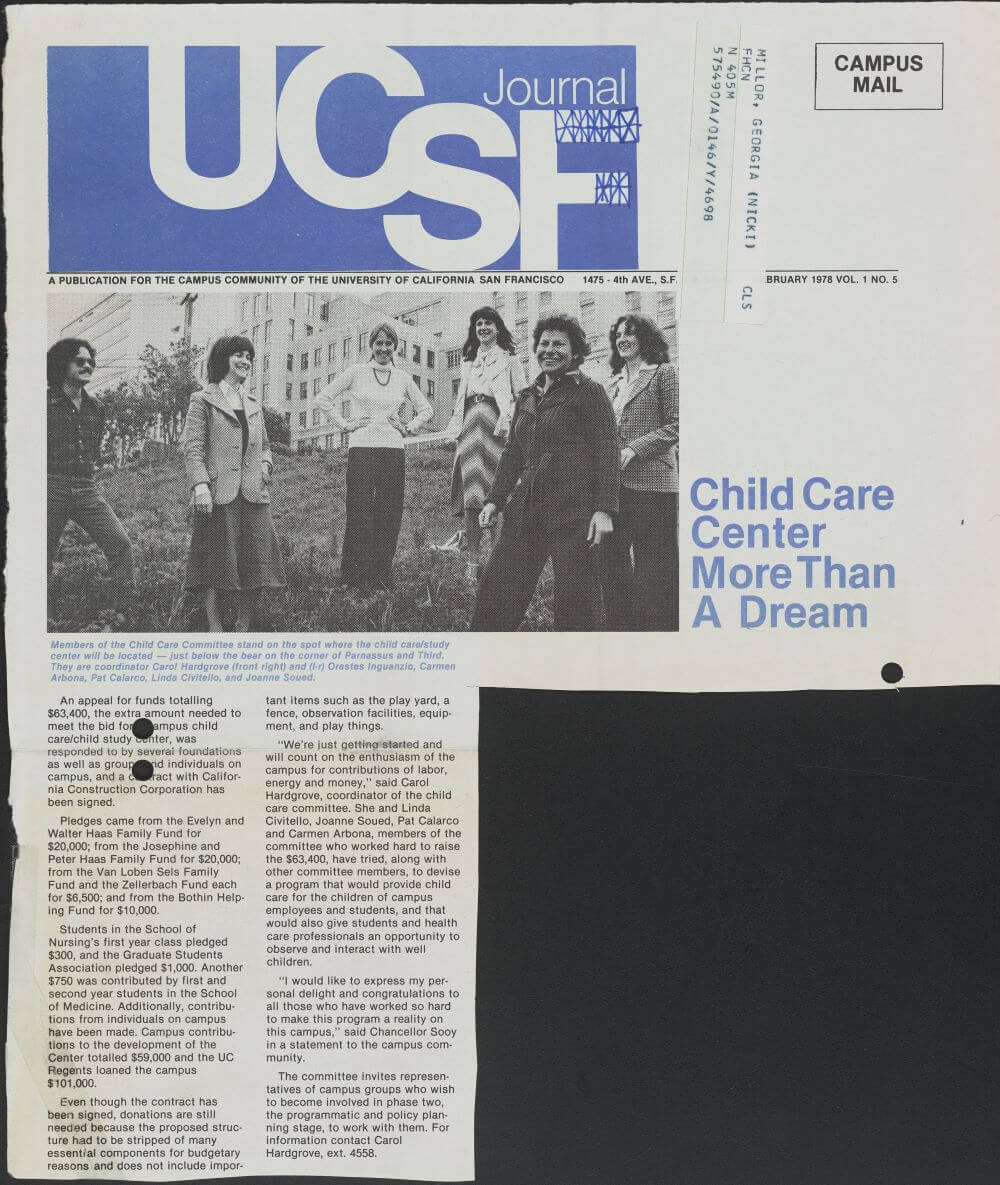

Carol Hardgrove worked in several nursery and childcare centers and was an educational consultant for Project Head Start from 1966 to 1970. The collection includes correspondence, published and unpublished manuscripts, photographs, and secondary materials on her subjects of interest. One of the items in the collection is an essay, “Play in the Day Care Center” which was written by Mrs. Hardgrove on the interpretation of the word “play”. She writes, “Play means different things to different people; serves different purposes at different stages of development. Play is to the infant, the toddler, and the preschooler the life breath of childhood; the force that carries into experiences of reasoning, relating, rehearsing, and researching. Through play, the child works to understand, to master, to integrate, to try on different roles in fantasy. Children learn through play.”

Another item in the collection is a travel study report called “Parent Participation and Play Programs in Hospital Pediatrics in England, Sweden, and Denmark,” granted by the World Health Organization. She shares her experience in Europe and meeting parents, patients, nurses, psychologists, and physicians. She writes, “I truly learned the meaning of “hands across the sea,” and hope that together, we may continue to work to improve the situation for young hospitalized children and their families.”

Hulda Evelyn Thelander

Hulda Evelyn Thelander, MD, interned at Children’s Hospital in San Francisco, and later became the pediatrics department chief in 1951. During WWII she was a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Navy, retiring as commander and serving as Chief Consultant for Women Veterans, Western Area. Dr. Thelander founded the Child Development Center at Children’s Hospital in 1952 and conducted studies on children with traumatic brain injuries and general pediatric neurology. The papers in this collection consist in large part of correspondence (many with friends and family members), diaries, memoirs, travel accounts, some medical manuscripts and research notes. Several newspaper articles were written about Dr. Thelander praising her hard work helping children with disabilities. She wrote an essay on the history of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital called “The Department of Pediatrics of Children’s Hospital“. She also wrote several guides to inform parents and the community about children with physical disabilities.

From 1967 – 1971, Dr. Thelander attended medical school for a second time. It had been 40 years since she graduated with her medical degree from the University of Minnesota. She kept a diary about her experience returning to medical school at UCSF. Additionally, in 1971 she received a special citation from the Gold Headed Cane Society completing medical school a second time.

More to come

Next month we will digitize our last two collections of this project and publish them on Calisphere. Stay tuned for our next update.