Introduction by Polina Ilieva:

After a four-year break, last semester the archives team hosted a History of Health Sciences course, the Anatomy of an Archive. This course was developed and co-taught by the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Associate Professor, Aimee Medeiros and Associate University Librarian for Collections and UCSF Archivist, Polina Ilieva. Charlie Macquarie, Digital Archivist, facilitated the discussion on Digital Projects. Polina, Peggy Tran-Le, Research and Technical Services Managing Archivist, and Edith Escobedo, Processing Archivist, served as mentors for students’ processing projects throughout the duration of the course.

The goal of this course was to provide an overview of archival science with an emphasis on the theory, methodology, technologies and best practices of archival research, arrangement and description. The archivists put together a list of collections requiring processing and also corresponding to students’ research interests and each student selected one that they worked on with their mentor to arrange and create a finding aid. During this 11-week hybrid course students developed competencies related to researching and describing archival collections, as well as interpreting the historical record. At the conclusion of this course students wrote a story about their experiences highlighting collections they processed. In the next few weeks, we will be sharing these stories with you.

This week’s story comes from Alexzandria Simon, PhD student, UCSF Department of History & Social Sciences.

Post by Alexzandria Simon:

Having never stepped into any kind of archival space or discussion, I was excited to engage with, learn about, and understand what the archives are and mean. Now, after working with Polina Ilieva and Aimee Medeiros, at UCSF, I realize all the intricacies, time, and special attention that goes into the archival collection process. There are practices and standards that guide researchers and archivists, and emotions and ethics play a role in shaping collections and entire archives. The journey of processing a collection is time consuming, interdisciplinary, and sometimes messy. However, the craft of processing a collection allows individuals to discover new characters, information, and stories that take place during a different time and space.

When I saw my collection for the first time, all I could think to myself was how small the collection is. I was surprised after seeing others, some that consisted of 5 boxes worth of documents, that the one I was planning to work on could be confined to one file. I could not begin to comprehend how the file could tell such a large story. I began flipping through all the documents, photographs, and pamphlets and skimming through the letters and correspondence trying to put all the pieces together. The file had no organizational layout, and so my priority was to put everything in chronological order. I wanted to understand the starting point and the ending point. What I came to discover is that sometimes, collections do not always have a solid beginning and concluding aspect. Stories sometimes begin right in the middle and then end abruptly, leaving many questions.

Figure 1: “Physician – Patient – Pastor” Pamphlet, San Francisco Medical Center, May 1961, Chaplaincy Services at UCSF, MSS 22-03.

The Chaplaincy Services at UCSF Collection began with correspondence between UCSF administrators interested in starting a chaplaincy program. They sought to understand how chaplains, priests, and rabbis could have a role in their hospital space and provide services to patients. What they came to learn and understand, from informational pamphlets, is the connection between chaplains and patients is a powerful one. Chaplains offer judgement free support and a space for patient’s belief and repent needs. When a patient is alone with no family members or loved ones, they can call upon their religion to give them a person of guidance and care.

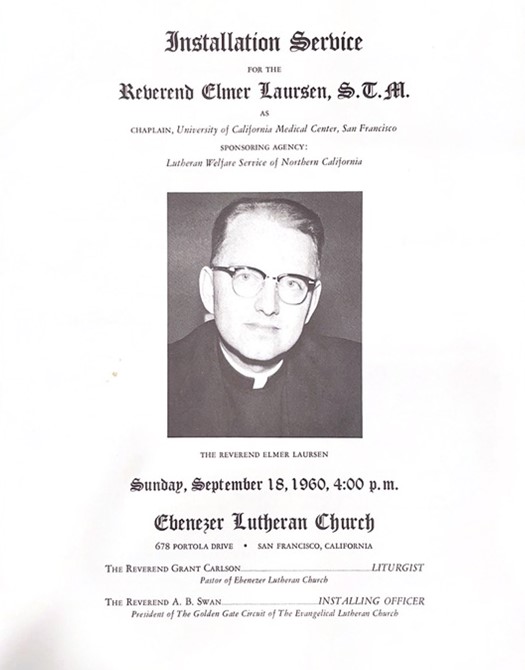

Figure 2: Installation Service Program for Reverend Elmer Laursen, S.T.M., Lutheran Welfare Service of Northern California, September 18, 1960, Chaplaincy Services at UCSF, MSS 22-03.

These discussions would ultimately lead to the establishment of a Clinical Pastoral Education Program initiated and headed by Reverend Elmer Laursen, S.T.M. Reverend Laursen was a prominent figure in the Chaplaincy Services at UCSF and established clinical pastoral work as necessary for patient care. Reverend Laursen engaged in public outreach, fundraising, patient and student advocacy, and building relationships with other colleges and hospitals. His work inspired other pastors, reverends, and religious officials to begin implementing clinical pastoral education programs to develop student learning and patient care. He believed that pastoral care is imperative to patient care. Patients deal with challenging, and sometimes traumatizing and scary, medical procedures. The Chaplaincy Program could offer solitude and peace for patients who have no one else to call on. Chaplaincy Programs offer a humanistic approach to patient care in a field that is saturated with data, clinicians, and the medical unknown.

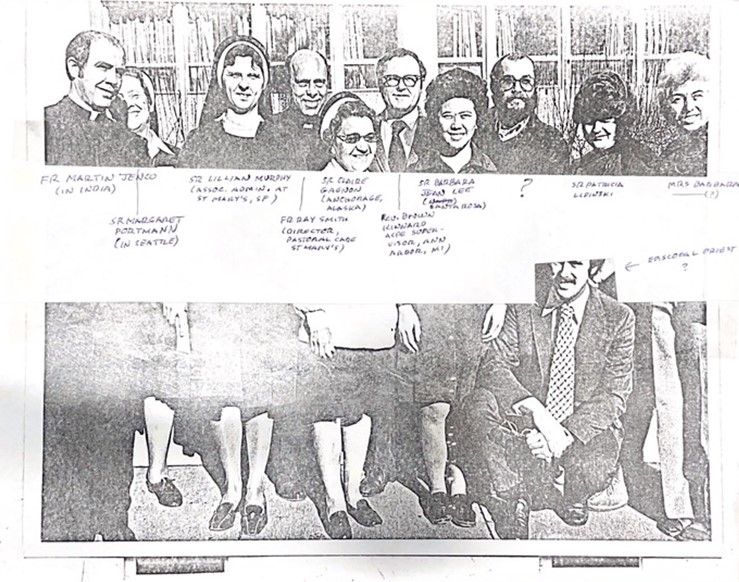

Figure 3: Group Photo of Chaplains, Reverends, Nuns, and Administrators at the 21st Anniversary Celebration of Chaplaincy Training Event, September 1982, Chaplaincy Services at UCSF, MSS 22-03.

After reading through the collection, I began dividing the documents into subject folders. These consisted of “Chaplaincy Service Materials,” “Pamphlets & Booklets,” “Funding,” “Chaplaincy Facility Space,” “Chaplain Elmer Laursen,” “Correspondence – August 1959 – September 1974,” “Photographs,” “21st Anniversary Celebration,” and “Rabbi Services.” Through these folders, the collection is now organized in a way researchers and others can trace the narrative. While I was processing the collection, I kept reminding myself to make the finding aid easy and accessible. I want anyone, scholar or not, to be able to open the finding aid or file and know what the collection includes. It is difficult to not let the records overwhelm you with tiny details. It is difficult to not get lost in every aspect of a collection. I found gaps in the correspondence, and every time I read something new, I seemed to come up with more questions. However, I believe that to be a part of the journey and work of archivists and scholars. We are always left wanting more. The documents in the collection are only a portion of the much larger story around Chaplaincy Services at UCSF. Even more miniscule in the larger history around religion and hospitals.