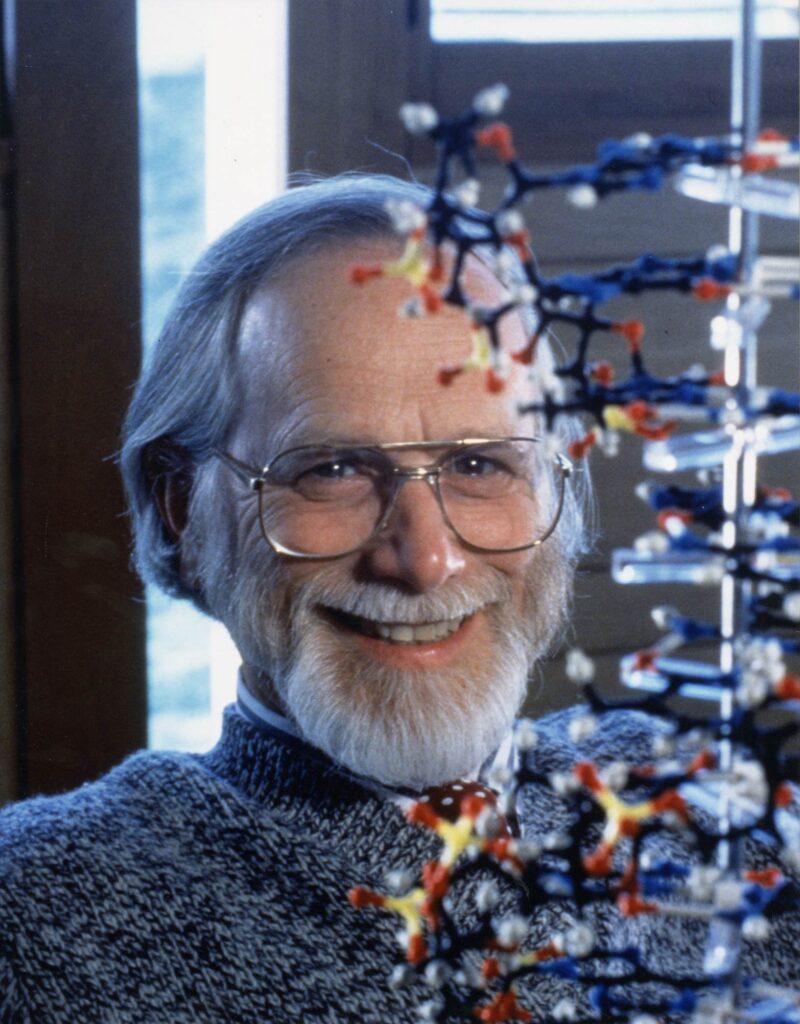

We are pleased to announce that the J. Michael Bishop Papers digital collection is now available publicly on Calisphere.org. Bishop is a Nobel Prize-winning researcher and UCSF Chancellor Emeritus. The digital collection features hundreds of pages of material and photographs selected from Bishop’s papers housed in the UCSF Archives and Special Collections (MSS 2007-21).

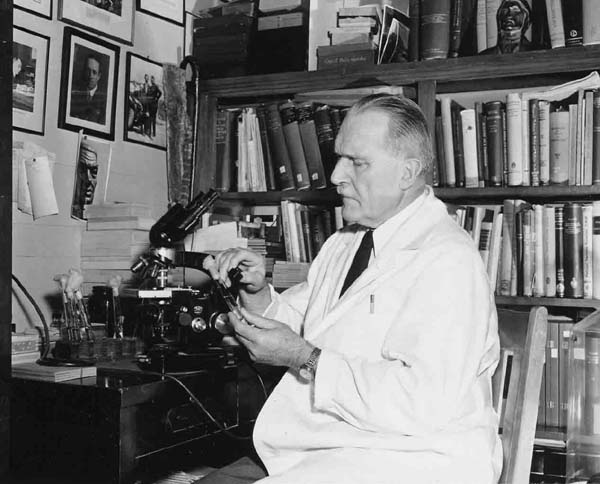

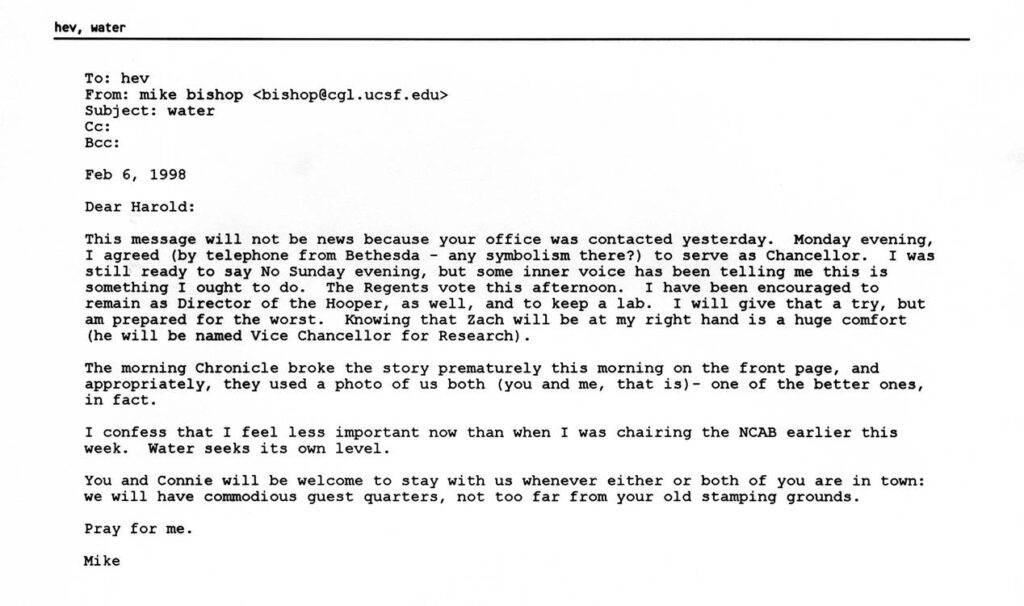

J. Michael Bishop, MD, joined the UCSF faculty in 1968. He was appointed director of the GW Hooper Research Foundation in 1981 and named UCSF Chancellor in 1998, a post he held until 2009. He continues to serve as Hooper’s director and as professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology.

J. Michael Bishop email to Harold Varmus regarding Bishop’s University of California, San Francisco Chancellor appointment, 1998-02-06. MSS 2007-21, carton 18, folder 43.

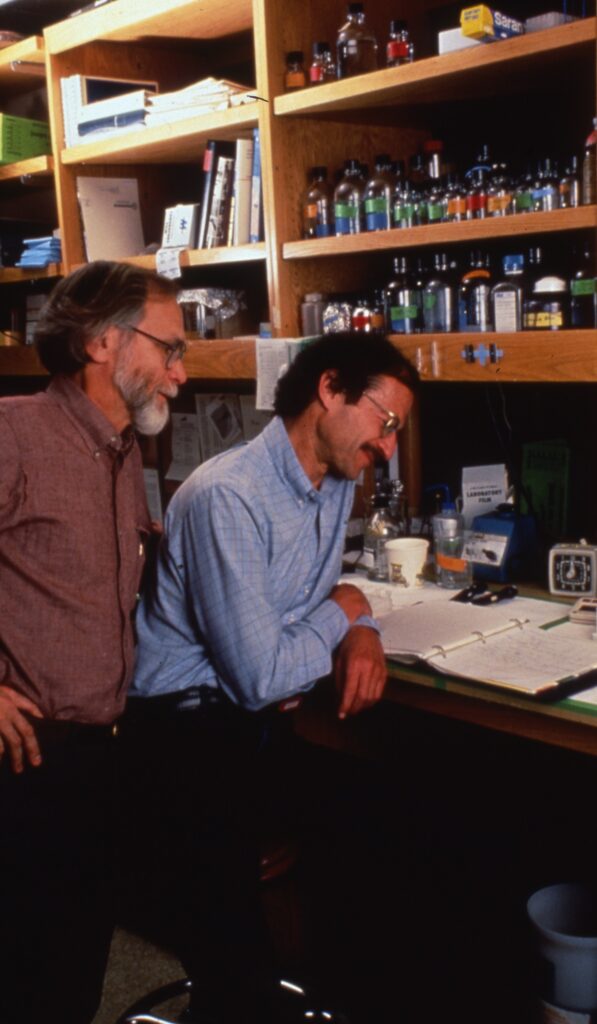

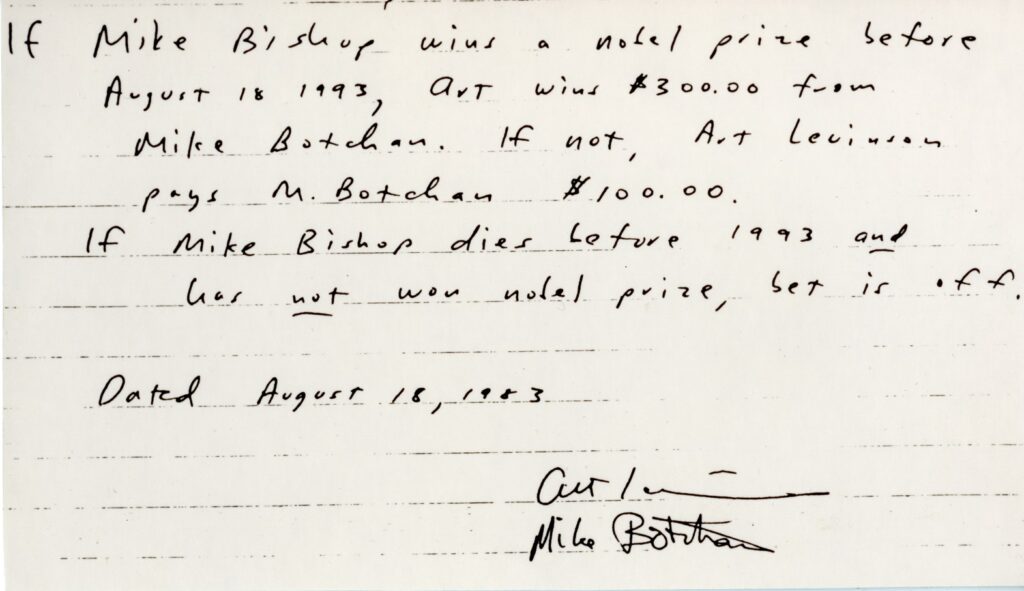

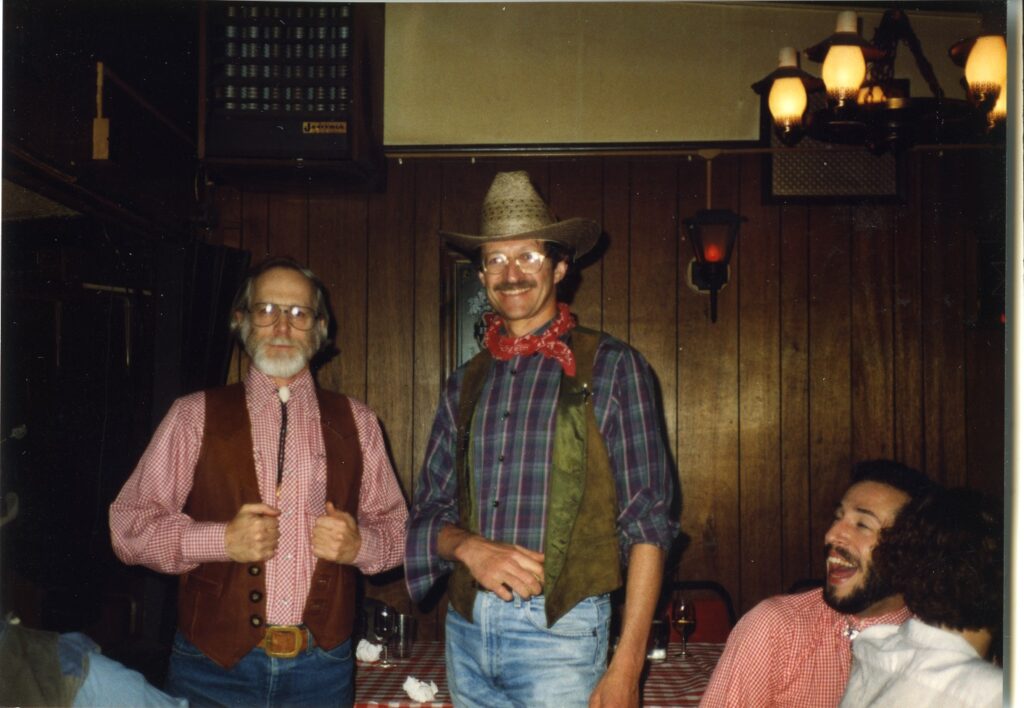

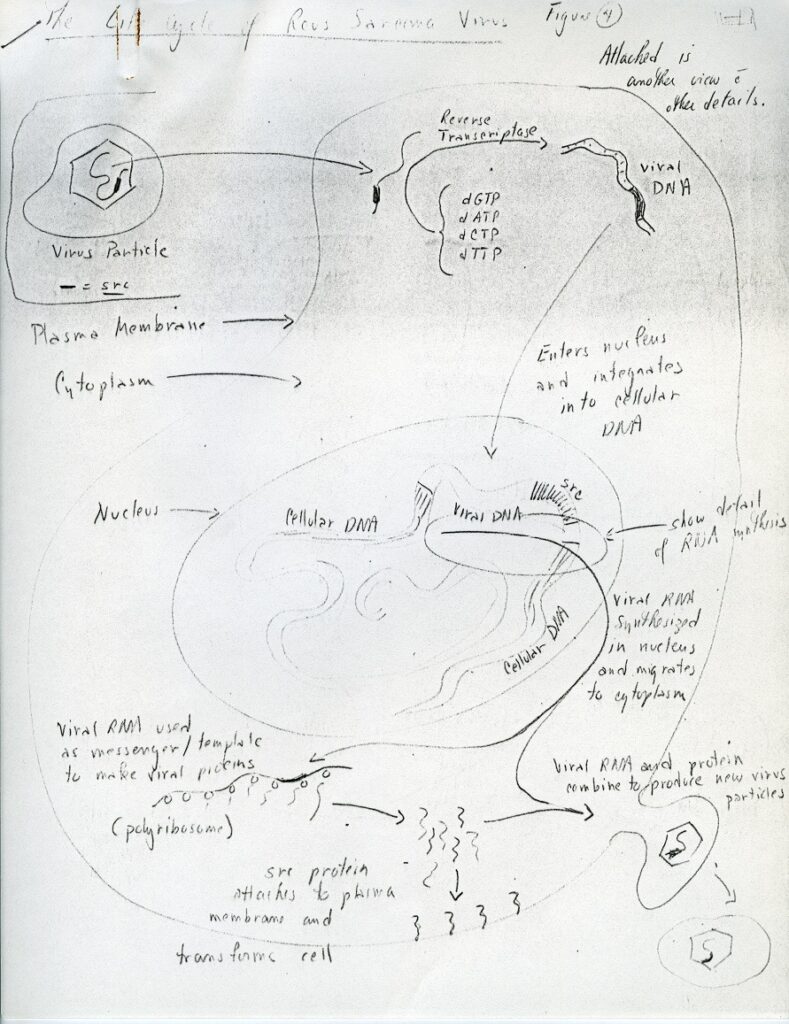

In 1989, Bishop and his research partner, Harold Varmus, were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work in cancer research. Bishop and Varmus discovered the cellular origin of retroviral oncogenes. Their work helped clarify the processes that convert normal cellular genes into cancer genes and impacted our understanding of the genesis of human cancer.

J. Michael Bishop and Harold Varmus at Nobel Shindig, a county-western themed dinner party given by Varmus and Bishop in celebration of their Nobel Prize award; held at DeMarco’s 23 Club, Brisbane, California, 1989. MSS 2007-21, carton 8, folder 41.

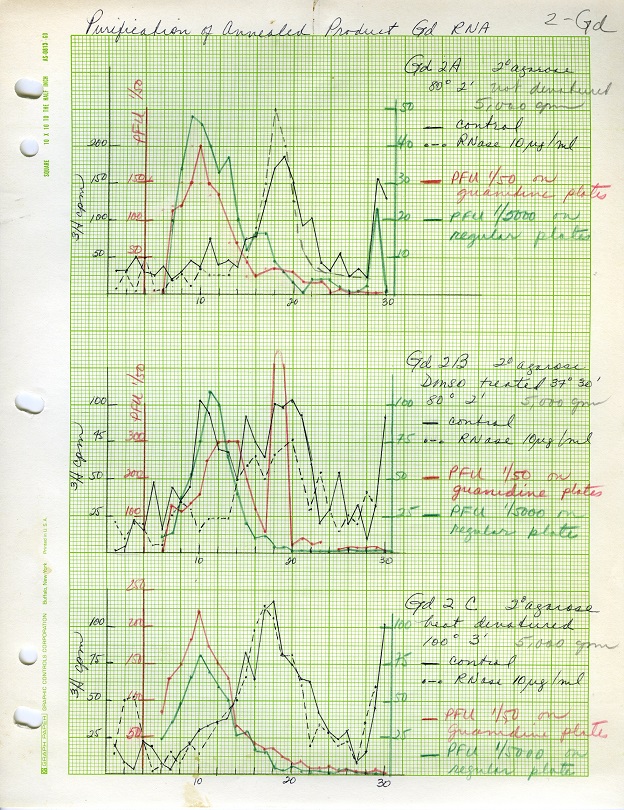

The digital collection features selections from Bishop’s laboratory research notebooks and professional papers, including article drafts, correspondence with other scientists, and teaching and lecture material. Also included are photographs and draft figures created by Bishop for his publications.

Purification of Annealed Product Gd RNA graphs. Selected page from a laboratory research binder of J. Michael Bishop, circa 1970. MSS 2007-21, carton 18, folder 3.

The Life Cycle of Rous Sarcoma Virus diagram drawing (1) by J. Michael Bishop; created for Bishop’s article “Oncogenes” published in Scientific American, 1982. MSS 2007-21, carton 2, folder 2.

You can view the digital collection on Calisphere.org. If you would like to visit the UCSF Archives and work with the complete physical collection, please check out the detailed inventory available on the Online Archive of California and make an appointment with us.