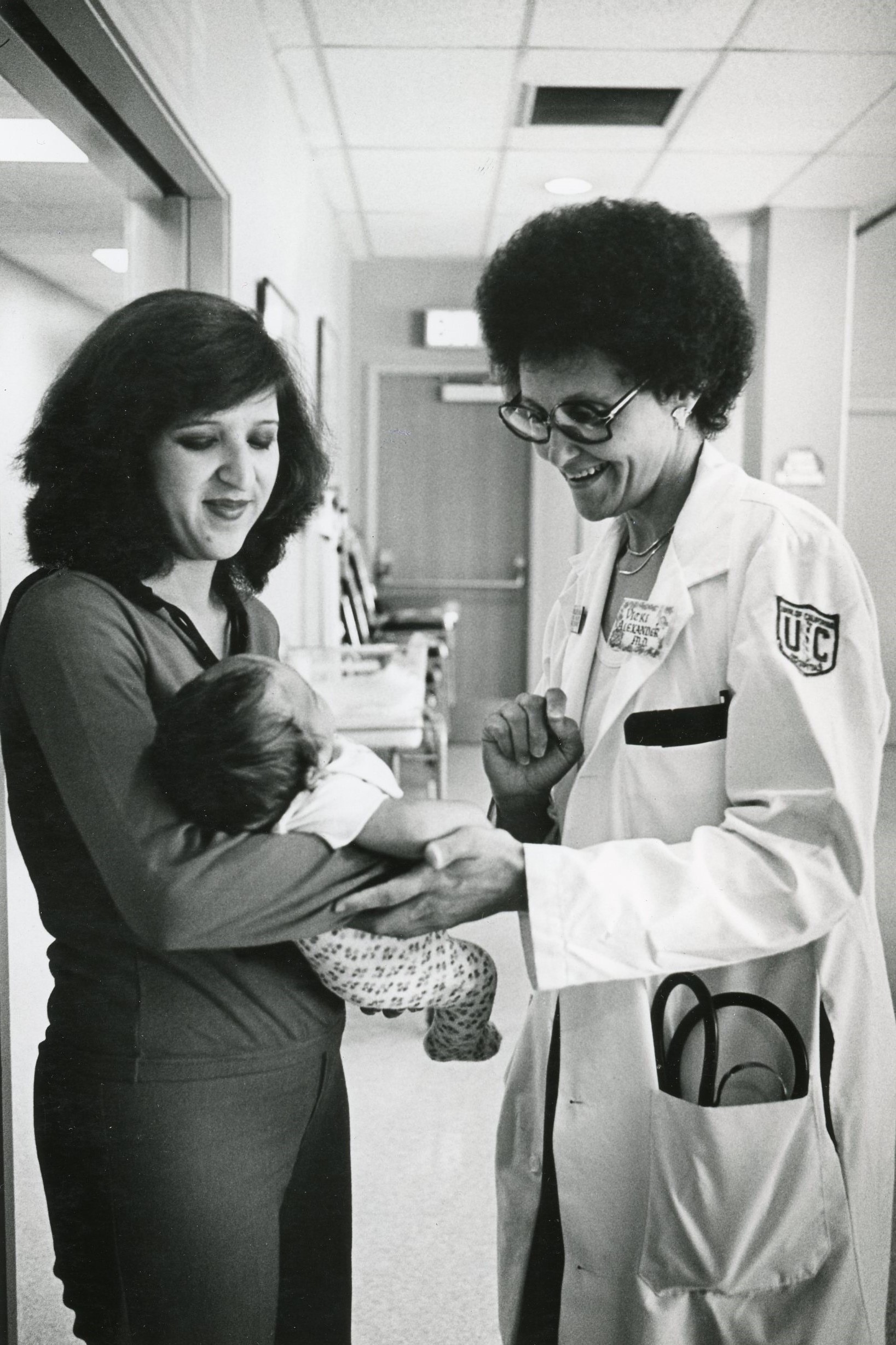

Vicki Alexander, MD, has dedicated her life to improving the social determinants of public health.

Alexander attended the UC San Francisco, where she completed her medical degree and residency in Obstetrics and Gynecology in 1974. She went on to Columbia University, where she obtained her master’s degree in Public Health.

Dr. Alexander began as an Ob-Gyn Clinical Instructor at San Francisco General Hospital. She soon became the director of SFGH’s Perinatal Health Project, which served high-risk mothers and infants in the community. Alexander then relocated to New York, working as a clinical instructor and chief of obstetrics and gynecology at Harlem Hospital. Eventually, she returned to the west coast and became the Maternal Child Health Director and Health Officer for the City of Berkeley until she retired in 2006.

Alexander has participated in many organizations to improve the living conditions for women and children, including: Rainbow Coalition, Center for Constitutional Rights, Reproductive Rights National Network, Planned Parenthood, City Material and Child Health.

In 1978, she established the Coalition to Fight Infant Mortality in Oakland, which helped women with medical care and social issues.

In 2000, Alexander began the Black Infant Health program in Berkeley, which grew from her coalition at Highland Hospital. This was the foundational step to the creation of the Alameda County Coalition to decrease infant mortality.

Alexander is also the current founder and board president of Healthy Black Families (HBF), Inc., which dovetails with the Black Infant Health program. It was founded as a non-profit organization in July 2013 to support the health, growth, development, and future of Black individuals and families.

For her devotion towards health and social justice, Dr. Vicki has won many awards, including: Women of the Year Award (2011); Martin Luther King, Lifetime Achievement Award (2014); National Jefferson Award for Community Service (2015); Alameda County African American Black History Month Award (2017); Madame CJ Walker Award for Black Women (2017); and 15th Assembly District Woman of the Year Award (2017).

To learn more about Dr. Vicki, check out these articles available in our digital collection on HathiTrust and Synapse Archive:

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.31378005703288&view=plaintext&seq=173

https://synapse.library.ucsf.edu/?a=d&d=ucsf19791004-01.2.3&srpos=3&e=——-en–20–1–txt-%22vicki+alexander%22—–txIN–

https://synapse.library.ucsf.edu/?a=d&d=ucsf19800605-01.2.2&srpos=4&e=——-en–20–1–txt-%22vicki+alexander%22—–txIN–

*Authored by Jazmin Dew*