In this series, we’ll be exploring artifacts and other material from our collections related to medical misinformation and fraud. Step right up folks and learn how everything from bleedings to electricity can cure your ills!

Bloodletting as a medical practice has existed for thousands of years; ancient peoples, including the Greeks and Egyptians, used bloodletting to cure numerous conditions. The treatment, which involved draining blood with leeches or by puncturing the skin with a sharp instrument, was based on the theory of bodily humors. People believed that good health resulted from a balance of the four humors: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. A person suffered illness when these humors became unbalanced. Bloodletting was devised as a way to correct harmful imbalances in the body.

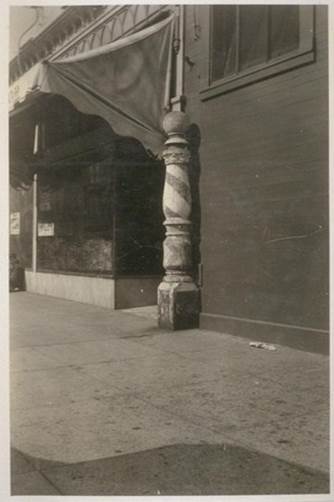

“Old wooden barber pole. 1900.” From the Graves (Roy D.) Pictorial Collection, ca. 1850-1968. Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, accessed via Calisphere: https://calisphere.org/item/ark:/13030/tf1r29n9jj

In Europe and the United States, surgeons and barbers offered bloodletting as a treatment for just about everything, from pneumonia to gout to cancer. Barbers so regularly performed bloodletting that they adopted a symbol to help advertise the service: the barber’s pole, a red and white striped pillar reminiscent of blood and bandages.

Leeches and a number of different instruments were used for bloodletting in the 18th and 19th centuries. The lancet was one of the simplest tools; it consisted of a sharp, pointed blade attached to a straight handle. A variation of this was the fleam, a wide double-edged blade at a right angle to the handle. The folding fleam pictured here includes two blades encased in a brass shield.

Folding fleam. Artifact Collection, number 431.

Folding fleam. Artifact Collection, number 431.

A spring lancet was more mechanized. It included a spring trigger that snapped the blade into a vein. Spring lancets were, perhaps unsurprisingly, difficult to clean and often became rife with bacteria.

Spring lancet and case. Artifact Collection, number 416.

Detail of spring lancet. Artifact Collection, number 416.

Scarificators allowed for multiple cuts to be made at once. The octagonal or round base housed six to twenty blades that released from the bottom with the flick of a lever.

Scarificator. Artifact Collection, number 518.

Removing scarificator from original box. Artifact Collection, number 518.

Detail of scarificator with blades extended. Artifact Collection, number 518.

Blades of scarificator. Artifact Collection, number 518.

Bleeding bowls were often used to catch blood during the procedure. These came in different sizes and material, including brass, ceramic, and pewter.

Bleeding bowl. Artifact Collection, number 557.

Today, bloodletting is widely discredited as a medical treatment. However, phlebotomy therapy is used to treat certain conditions, including hemochromatosis, a genetic disorder that causes abnormal iron accumulation. Leeches are making a comeback too; some reconstructive surgeons use them to restore circulation following procedures.

To view more bloodletting instruments, make an appointment with the UCSF Archives. You can also check out our exhibit on the third floor of the UCSF Library until April 2016. You’ll see a 19th-century spring lancet engraved to UC Medical College Dean Richard Beverly Cole from his mother!