Introduction by Polina Ilieva

During the spring semester 2018 the archives team co-taught and facilitated a new History of Health Sciences course, the Anatomy of an Archive. The idea of this course was conceived by the Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine (DAHSM) Assistant Professor, Aimee Medeiros and UCSF Head of Archives & Special Collections, Polina Ilieva. Kelsi Evans, Project Archivist, co-facilitated the discussion sessions and Kelsi, Polina and David Uhlich, Access and Collections Archivist, served as mentors for students’ processing projects throughout the duration of the course.

The goal of this course was to provide an overview of archival science with an emphasis on the theory, methodology, technologies and best practices of archival research, arrangement and description. The archivists put together a list of collections requiring processing and also corresponding to students’ research interests and each student selected one that she/he worked on with her/his mentor to arrange and create a finding aid. During this 10 week long assignment students developed competence researching and describing an archival collection, as well as interpreting the historical record. At the conclusion of this course students wrote a story about their experience and collections they researched for the archives blog. In the next three weeks we will be sharing these posts with you.

Our final story comes from Hsinyi Hsieh, PhD student, UCSF Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine.

Post by Hsinyi Hsieh

Building an archival collection is similar to traveling through space and time. Before embarking on this journey, archival practitioners need to possess a diverse set of creative and sensitive abilities—specifically, a knowledge of scientific principles, a familiarity with artful practices, and the ability to think critically. Most significantly, processing a collection requires getting your hands dirty, interacting with various types of historical materials, and building a rapport with future researchers. I am grateful to have worked with Kelsi Evans and Polina Ilieva, archivists at UCSF, who not only taught me the craft of archival work through the Mary Olney collection but also provided me with a golden opportunity to travel with Dr. Olney. [1]

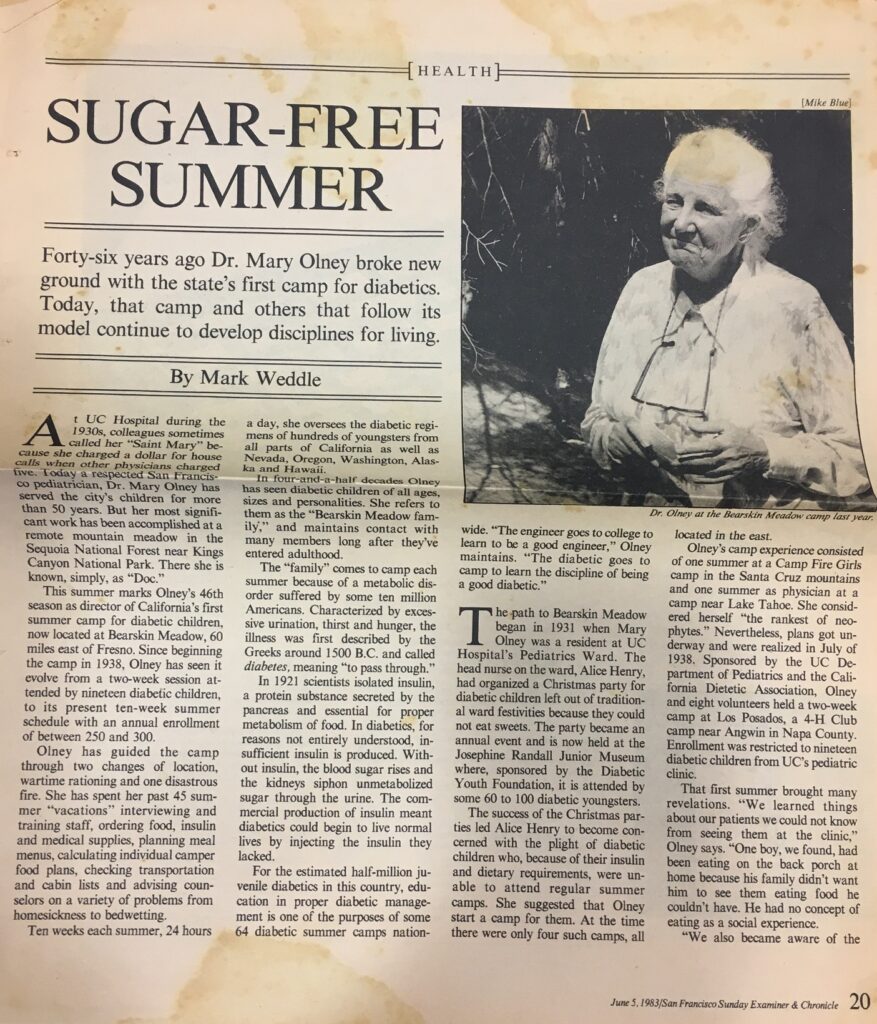

Figure 1: Mary Olney’s contribution on “Sugar Free Summer,” San Francisco Sunday Examiner & Chronicle June 5, 1983. Olney papers, MSS 98-64.

My archival journey began by imbibing tacit knowledge about processing archival collections. When we encountered some mold affected materials in the Mary Olney collection, the UCSF archivists taught me how to assess a mold bloom. It was truly a fascinating experience to watch as Kelsi and Polina observed the color and smell of the document and defined whether the mold actively presented a hazard to the unaffected materials. This document was sent for professional treatment at the UC Berkeley Library’s Conservation Treatment Division. This is an example of the tacit knowledge possessed by archivists, which only develops through continuous professional practice and education. The mold situation in the archive is akin to unforeseen circumstances arising during a trip. Thanks to the archivists’ expertise, we successfully prevented the other materials from being affected by the mold and kept our archival journey going.

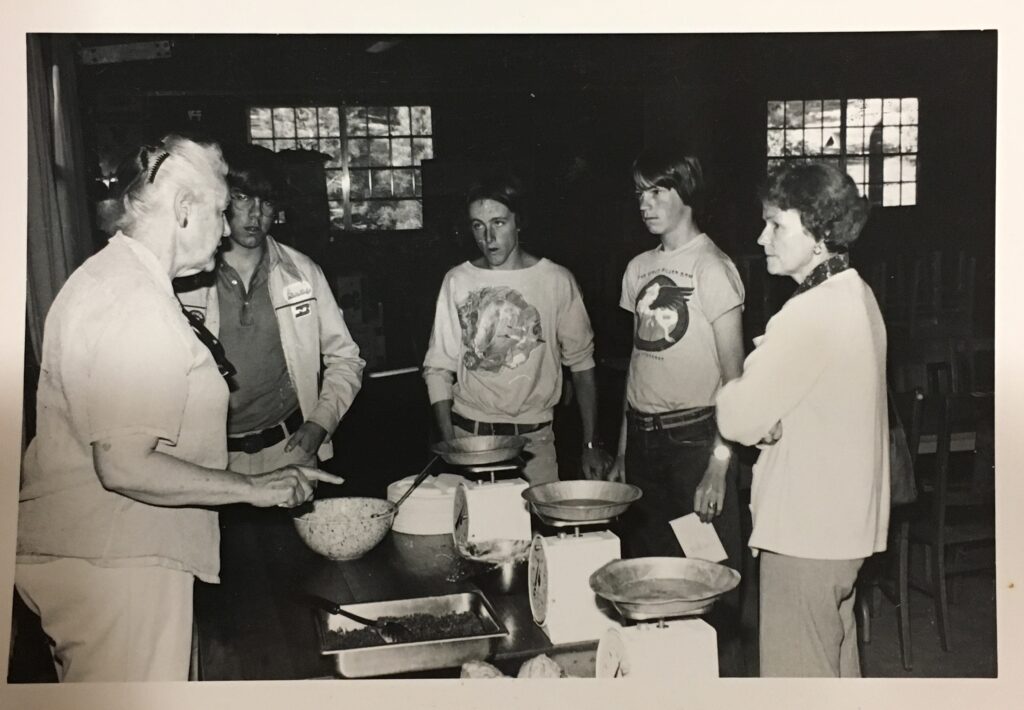

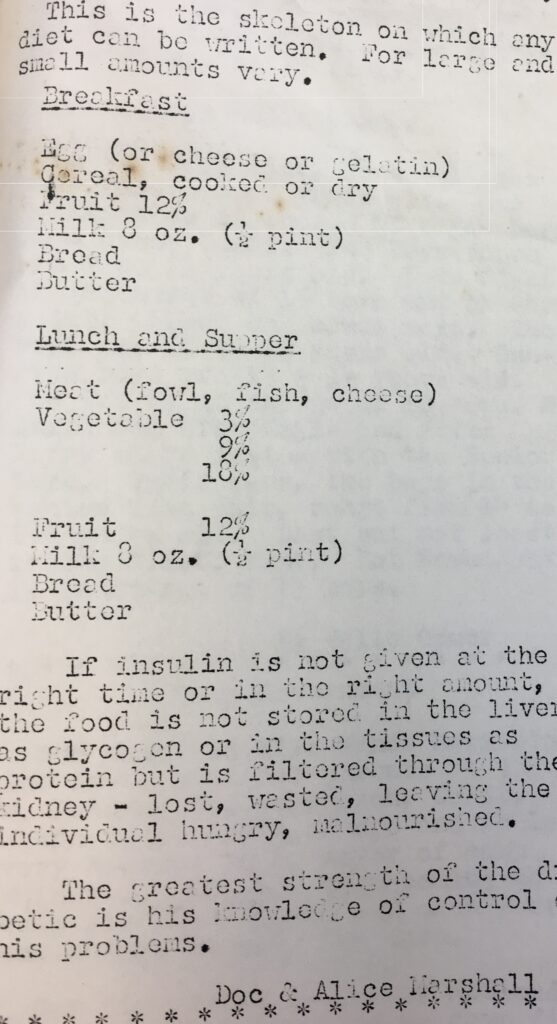

The adventure had the perfect mixture of historical lessons and archival practice. I had the opportunity to learn about Dr. Olney’s experiences as a female pediatrician, social advocate, and director of the Diabetic Youth Foundation (DYF) and its summer camps for diabetic children. As I learned more about the collection, I was able to arrange its photos, pamphlets, and correspondences for future researchers interested not only in Dr. Olney but also pediatric diabetic patients.. Through this immersive experience, I felt as though I had become a part of her camping staff but in the future. In fact, during the archival arrangement, we also reconstructed the progress of Dr. Olney’s efforts in running the summer camps for decades—notably, her hard work in terms of fundraising, staff training, and building relationships with other relevant organizations. Mary Olney was a pioneering pediatrician who not only operated under the broad vision of improving the lives of diabetic children but also employed a practical outlook, doing everything she could to maintain the summer camp for decades.

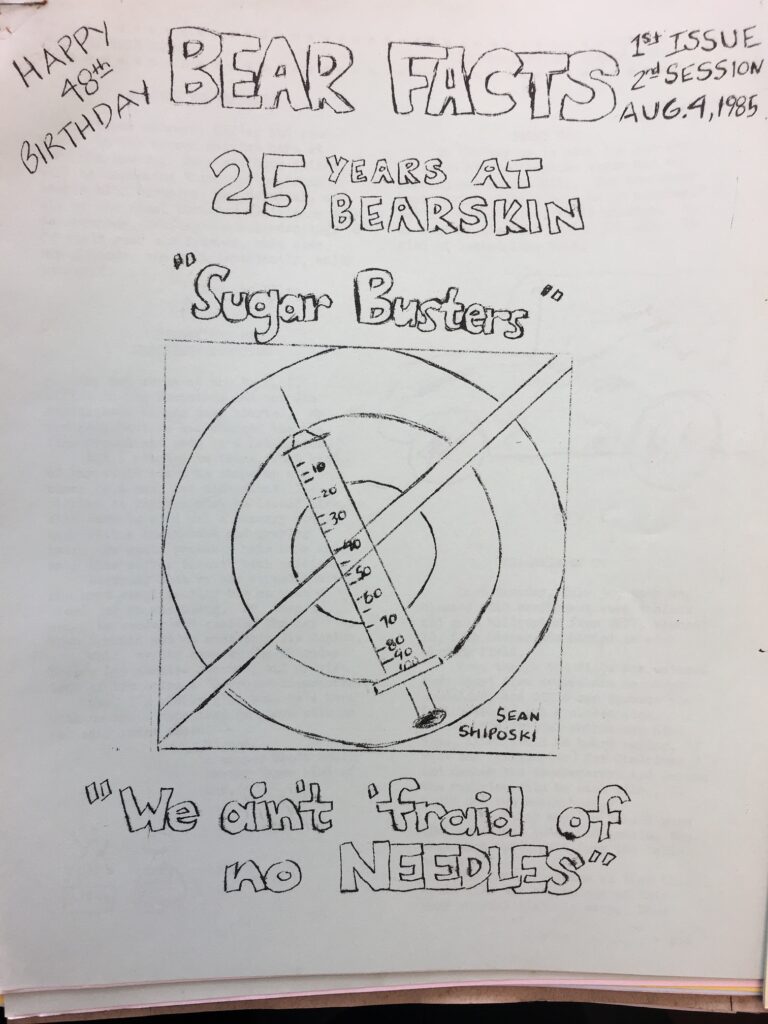

Figure 3: The cover of Bear Facts, First issue, Second session, Aug 4, 1985. Olney papers, MSS 98-64.

During archival processing, revealing the mystery of certain folders is much like exploring exotic locations while traveling. For example, I was preoccupied with examining several folders in Dr. Olney’s collection that were labeled “loose papers.” Upon examining the documents inside these folders, I found that most of the materials—specifically Bear Facts and Whitaker Whiz—were from the DYF newsletters, which aimed at improving health communication among young diabetic patients. The DYF newsletter was published since the early 1940s and targeted young patients; the newsletter introduced camping programs, provided health information about diabetes, and featured beautiful artwork and written compositions by these patients.

By relabeling these materials, “loose papers,” the archivists were able to provide researchers with more accurate finding aids and inspiration as well. Imagine that you are visiting a new country and are consulting a number of travel guides; the ones that are written more clearly might contain better suggestions on places to explore; these recommendations might be missed if you followed the relatively unclear guidebooks. Further, information that is more accurate can enable researchers to ask questions that might never occur to them otherwise. Take the DYF newsletters, for example. How do the articles in Bear Facts and Whitaker Whiz communicate medical knowledge about diet to young patients and their families? Thus, clarifying vague folder names might improve the experience of users and researchers when exploring such archives, thereby enabling them to contemplate new historical questions.

The task of processing the archival collection took me on a journey to Northern California with Dr. Olney and the DYF foundation during the twentieth century. It took me back to when and where the materials originated and how they would go on to influence researchers in the future. During her lifetime, Dr. Olney continued with her efforts to translate her expertise and knowledge into useful information for young diabetic patients. It takes the invisible labor of archivists to make these accomplishments visible and highlight all aspects of her persona: a female pediatrician, a camp organizer, a Northern California resident, a daughter, and a woman. This has been possible only through processing this archival collection. Thus, the work of archival practitioners plays a crucial role in enabling future researchers to embark on a journey with Dr. Mary Olney. Let me tell you, it is a fun and interesting ride!

[1] On the life history of Mary Olney, please see Sharon R. Kaufman, 1994. The Healer’s Tale: Transforming Medicine and Culture. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. Kelsi Evans, 2015. “Celebrating Food Day: Recipes from the Archives.” Source: https://blogs.library.ucsf.edu/broughttolight/2015/10/23/celebrating-food-day-recipes-from-the-archives/.